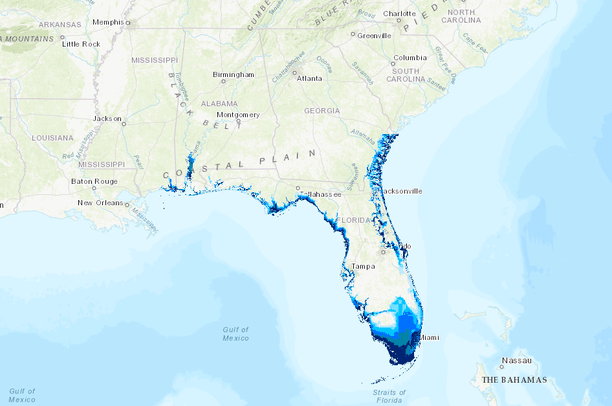

US Southeast

Atlantic coast facing high threat of sea-level rise in the next 10 years

University of Central Florida

New research shows 75 percent of the

Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Central Florida will be highly vulnerable

to erosion and inundation from rising tides by 2030, negatively impacting many

coastal species' nesting habitats.

New research shows 75 percent of the

Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Central Florida will be highly vulnerable

to erosion and inundation from rising tides by 2030, negatively impacting many

coastal species' nesting habitats.

The new data reflect a 30 percent

increase in highly vulnerable areas in the region since 2000, the date of previous

projections from the U.S. Geological Survey's Coastal Vulnerability Index.

The findings come from a study in

the The Journal of Wildlife Management, which was led by Betsy von

Holle, a biologist at the University of Central Florida.

Some of the coastal species at risk

include loggerhead and green sea turtles, threatened species that nest along

the shoreline and already face challenges such as an uptick in infectious

diseases.

According to the study, sea-level rise will increase the risk of erosion in about 50 percent of the nesting areas for those species by the next decade.

According to the study, sea-level rise will increase the risk of erosion in about 50 percent of the nesting areas for those species by the next decade.

"We need to know not only what areas are going to be the most affected by sea-level rise, but also those species most vulnerable to sea-level rise in order to figure out management plans for coastal species," von Holle says.

Seabirds don't fare any better,

according to the study. High-density seabird nesting habitat along the coast

for the gull-billed tern and the sandwich tern is expected to have

approximately 80 and 70 percent increased risk of erosion and inundation from sea

level rise by 2030, respectively.

Brown pelicans face somewhat less risk, the study showed, with only about 20 percent of their high-density nesting habitats having increased potential for inundation and erosion due to sea level rise. This is possibly because they preferentially nest in higher elevation areas, such as on artificial dredged material islands.

"We're surprised that there

were such big differences in the different species in terms of their

vulnerability to sea level rise," von Holle says.

"When there is erosion and

inundation during the reproductive seasons, it has large impacts on

species," she says. "A lot of these species that we studied are

threatened and endangered species, so just knowing that sea level rise will be

a threat to certain species in the future helps managers figure out how to

prioritize their management actions."

Although sea-level rise is a threat

to coastal species, experts say so are human-made structures, such as sea

walls, as they prevent the beach from naturally migrating inland. Without those

types of structures, the shoreline and coastal species could better adapt to

the rising seas, as they have done when faced with the threat in the past.

How they did it

To perform the study, the

researchers updated the U.S. Geological Survey's Coastal Vulnerability Index

for the South Atlantic Bight -- an area that extends from Cape Hatteras, North

Carolina, to Sebastian Inlet in Brevard County, Florida -- using updated

sea-level rise projection data from multiple sources.

The area includes the Archie Carr

National Wildlife Refuge in Brevard and Indian River counties, which is one of

the most important loggerhead nesting habitats in the world and the most

important green turtle nesting area in the U.S.

Using the updated data, the area of

the South Atlantic Bight considered to be highly vulnerable to the effects of

sea level rise increased from 45 percent in 2000 to a projected 75 percent by

2030.

The researchers then layered

existing geographical data about species' nesting density onto the

vulnerability projections to determine the overlap between coastal species

nesting locations and vulnerability to sea level rise by 2030.

They looked at habitat data for 11

coastal animals, including three sea turtle species, three shorebird species

and five seabird species.

The research was funded by the South

Atlantic Landscape Conservation Cooperative.