Trump and the Reverse

Revolving Door

Late in his

presidential campaign Donald Trump seized on the issue of government ethics,

and since the election he has talked about putting stricter limits on

the ability of federal officials to move into jobs with government contractors.

That process, called the revolving door, creates the possibility that an

official will skew decisions in favor of a future employer.

Late in his

presidential campaign Donald Trump seized on the issue of government ethics,

and since the election he has talked about putting stricter limits on

the ability of federal officials to move into jobs with government contractors.

That process, called the revolving door, creates the possibility that an

official will skew decisions in favor of a future employer.

What Trump has not

discussed is a related phenomenon that can also have a pernicious effect on

federal policymaking: the appointment of lobbyists and corporate executives to

public posts in which they are likely to pursue policy in a way that benefits

their former (and probably future) employers and business interests. This is

known as the reverse revolving door.

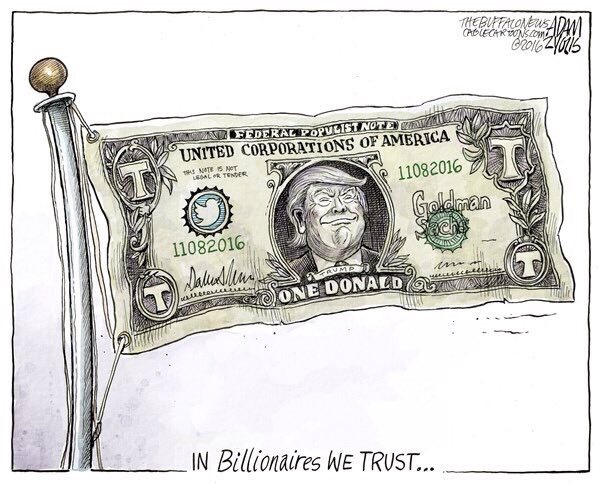

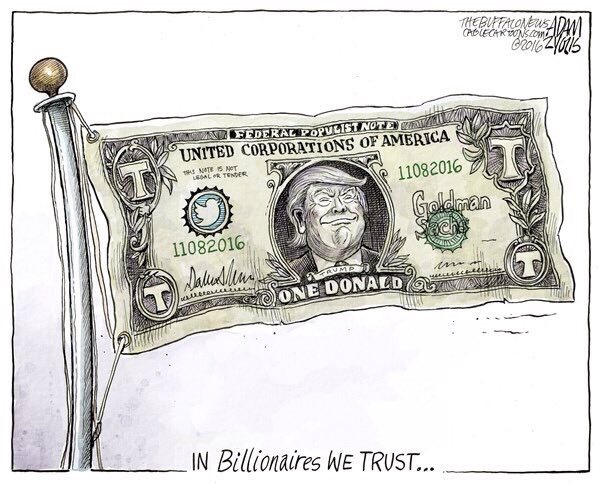

Not only has Trump not

challenged that practice, he has embraced it with gusto — and personally

embodies it.

Along with retired generals and conservative zealots, his proposed cabinet includes hedge fund investor Steve Mnuchin as Treasury Secretary, vulture investor Wilbur Ross as Commerce Secretary and fast food executive Andy Puzder as Labor Secretary.

And now comes the coup de grace: the nomination of ExxonMobil chief executive Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State.

Along with retired generals and conservative zealots, his proposed cabinet includes hedge fund investor Steve Mnuchin as Treasury Secretary, vulture investor Wilbur Ross as Commerce Secretary and fast food executive Andy Puzder as Labor Secretary.

And now comes the coup de grace: the nomination of ExxonMobil chief executive Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State.

Despite claims that

Trump is breaking all the rules, his decision to include prominent private

sector figures in his cabinet is far from novel.

Despite claims that

Trump is breaking all the rules, his decision to include prominent private

sector figures in his cabinet is far from novel. There are ample precedents for such an approach, especially but not exclusively in Republican administrations.

The pattern has been

most pronounced with the Treasury Secretary.

Over the past 60 years, that post has frequently been awarded to members of the financial and corporate elite.

Eisenhower, for example, gave the job to George Humphrey of the steel company M.A. Hanna. Kennedy chose C. Douglas Dillon, who had been with the Wall Street firm Dillon, Read. Carter tapped W. Michael Blumenthal, who had headed the manufacturer Bendix International.

Over the past 60 years, that post has frequently been awarded to members of the financial and corporate elite.

Eisenhower, for example, gave the job to George Humphrey of the steel company M.A. Hanna. Kennedy chose C. Douglas Dillon, who had been with the Wall Street firm Dillon, Read. Carter tapped W. Michael Blumenthal, who had headed the manufacturer Bendix International.

Clinton’s second

Treasury Secretary was Robert Rubin of Goldman Sachs. Reagan’s first Treasury

Secretary was Donald Regan, head of Merrill Lynch. George W. Bush turned to the

corporate sector three times, choosing Paul O’Neill of Alcoa, John Snow of CSX

and Henry Paulson of Goldman Sachs. Obama’s second Treasury Secretary was Jack

Lew, who had worked at Citigroup.

While Trump has picked

a retired general to run the Pentagon (a separate problem), the position of

Secretary of Defense is another top cabinet post that has often been filled by

corporate figures.

Eisenhower’s choice was Charles E. Wilson, the former General Motors president who in his confirmation hearing famously said: “For years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist.”

Kennedy tapped Robert McNamara, who had just been named president of the Ford Motor Co. Reagan’s first Defense Secretary was Caspar Weinberger, who had joined the engineering giant Bechtel Corp. a few years earlier after a career in the public sector. George W. Bush chose Donald Rumsfeld, who had stints as chief executive of G.D. Searle and later General Instrument.

Eisenhower’s choice was Charles E. Wilson, the former General Motors president who in his confirmation hearing famously said: “For years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist.”

Kennedy tapped Robert McNamara, who had just been named president of the Ford Motor Co. Reagan’s first Defense Secretary was Caspar Weinberger, who had joined the engineering giant Bechtel Corp. a few years earlier after a career in the public sector. George W. Bush chose Donald Rumsfeld, who had stints as chief executive of G.D. Searle and later General Instrument.

Looking at cabinets as

a whole, it was during the Reagan Administration that an overall business

presence first became quite pronounced.

In addition to Regan and Weinberger, the corporate veterans in Reagan’s cabinet included Secretary of State Alexander Haig, who had become president of United Technologies after his military career.

After Haig resigned in 1982, Reagan replaced him with George Shultz, who had headed Bechtel Corp. during the 1970s. Commerce Secretary Malcolm Baldridge had been chairman of Scovill Inc. Even the Secretary of Labor, Raymond Donovan, had a business background as an executive at a New Jersey construction company.

In addition to Regan and Weinberger, the corporate veterans in Reagan’s cabinet included Secretary of State Alexander Haig, who had become president of United Technologies after his military career.

After Haig resigned in 1982, Reagan replaced him with George Shultz, who had headed Bechtel Corp. during the 1970s. Commerce Secretary Malcolm Baldridge had been chairman of Scovill Inc. Even the Secretary of Labor, Raymond Donovan, had a business background as an executive at a New Jersey construction company.

This pattern was

repeated in 2001. The elevation of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney to the two

highest posts in the land could itself be seen as a significant case of the

reverse revolving door.

Bush, after all, spent much of his career as a businessman in the oil & gas industry and then as a part-owner of the Texas Rangers baseball team. Bush had not risen to great heights in the corporate world before running for governor of Texas, but he had clearly been shaped by that world.

Cheney had spent five years as the chief executive of the controversial Halliburton Co.

Bush, after all, spent much of his career as a businessman in the oil & gas industry and then as a part-owner of the Texas Rangers baseball team. Bush had not risen to great heights in the corporate world before running for governor of Texas, but he had clearly been shaped by that world.

Cheney had spent five years as the chief executive of the controversial Halliburton Co.

Bush chose as his

chief of staff Andrew Card, who had been a vice president of General Motors and

a lobbyist for the auto industry. In addition to selecting Alcoa CEO Paul

O’Neill to head Treasury and one-time corporate executive Donald Rumsfeld to

run Defense, Bush chose oil executive Donald Evans as Secretary of Commerce and

Anthony Principi, an executive with a medical services company, to be Secretary

of Veterans Affairs.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice had not been a

corporate executive but was on the board of Chevron, which had named an oil

tanker after her (left).

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice had not been a

corporate executive but was on the board of Chevron, which had named an oil

tanker after her (left).

Trump’s corporate

cabinet picks may be in keeping with some past practices, but they are

troubling nonetheless. As with Reagan and Bush II, the nominations are clearly

intended to foster an attack on regulation and the promotion of

corporate-friendly policies.

With Tillerson there

an even bigger issue. The main problem with reverse revolving door appointments

is the danger of conflicts between the interests of a particular corporation

and the public interest on specific issues. A corporation of the size and

influence of Exxon Mobil is not just another company — it is in effect a state

unto itself.

Trump praises

Tillerson for the extent of his dealings with foreign leaders. Yet he did not

develop those relationships representing the interests of the United States.

Exxon Mobil has its own foreign policy that has frequently gone in different

directions than that of the country in which it is nominally base.

Much attention is

being focused on Tillerson’s dealings with Russia, which are indeed disturbing.

Yet those dealings are just one example of how Exxon Mobil pursues its business

interests without regard to other considerations such as human rights — an

issue in the U.S. Secretary of State is supposed to champion.

In the 1950s GM’s

Charlie Wilson could get away with identifying the interests of his company

with those of the country as a whole. Tillerson cannot do the same.

Note: This report

draws on a chapter I wrote for a 2005 report published by the Revolving Door

Working Group.