by Jesse Eisinger and Paul Kiel for ProPublica

Tax evasion is at the center of the criminal cases against two associates of the president, Paul Manafort and Michael Cohen.

Tax evasion is at the center of the criminal cases against two associates of the president, Paul Manafort and Michael Cohen.The sheer scale of their efforts to avoid paying the government has given rise to a head-scratching question: How were they able to cheat the Internal Revenue Service for so many years?

The answer, researchers and former government auditors say, is simple. The IRS pursues fewer cases of tax evasion than it did less than 10 years ago. Provided you’re not a close associate of President Donald Trump, there may never be a better time to be a tax cheat.

Last year, the IRS’s criminal division brought 795 cases in which tax fraud was the primary crime, a decline of almost a quarter since 2010. “That is a startling number,” Don Fort, the chief of criminal investigations for the IRS, acknowledged at an NYU tax conference in June.

Bringing cases against people who evade taxes on legal income is central to the revenue service’s mission.

In addition to recouping lost revenue, such cases are supposed “to influence taxpayer behavior for the hundreds of millions of American citizens filing tax returns,” Fort said. With fewer cases, experts fear, Americans will get the message that it’s all right to break the law.

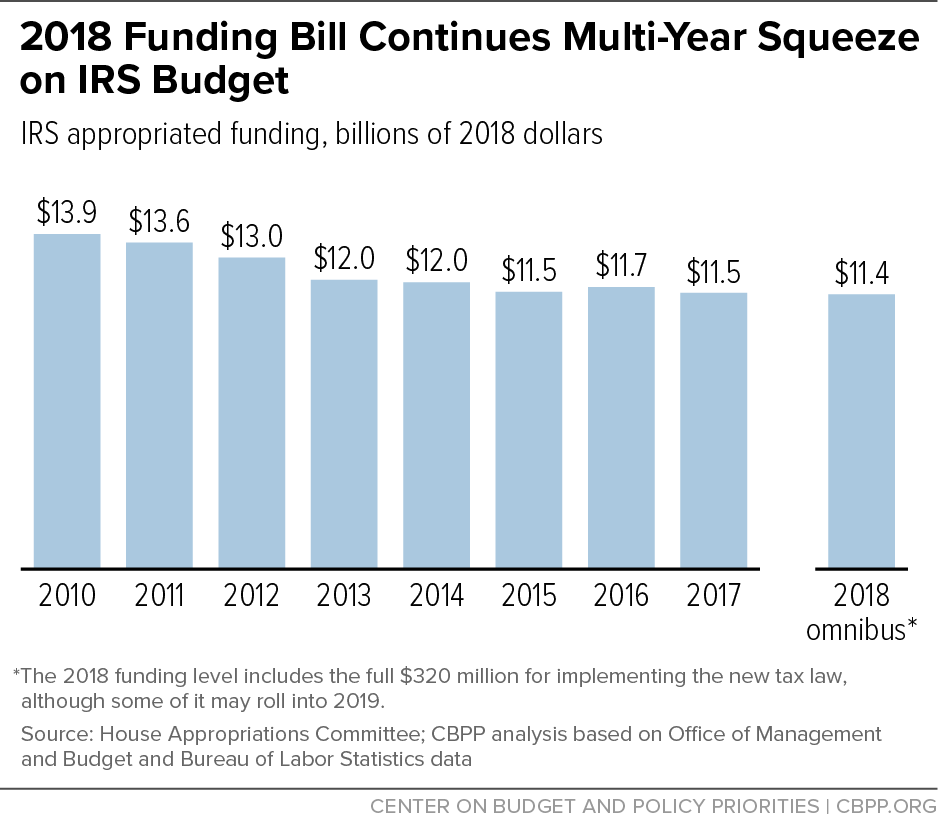

Starting in 2011, Republicans in Congress repeatedly cut the IRS’s budget, forcing the agency to reduce its enforcement staff by a third. But that drop doesn’t entirely explain the reduction in tax fraud cases.

Over time, crimes only tangentially related to taxes, such as drug trafficking and money laundering, have come to account for most of the agency’s cases.

“Due to budget cuts, attrition and a shift in focus, there’s been a collapse in the commitment to take on tax fraud,” said Chuck Pine, who used to be the third-ranking criminal enforcement officer at the IRS and is now a managing director at BDO Consulting. “I believe there are thousands of individuals who have U.S. tax obligations and are not complying with U.S. tax laws.”

The result is huge losses for the government. Business owners don’t pay $125 billion in taxes each year that they owe, according to IRS estimates.

That’s enough to finance the departments of State, Energy and Homeland Security, with NASA tossed in for good measure. Unlike wage earners who have their income separately reported to the IRS, business owners are often on the honor system.

The IRS declined to comment on its enforcement efforts.

Cohen’s and Manafort’s cases illustrate different but common types of tax cheating, and how the IRS has struggled to enforce the law. Cohen failed to report income from domestic businesses. Manafort used exotic foreign locales and shell corporations to hide his money.

Cohen’s tax evasion schemes were straightforward.

Besides paying off a pornographic movie star and a former Playboy model in violation of campaign finance laws, he pleaded guilty to lying on his tax return.

Whether it was income from his business owning taxi medallions, millions of dollars in interest payments on a loan he’d made to another taxi operator or the $30,000 he made by brokering the sale of a luxury handbag, Mr. Cohen simply hid the money from his accountant and the government. Over five years, he didn’t disclose $4.1 million, saving himself $1.5 million in taxes.

The IRS typically catches such evasion by auditing taxpayers. Theoretically, evidence picked up in audits can be used to start criminal cases.

But the rate at which the agency audits tax returns has plummeted by 42 percent since the budget cuts started. Criminal referrals were always rare and are becoming rarer still, dropping from 589 referrals in 2012 to 328 in 2016.

With the government conducting 1.2 million audits in 2016, that’s one criminal referral for roughly every 3,600 audits.

“The focus of auditors and tax collectors is not to identify fraud, it’s to collect tax,” said a special agent, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media. Management has set other priorities, he says. “So by default, the employees are not doing it.”

In addition, current and former IRS agents say that audits are not as intensive as they used to be. Because the IRS pushes agents to close audits more quickly, they make fewer requests for records and interviews.

“The quality of those referrals was also down,” said Marie Allen, a recently retired auditor who worked at the IRS for more than 30 years conducting complex financial investigations. “That is what people popularly think we should be doing, and I’m trying to say it ain’t so.”

Budget cuts have diminished the criminal investigation division, trimming the number of agents by a fifth since 2010. Recently, the IRS closed four of its 25 field offices, according to Fort. In New York state, home of the country’s financial industry, the revenue service is down to 161 agents, about a hundred fewer than it had 15 years ago.

It doesn’t help that many agents prefer chasing flashier crimes than tax evasion. Rob Warren, a research associate at Catholic University who previously spent a quarter century at the IRS, interviewed 30 former special agents. He asked each agent which of their cases had been their favorite. The answers, Warren said, typically were only tangentially related to taxes.

“It was usually narcotics, Ponzi schemes, some public corruption,” Warren said. “Agents loved Ponzi cases because there was a real victim, an old lady or something like that.”

Federal prosecutors seek out special agents for these cases because they are skilled financial investigators. And tax crimes, like failing to declare illegal income from, say, a bribe or cocaine sales, can be easier to prove than bribery or selling drugs.

In recent years, the IRS has also been pulled away from classic tax dodging cases by soaring rates of identity theft. IRS management assigned scores of agents to chase perpetrators who used stolen identities to collect tax refunds.

One tax fraud hotbed that has been a clear priority of both the IRS and the Justice Department is going after money Americans stashed overseas without reporting it to the federal government.

But there are clear reasons that Manafort, who hid his money in places like Cyprus and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, might still have escaped detection.

Switzerland has been the Justice Department’s primary target over the past 10 years, an effort that has resulted in settlements with the giant Swiss banks UBS and Credit Suisse, and dozens of smaller institutions.

The IRS allowed Americans with foreign accounts to voluntarily disclose them and pay a smaller penalty than they would have had they been caught hiding the information.

Some 56,000 people participated, netting the government $11.1 billion. The IRS’s criminal division also brought several cases against people for concealing accounts.

For all this success, there has been little change in the amount of wealth stashed overseas. Americans have about $1.2 trillion of personal assets in tax havens, according to data compiled by Gabriel Zucman, an assistant professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, and two colleagues. It’s unclear what portion has been disclosed to the IRS.

“What has happened over the last 10 years is real progress,” Zucman said. “But what the data suggest is that it has not had a dramatic effect on the amount of offshore wealth.” Money has flowed out of Switzerland and into Asian tax havens like Hong Kong and Singapore.

Moreover, the IRS has made little use of new weapons in the fight against wealth hidden overseas. In 2010, President Barack Obama signed a law that was supposed to provide a crucial tool for government auditors and prosecutors.

That law, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, required banks with American account holders to report information to the United States. Like employers filing W-2 forms about their workers, these reports would force account holders to come clean.

Eight years later, the program is still getting off the ground. Countries around the world have signed agreements, and more than 100,000 foreign banks have sent information to the United States. But “there is no ongoing compliance impact of the FATCA at this time,” according to a report this year by the inspector general for the IRS.

The report found serious problems with the millions of records collected so far. About half of the records, for example, didn’t include identification numbers for the taxpayers, making it difficult to match the accounts with specific individuals. The IRS hadn’t set up a process for using the records.

The agency said it was working on such a system.

Here, too, the cuts to the IRS’s budget have had an impact. During the Obama administration, the IRS asked Congress for hundreds of millions of dollars to carry out the program, but received nothing. Since Trump took office, the revenue service has stopped asking.