At

home or in the wild, even fastidious conservationists can forget about cleaning

up after the things they can't see.

I just got back from hiking 95 miles in the Sierras. (Yes, just

like that Reese Witherspoon movie Wild, only far fewer miles.)

I just got back from hiking 95 miles in the Sierras. (Yes, just

like that Reese Witherspoon movie Wild, only far fewer miles.)

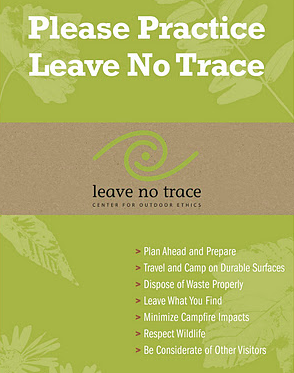

I returned from my trip with something eating at me. Backpackers

are supposed to “Leave No Trace.” It’s not just a nice concept, but a specific

set of rules we follow — even when we go to the bathroom.

You dig a hole at least six inches deep before doing your

business, and you bury it. And you do that far enough away from lakes and

streams to prevent contamination of the water we all drink.

You’re even supposed to take your used toilet paper with you

when you leave, because nobody wants to feel like they’re hiking in a

bathroom. Obviously, you clean up and pack out your trash, too.

Serious hikers are fastidious about doing those things. Some go

so far as to hide evidence of their campsites before leaving by scattering

twigs and stones over the spot where their tent was.

And it’s not uncommon at all for hikers and backpackers to police one another. Don’t ever tell anyone else you didn’t pack out your used toilet paper unless you want to catch hell for it.

But Leave No Trace seems to extend only to the easily visible:

trash, toilet paper, bodily functions, and so forth. Anything you can’t see

with the naked eye — like sweat, detergent, sunblock, mosquito repellent,

pesticides, and other chemicals — seems to get a pass.

Again and again, I saw hikers bathing and doing their laundry

and even washing dishes in lakes and streams. And this is the water that we all

drink.

Sure, we filter it, boil it, or chemically treat it before drinking it.

But those methods are designed to kill off microbes, not to remove the

chemicals in consumer products.

What’s more, all of the plants and animals rely on that water

too. The insects, which provide food for birds, reptiles, and other animals,

need that water. The trout, that hikers like to catch and eat, live in it.

I want to eat trout with butter and lemon as seasoning, not with

pesticides and detergent.

Many conscientious backpackers at least go to the trouble of

packing biodegradable soap. But your clothes carry residue of your laundry

detergent from home, as well as your sweat.

Some treat their clothing with

pesticides to help with the mosquitoes. Others treat gear with waterproofing

chemicals.

Then, of course, everyone slathers bug spray and sunblock all

over themselves.

The bugs were bad this time, and the sun is intense at high

altitudes. I understand using those chemicals. But don’t rinse them off in the

stream.

The alternative to bathing and washing in the stream is only

slightly more work. You gather some water, haul it a few hundred feet, and use

it to do your washing where it won’t contaminate an entire river.

The reason why I share this, presumably with many who will never

backpack in their lives, is because it seems to reveal a more general truth

about humanity: We underestimate or ignore what we cannot easily see.

Between the chemicals rinsed off in the streams and the toilet

paper so carefully packed out, the chemicals harm the environment more. But

it’s the toilet paper, which we can see, that gets the attention.

Back in the “real world,” with trash service and running water

and flush toilets, our interactions with the environment are easier to ignore.

Here, we never have to worry that going to the bathroom in the wrong place

could result in contaminated drinking water.

But whether in the wilderness or in the city, it’s dangerous and

harmful to discount the impact of what we can’t see, just because we can’t see

it.

OtherWords

columnist Jill Richardson is the author of Recipe for America: Why Our

Food System Is Broken and What We Can Do to Fix It. OtherWords.org.