Jury

still out on aspirin a day to prevent heart attack and stroke

European Society of

Cardiology

The jury is still out

on whether people at moderate risk of a first heart attack or stroke should

take daily aspirin to lower their risk, according to late breaking results from

the ARRIVE study presented in a Hot Line Session at ESC Congress 2018 and

with simultaneous publication in the Lancet.

The jury is still out

on whether people at moderate risk of a first heart attack or stroke should

take daily aspirin to lower their risk, according to late breaking results from

the ARRIVE study presented in a Hot Line Session at ESC Congress 2018 and

with simultaneous publication in the Lancet.

Professor J. Michael

Gaziano, principal investigator, of the Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston,

US, said: "Aspirin did not reduce the occurrence of major cardiovascular

events in this study.

However, there were fewer events than expected, suggesting that this was in fact a low risk population. This may have been because some participants were taking medications to lower blood pressure and lipids, which protected them from disease."

However, there were fewer events than expected, suggesting that this was in fact a low risk population. This may have been because some participants were taking medications to lower blood pressure and lipids, which protected them from disease."

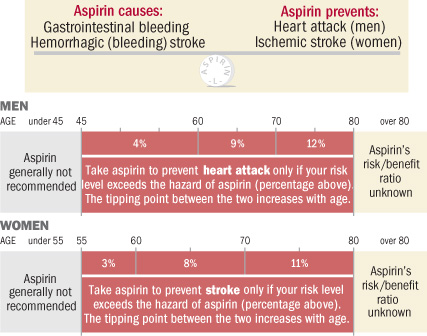

The benefit of aspirin

for preventing second events in patients with a previous heart attack or stroke

is well established. Its use for preventing first events is controversial, with

conflicting results in previous studies and recommendations for and against its

use in international guidelines.

Recommendations against its use cite the increased risk of major bleeding.

Recommendations against its use cite the increased risk of major bleeding.

The ARRIVE study assessed the impact of daily aspirin on heart attacks, strokes, and bleeding in a population at moderate risk of a first cardiovascular event. Moderate risk was defined as a 20-30% risk of a cardiovascular event in ten years.

The study enrolled individuals with no prior history of a vascular event, such as stroke or heart attack. Men were at least 55 years old and had two to four cardiovascular risk factors, while women were at least 60 years old with three or more risk factors. Risk factors included smoking, elevated lipids, and high blood pressure.

A total of 12,546

participants were enrolled from primary care settings in the UK, Poland,

Germany, Italy, Ireland, Spain, and the US. Participants were randomly

allocated to receive a 100 mg enteric-coated aspirin tablet daily or placebo.

The median follow-up was 60 months. The primary endpoint was time to first

occurrence of a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction,

unstable angina, stroke, and transient ischaemic attack.

The average age of

participants was 63.9 years and 29.7% were female. In the intention-to-treat

analysis, which examines events according to the allocated treatment, the

primary endpoint occurred in 269 (4.29%) individuals in the aspirin group

versus 281 (4.48%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR] 0.96, 95% confidence

interval [CI] 0.81-1.13, p=0.60). In the per-protocol analysis, which assesses

events only in a compliant subset of the study population, the primary endpoint

occurred in 129 (3.40%) participants of the aspirin group versus 164 (4.19%) in

the placebo group (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.64-1.02, p=0.0756).

In the per-protocol

analysis, aspirin reduced the risk of total and nonfatal myocardial infarction

(HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36-0.79, p=0.0014; HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.36-0.84, p=0.0056,

respectively). The relative risk reduction of myocardial infarction in the

aspirin group was 82.1%, and 54.3% in the 50-59 and 59-69 age groups,

respectively.

All safety analyses

were conducted according to intention-to-treat. Gastrointestinal bleedings,

which were mostly mild, occurred in 61 (0.97%) individuals in the aspirin group

versus 29 (0.46%) in the placebo group (HR 2.11, 95% CI 1.36-3.28, p=0.0007).

The overall incidence of adverse events was similar between treatment groups.

Drug-related adverse events were more frequent in the aspirin (16.75%) compared to placebo (13.54%) group (p<0.0001), the most common being indigestion, nosebleeds, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, and upper abdominal pain.

Drug-related adverse events were more frequent in the aspirin (16.75%) compared to placebo (13.54%) group (p<0.0001), the most common being indigestion, nosebleeds, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, and upper abdominal pain.

Professor Gaziano

said: "Participants who took aspirin tended to have fewer heart attacks,

particularly those aged 50-59 years, but there was no effect on stroke. As

expected, rates of gastrointestinal bleeding and some other minor bleedings

were higher in the aspirin group, but there was no difference in fatal bleeding

events between groups."

He concluded:

"The decision on whether to use aspirin for protection against

cardiovascular disease should be made in consultation with a doctor,

considering all the potential risks and benefits."