David Allen, Middlebury

What question are you trying to answer with your work?

What question are you trying to answer with your work?David Allen: I want to understand what drives blacklegged, or deer, ticks’ abundance and infection rate with the Lyme disease bacteria.

We broadly understand what is necessary for the tick to live in an area, but have a harder time explaining why there are such tremendous differences in tick abundance in certain locations and during certain years.

Exactly how do you measure tick abundance?

Allen: We measure it by what is called “drag cloth sampling.” We drag a 1 meter by 1 meter white cloth along the forest floor. Ticks that are searching for a host, which we call questing, will attach to the cloth as it passes over them.

At each of our plots we drag the cloth along the forest floor for 200 meters and check it every 10 meters. This is the standard way to measure tick abundance.

What spurred you to study ticks?

Allen: I grew up in Vermont in the 1980s and 1990s. During that time I do not remember ever seeing a blacklegged tick or knowing anyone with Lyme disease. When I returned to the state in 2012 to teach at Middlebury College, I would get lots of ticks when hiking. My research was spurred by this rapid and dramatic change in the tick population here.

Why is your work important to the public?

Allen: The incidence of Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases has increased dramatically in recent years. If scientists in general could better predict where ticks are the most abundant, we could target tick control strategies or at least create prevention messaging to people in those areas, and then hopefully start to decrease the rate of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.

What’s important about ticks that most people don’t know?

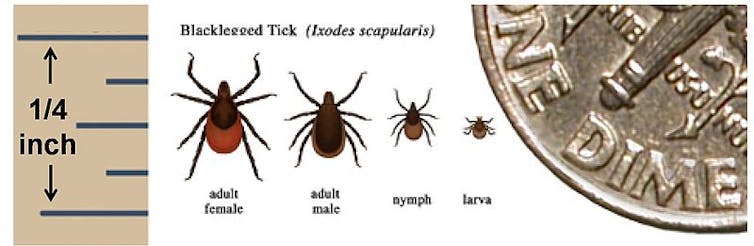

Allen: Ticks have three life stages: larva, nymph and adult. The second two life stages can transmit the Lyme disease bacteria. When most people think about ticks they picture the adult life stage. For the blacklegged tick this is about the size of a sesame seed.

I think that most people don’t have a good picture of what a nymphal tick looks like and how small it is. Nymphs are responsible for most transmission of Lyme disease to people, because they are so hard to see when they are feeding on you.

What has been the most surprising finding of your work?

Allen: I am surprised by how much tick abundance can vary across locations or years. We have found that in two sites, just three miles away from each other, one can have 20 times more ticks than the other. And then going from one year to the next, the same location can increase or decrease in abundance by four times.

What do you hope to study further?

Allen: We just started to study the small mammal community. Blacklegged ticks take a single blood meal at each life stage. During the larval and nymphal life stages, these blood meals are typically from small mammals, like mice or chipmunks.

It is from these animals that the ticks acquire the Lyme disease bacteria. My students and I have just started tracking the populations of these small mammals to better understand how they contribute to tick abundance and infection.

Any stories from the field?

Allen: We bait the small mammal traps with a mixture of oats and peanut butter. It turns out that bears find this just as tasty as the mice do. One time after setting out 100 traps, we returned the next morning to find them all thrown about. Some were dented or even pierced through with bear claw markings.

David Allen is an assistant professor in biology at Middlebury College who studies the ecology of ticks and tick-borne pathogens.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.