By TIM FAULKNER/ecoRI News staff

PROVIDENCE — There are plenty of decisions to make if Rhode Island

wants to rollback its greenhouse-gas emissions 80 percent by 2050. Planners,

however, only have until the end of 2016 to come up with a proposal. And

already one local climate-change expert claims the cuts are inadequate.

PROVIDENCE — There are plenty of decisions to make if Rhode Island

wants to rollback its greenhouse-gas emissions 80 percent by 2050. Planners,

however, only have until the end of 2016 to come up with a proposal. And

already one local climate-change expert claims the cuts are inadequate.

Brown University professor J. Timmons Roberts said the proposal

before the state Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Commission “must include far

more ambitious scenarios and models for emission reductions.” Specifically,

Roberts believes the state should seek zero net emissions by 2050, or sooner if

technologies to store carbon aren’t deployed.

Roberts who attended the recent COP21 United Nations climate

summit in Paris, serves on the Science and Technology Advisory Board, one of

two subcommittees of the state Executive Climate Change

Coordinating Council (EC4).

Roberts said the global goal of keeping temperature below a 1.5-degree Celsius increase requires “all-out action to reduce emissions.” Due in large part to manmade emissions, global temperatures have already increased about 0.75 degrees since 1880, according to NASA. Other scientific organizations suggest that the 1-degree threshold may be reached in 2016.

Some of the groundwork for a state emission-reduction plan began

Dec. 15 at the first public meeting of a greenhouse reduction advisory board,

which is the second EC4 subcommittee.

The team of energy-policy experts soon learned that simply

measuring emissions is challenging. The meeting’s lengthiest discussion focused

on a debate about a consumption-based or a generation-based emissions model.

The consumption model measures carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that

are released by say driving or heating a home. The generation model looks at

all emissions created within the state. This includes power plants whose

electricity is consumed in and out of state.

Power-plant emissions present a challenge because electricity

generation tripled in Rhode Island between 1990 and 2010. In 1990, the state

imported most of its electricity. After the construction of two major power

plants, Rhode Island now generates more electricity than it uses and exports

excess energy to the New England power grid.

The geographic boundary of climate emissions is another gray area.

Emissions from fracking of natural gas in Pennsylvania and Ohio and used by

local power plants won’t be included in the emission count. But the plan will

account for emissions leaked during transmission and distribution of natural

gas within Rhode Island.

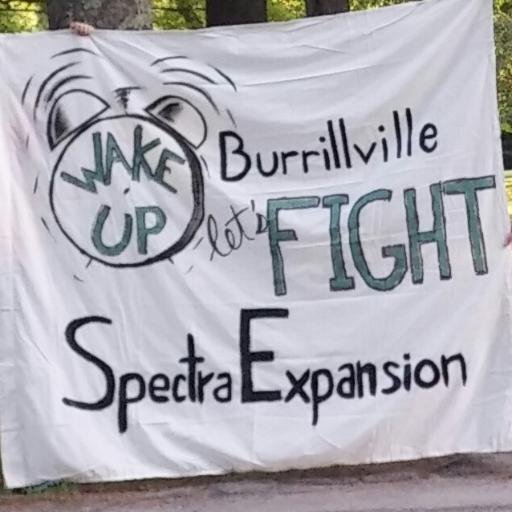

The proposed 900-megawatt Clear River Energy Center in

Burrillville will be accounted for in the plan. However, the merits of the

natural-gas power plant won’t be considered. Initially, the social and health

costs of emissions won’t be included. Emission-reduction policies such as a

carbon tax will be studied.

Some of the suggested methods for cutting emissions include

expanding electric-vehicle use; increased electric heating and reducing climate

emissions from the power grid.

Possible solutions also include boosting the

state’s energy-efficiency programs, cleaner waste management, renewable-energy

incentives and expanding greenhouse gas sinks, such as forests, that store

carbon dioxide emissions.

Possible emission-reduction policies include transit-oriented

development, caps on airport and seaport emissions, and biofuel incentives.

“When you talk about an 80 percent reduction everything is on the

table. There is no single sector alone that’s going resolve that level of

reduction,” said Paul Miller, a consultant with Boston-based Northeast States

for Coordinated Air Use Management (NESCAUM), one of the organizations

facilitating the plan.

Fiscal costs and policies that require legislation also will be

analyzed. The final plan must be approved by the EC4 and submitted to Gov. Gina

Raimondo by Dec. 31, 2016.

Miller noted that the planning in 2016 should be aspirational and

not get stymied by fears that policies will meet political resistance.

“Some of this stuff is going to be harder to do than others,” he

said. “It’s just the nature of something this big.”

After the global climate agreement in Paris, Rhode Island must do

its part to advance climate mitigation along with its neighboring states,

Miller said. Massachusetts and Connecticut have similar greenhouse

gas-reduction targets.

“Rhode Island alone is not going to solve the problem,” Miller

said.

NESCAUM, it’s worth noting, is a nonprofit

consortium of state air-quality directors from New England, New York and New

Jersey. The group consults on climate-change and air-pollution planning.

In 1990, Rhode Island generated 10.74 million metric tons of

carbon dioxide. In 2010, the state generated 12.25 million metric tons. The top

three emitters in 1990 were highway vehicles (41 percent), residential heating

(22 percent) and commercial heating (7 percent). In 2010, the top three

greenhouse-gas emitters were highway vehicles (30 percent), electric power

generation (26 percent) and residential heating (19 percent).

The greenhouse-reduction mandate was established in 2014 by the General

Assembly. The emission-reduction targets include a 10 percent cut by 2020 and a

45 percent cut by 2035.

The 17-member Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Commission is

scheduled to meet next Feb. 23. Members of the committee represent National

Grid, Brown University, renewable-energy policy groups, Rhode Island Public

Transit Authority, Providence and South Kingstown, Oil Heat Institute of Rhode

Island, Public Utilities Commission, and private sector and commercial groups.