Delta Variant Nearly Identical to Viral Sequences Found in People

By UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania performed whole-genome sequencing of a house cat infected with coronavirus last year. The sequence, the delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, was nearly identical to those circulating in humans at the time.

Since

being identified in people in 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has gone on to infect a wide

range of animal species, wild and domestic. Concerns abound that these species

jumps could lead to novel mutations and even harmful new variants.

In a new

report, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary

Medicine and Perelman School of Medicine find that, for at least one example of

apparent interspecies transmission, crossing the species boundary did not cause

the virus to gain a significant number of mutations.

Writing

in the journal Viruses, the scientists identified a domestic house cat, treated at Penn

Vet’s Ryan Hospital, that was infected with the delta variant of SARS-CoV-2

subsequent to an exposure from its owner. The full genome sequence of the virus

was a close match to viral sequences circulating in people in the Philadelphia

region at the time.

“SARS-CoV-2 has a really incredibly wide host range,” says Elizabeth Lennon, senior author on the work, a veterinarian, and assistant professor at Penn Vet. “What this means to me is that, as SARS-CoV-2 continues to be prevalent in the human population, we need to watch what’s happening in other animal species as well.”

The find

is the first published example of the delta variant occurring in a domestic cat

in the United States. Notably, the cat’s infection was only identified by

testing its fecal matter. A nasal swab did not result in a positive test.

“This did

highlight the importance of sampling at multiple body sites,” says Lennon. “We

wouldn’t have detected this if we had just done a nasal swab.”

Lennon and

colleagues have been sampling dogs and cats for SARS-CoV-2 since early in the

pandemic. This particular pet cat, an 11-year-old female, was brought to Ryan

Veterinary Hospital in September with gastrointestinal symptoms. It had been

exposed to an owner who had COVID-19—though that

owner had been isolating from the cat for 11 days prior to its hospitalization,

another household member doing the cat care in the interim.

Working

through the Penn Center for Research on Coronaviruses and Other Emerging Pathogens

and Perelman School of Medicine microbiologist Frederic Bushman’s laboratory,

the team obtained a whole genome sequence of the cat’s virus.

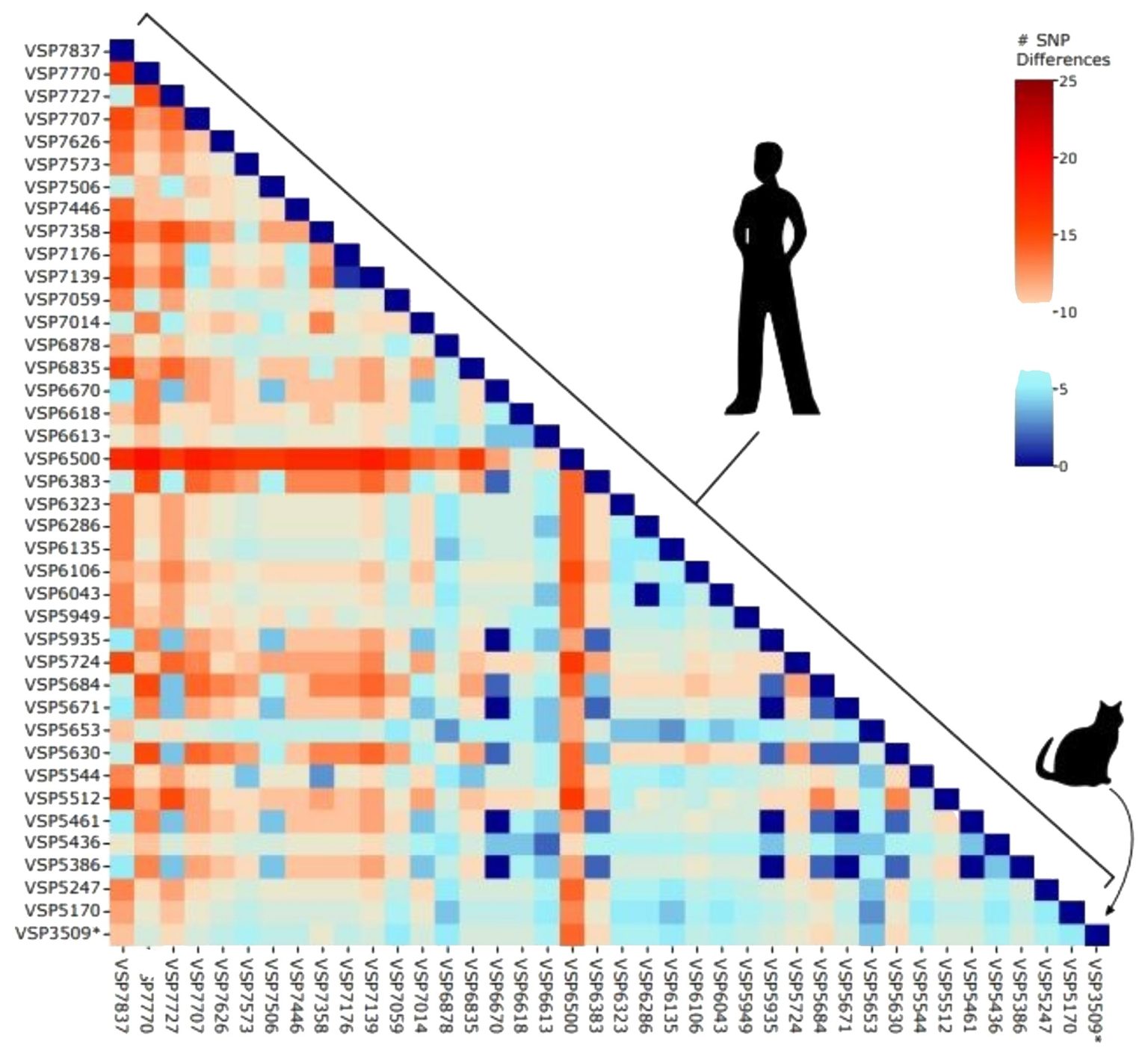

Sequencing

revealed the delta variant, more specifically, the AY.3 lineage. The

researchers did not have a sample from the infected owner. Comparing the

sequence to the database kept by the Bushman laboratory, however, the cat’s

virus was nothing out of the ordinary in terms of the sequences of SARS-CoV-2

circulating in the Delaware Valley region at the time.

“When we

looked at a random sampling of human sequences from our geographic area, there

wasn’t anything dramatically different about our cat’s sample,” Lennon says.

“So, our takeaway was that the cat was not infected by a virus that was somehow

highly different.”

Not all

variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been equally able to infect a wide range of hosts.

For example, the original Wuhan strain could not naturally infect mice; later

variants gained that ability. Scientists began seeing infections in cats and

dogs from the early days of the pandemic, presumably infected through close

contact with their owners.

“A main

takeaway here is that as different variants of SARS-CoV-2 emerge, they seem to

be retaining the ability to infect a wide range of species,” Lennon says.

While

this particular case does not raise alarms for the virus acquiring significant

numbers of mutations as it moved between species, Lennon and colleagues,

including Bushman and Susan Weiss of Penn’s medical school, hope to continue

studying other examples to see how SARS-CoV-2 evolves. Penn Vet’s Institute for

Infectious and Zoonotic Disease will facilitate this look at human-animal

interactions when it comes to pathogen transmission.

“We know

that the SARS-CoV-2 is undergoing changes as it passes between to become more

and more transmissible over time,” says Lennon. “We saw that with the omicron

variant. It’s host-adapting to people. We also want to know, when other animal

species get infected, does the virus start to adapt to those species? And for

those viruses that may adapt to a different species, do they still infect

humans?”

Reference:

“SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant (AY.3) in the Feces of a Domestic Cat” by Olivia C.

Lenz, Andrew D. Marques, Brendan J. Kelly, Kyle G. Rodino, Stephen D. Cole,

Ranawaka A. P. M. Perera, Susan R. Weiss, Frederic D. Bushman and Elizabeth M.

Lennon, 17 February 2022, Viruses.

DOI: 10.3390/v14020421

Elizabeth

Lennon is the Pamela Cole Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine at the University

of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

Lennon’s

coauthors on the study were Penn Vet’s Oliva C. Lenz and Stephen D. Cole and

the Perelman School of Medicine’s Andrew D. Marques, Brendan J. Kelly, Kyle G.

Rodino, Ranawaka A. P. M. Perera, Susan R. Weiss, and Frederic D. Bushman.

Lenz

and Marques were co-first authors and Lennon is the corresponding author.

Support

for the study came from the Penn Vet COVID-19 Research Fund, the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (grants BAA 200-2021-10986 and

75D30121C11102/000HCVL1-2021-55232), philanthropic donations to the Penn Center

for Research on Coronaviruses and Other Emerging Pathogens, and the National

Institutes of Health (grants HL137063, AI140442, and AI121485).