Some 60 acres of forest in

Johnston, R.I., were bulldozed this year to make room for a 420,000-square-foot

office park. The Johnston Land Trust was mum on the subject. (Frank

Carini/ecoRI News)

Rhode Island’s splintered collection of land trusts and

environmental organizations accomplish many things, but much of this important

work is conducted in isolation. Intentionally or not, the state’s tangle of

conservation projects are done in small groups. The collective voice of this

movement is a whisper when Rhode Island needs a scream.

There’s no true unified front, statewide or even regionally, to

adequately confront the constant development threats to the Ocean State’s

collection of wetlands, salt marshes and open space.

The state is flush with understaffed and underfunded environmental

nonprofits competing, often against each other, for the same pot of dwindling

gold. It’s likely that with so many organizations going it alone, their

collective message is diluted and their work, duplicated.

There’s more power in unity, especially when it comes to pushing

back against politically supported corporate projects that shove aside public

concern and end up diminishing the local landscape, stressing water resources

and jeopardizing public health. It’s a pattern of abuse Rhode Island can’t seem

to shake.

“Rhode Island continues to lose forest and soil, and our water resources are continuously threatened,” said Providence resident Greg Gerritt, an environmental advocate and founder of the think tank Prosperity for Rhode Island. “We’re in the Age of Stressed Environments.”

Natural resources need time to heal, but in a state where job

creation and "cranes in the sky" is the directive from leadership,

there's little opportunity. Consequently, open space becomes more fragmented.

Increasing amounts of sewage and wastewater, and the chemicals used in

treatment, diminish the health of Narragansett Bay. The state’s growing expanse

of impervious surfaces rush a tidal wave of pesticides, fertilizers, motor oil,

antifreeze and debris into local waterbodies.

The state’s collection of environmental organizations and land

trusts, made up mostly of volunteers and low-paid staff, can’t compete with the compromises the

state continually makes to increase unimaginative development that further

erodes important natural resources.

As things currently stand, protecting the quality and quantity of

Rhode Island’s dwindling open space requires concerned residents sacrificing

time from work and family to sit through council, planning board and zoning

meetings.

It requires filling out requests for public information, which are

often ignored. It requires advocates and residents spending time at the

Statehouse, attending hearings and testifying. It requires being arrested for

chaining oneself to construction equipment.

It means writing e-mails to local

representatives. It requires making signs and organizing protests and sit-ins.

It means getting signatures and filing petitions. It takes blood, sweat and

tears. And, of course, it requires money.

Developing open space just takes money. Everyone involved is

getting paid.

The governor and Statehouse power brokers speak at chamber of

commerce events. They meet with developers, investors and trade unions.

Meanwhile, environmentalists are left to beg and plead for what eventually

become watered-down protections that are largely ignored, like the many

taxpayer-funded studies and comprehensive plans to better manage Rhode Island’s

land-use practices.

The governor and the power brokers mostly decline

invitations to meet with environmental groups. They rarely make time to speak

with protestors and advocates.

“Volunteerism drives environmentalism and it would be nice if the state supported these organizations,” Art Ganz, president of the Salt Ponds Coalition, told ecoRI News during a recent interview at the Kettle Pond Visitor Center in Charlestown. “Instead, the state cuts funding and local endeavors are lost.”

For example, during the 2016 General Assembly session, lawmakers

defunded a state-mandated conservation organization. The Rhode Island State

Conservation Committee was established by state law in 1944 to help meet the

needs of local land users for the conservation of land and water.

By cutting funding to Rhode Island’s three conservation districts,

the state will save about $36,000 annually.

The Legislature also refused to support the governor’s budget

request for two additional staffers to help address environmental enforcement

capacity at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

“The challenge is how do we start managing land to get to the

things we want and a healthier landscape,” Carol Lynn Trocki, a Rhode Island

Land Trust Council board member, recently told ecoRI News over coffee at a

popular Little Compton shop.

Fragmented approach

During the seven-plus years ecoRI News has been covering

environmental issues in southern New England, we have heard from many people,

both affiliated and unaffiliated with Rhode Island environmental nonprofits,

who believe well-intentioned environmental organizations don’t — for reasons

both complex and silly — typically work in concert.

This go-at-it-alone mentality essentially creates a piecemeal

approach to conservation that feeds the state’s lack of environmental vision.

It’s also no match for Rhode Island’s economic development policy, which some,

such as Gerritt, call “misguided” and say “mistakes real-estate speculation as

economic development.”

Rhode Island’s reliance on real-estate development to grow the

economy produces parking lots, office parks, big-box stores, casinos,

travel plazas, truck stops and fossil-fuel power plants. Woodlands, wetlands

and watersheds are sacrificed for this “progress.”

Costs related to the loss of

ecosystems are ignored, or never even considered. Beach closures, loss of

habitat, flooding and lack of diversity are the byproducts of this shortsighted

approach.

The state’s collection of terrific scientific talent, passionate

environmental organizations and dedicated volunteers — combined with some

strong environmental regulations — helps maintain a semblance of balance. But,

as Ganz noted, “so much damage has already been done.”

Planting trees in Rhode Island’s urban core is important work to

combat the heat-island effect and improve public health, but those efforts need

to be matched when it comes to better protecting the state’s existing

woodlands, even if they are all second-growth forests. We can’t afford to keep

clearing forestland.

“Better ecological protection is the future of our economy. We’re

just scratching the surface when it comes to greening the economy,” Gerritt

said. “We all like to go to the water, but there’s no water access without land

conservation. What makes Rhode Island livable is activism.”

Imagine what the state’s collection of environmental

organizations, land trusts and volunteers could accomplish if their work and

efforts were better coordinated.

The dominant forest of

Weetamoo Woods in Tiverton is coastal oak-holly. The preserved property also

features an Atlantic white cedar swamp. (Joanna Detz/ecoRI News)

Land conservation

The diversity of Rhode Island’s open space provides both residents

and visitors with cultural, natural and recreational opportunities. These areas

also help control erosion, clean the air and purify the water.

About 22 percent, some 57 square miles, of Rhode Island’s 1,212

square miles has been permanently protected from development. However, some 60

percent of the state is undeveloped and unprotected, according to an op-ed written last

year by DEM staffer Scott Millar, who noted that land development was

increasing at a pace that was nine times faster than Rhode Island’s population

growth.

“Many of our most important farms, drinking water supplies and

habitat are on lands that can be developed at any time, placing these critical

resources at risk,” Millar wrote. “In the past, unplanned growth has led to the

loss of our working farms and forests, impaired water quality and destroyed

habitat.”

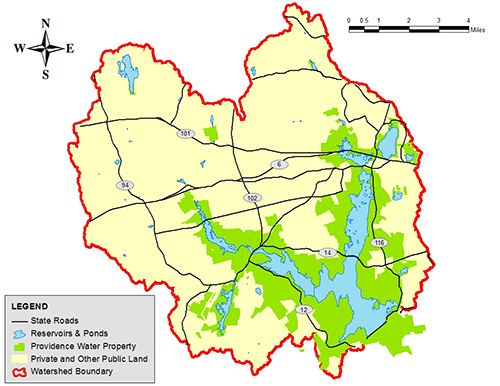

The 13,000 acres of land,

highlighted in lime green above, that surround the Scituate Reservoir aren’t

protected from development should Providence Water want to sell its property.

(Providence Water)

The 13,000 acres of land,

highlighted in lime green above, that surround the Scituate Reservoir aren’t

protected from development should Providence Water want to sell its property.

(Providence Water)

Among the areas not protected are the 13,000 acres Providence

Water owns around the Scituate Reservoir, which provides drinking

water to 60 percent of the state.

“Providence Water could sell that land to a developer or a private

water supplier that would then have all this waterfront property on the

reservoir,” Rupert Friday, executive director of the Rhode

Island Land Trust Council, recently told ecoRI News. “There’s

nothing keeping that land from being developed or sold to a developer.”

Friday also noted that future development looms over other parcels

of land that many Rhode Islanders likely assume are already protected, such as

the 1,800-acre Yawgoog Scout Reservation in Rockville; the University of Rhode

Island’s W. Alton Jones Campus and its 2,300 acres of forests, lakes and farmland

in West Greenwich; and Brown University’s 372-acre Haffenreffer property in

Bristol.

The assault on the state’s open space began in the 1940s. Since

then, Rhode Island has lost 80 percent of its farmland, according to Friday.

Rhode Island’s first land trusts — the Sakonnet Preservation

Association and the Block Island Conservancy — were created 44 years ago, three

decades after much of the state’s farmland was lost to subdivisions and

cul-de-sacs. Rhode Island’s current collection of 48 land trusts has been playing catch up

ever since, protecting nearly 37,000 acres since 1972 — about a quarter of the

land now conserved in Rhode Island.

But volunteer land trusts and conservation commissions can’t

compete with politicians in leadership roles and special interests who have

little problem draining the Ocean State’s natural resources for political and

economic gain.

There are many forces at play — free enterprise, for one — that

don’t favor open-space protection. The biggest, however, has to be the ability

of developers, who already have the ear of politicians, to overwhelm volunteer

organizations and boards with a cache of well-paid attorneys and experts.

John Foley, president of the Tiverton Land Trust, said finding

people who are committed to land preservation and have time to volunteer is

enough of a challenge. Just keeping up with the bookkeeping and day-to-day

operations can be a grind.

The Tiverton Land Trust was

created by residents concerned about plans to build up to 100 single-family

homes on 237 acres of open space. Today, the property is home to the Pardon

Gray Preserve. (Tiverton Land Trust)

“People have busy lives, kids, and most families have two adults

working full-time jobs,” he said. “It can be difficult to carve out the

necessary time.”

The Tiverton Land Trust was

created in 1997 by four residents concerned that one of the few remaining large

farms in town was about to be sold to a developer who planned to build 80 to

100 single-family homes on the 237-acre site. It took three years, plenty of

sweat equity and $1.2 million to keep the property from being developed.

The property was renamed the Pardon Gray Preserve. It abuts Weetamoo Woods, another

preserved property in Tiverton. These two properties shape the start of a

coastal greenway distinguished by the unusual growth of an oak-holly forest.

It’s one of few such forests remaining on the East Coast.

The Tiverton Land Trust has protected nearly 10 properties and

some 475 acres since Matta Farm was saved. Identifying properties to protect,

rallying community support, keeping tabs on conservation easements after

preserved lands change hands and raising money takes time and effort. It’s not an

easy task, especially when the forces of capitalism start pushing.

“We have more properties to preserve than we have dollars to

spend,” Foley told ecoRI News during a visit last month to his downtown

Providence law office. “We’re always trying to find money to protect land.”

Rhode Island’s blight of

vacant big-box stores and their fields of concrete and asphalt, such as this

location in Woonsocket, inundate local waters with polluted stormwater runoff.

These empty spaces are ignored when it comes time to build something new,

usually in the woods. (Joanna Detz/ecoRI News)

Unnatural growth

Biologists, ecologists and foresters ecoRI News has spoken with

over the years have expressed concerns about the condition of Rhode Island’s

dwindling forestlands and the impact their declining health is having on

wildlife, rivers and streams, and the state’s overall well-being.

Recent development projects, such as the corporate office park

being built in the Johnston woods, are further chopping Rhode Island’s

remaining forests into fragmented blocks. A proposed casino in Tiverton, a travel

plaza and truck stop in Hopkinton, and a fossil-fuel power plant in

Burrillville threaten to increase this fragmentation and further impede

nature’s ability to recover, much less thrive.

The continued fragmentation of Rhode Island’s open space increases

the potential for invasive species, such as Japanese barberry and multiflora

rose, to displace established vegetation, decreases the value of habitat and

lessens climate resiliency.

With so many elected officials, such as Gov. Gina Raimondo and

Johnston Mayor Joseph Polisena, who seem to believe the best way for Rhode

Island to move forward is to put cranes in the sky,

it seems prudent that a strong environmental counterbalance is needed to help

steer more development projects to the state’s substantial inventory of vacant

office buildings, big-box stores, old mills and brownfields.

It took five months from the time the Citizens Bank president and

governor held a joint press conference in

March to announce plans to build the banking office park — on 123 acres in

northern Johnston — to cut down the first tree. The office park will feature

2,408 parking spots, a main building, a cafe/amenity building with two stores,

and two office buildings with room for future expansion. No environmental

impact study was done.

Opposition to clear-cutting some 60 acres of woodland never

materialized, and the concerns of a handful of Greenville Avenue residents who

said they felt blindsided by the project’s swift progress were brushed aside by

the mayor.

Swift-moving development projects, like the one in Johnston, bring

up a reasonable question: Should Rhode Island’s collection of 48 land trusts

advocate for open-space protection statewide or should they just focus on

preserving local properties?

The Tiverton Land Trust, for one, doesn’t believe it's in its best

interest to take sides. It’s a view shared by many who volunteer on land

trusts. One of the main reasons land trusts are reluctant to get involved in

matters of advocacy is so not to offend active or potential donors. There’s

also the matter of political pushback.

“We feel that it’s not our place to take positions on political

issues of land development that we aren’t directly involved in,” said Foley, a

Bristol native who has called Tiverton home for the past 27 years.

Those legitimate concerns effectively leave Rhode Island without a

forest-protection equivalent of Save The Bay, as

individual land conservation organizations with a collective lack of resources

can put up little more than some spotty defense.

The Barrington Land Trust, for instance, hasn’t made an

acquisition in a decade. The Johnston Land Trust didn’t make a peep regarding

the Citizens Bank project. The Hopkinton Land Trust didn’t respond to an ecoRI

News request for comment on this story.

“Land trusts have shifted from buying property to managing

conservation easements and community assets,” Friday of the Rhode Island Land

Trust Council said. “Planning and zoning alone won’t keep nice pieces of

property from being developed. Land conservation still plays an important

role.”

Fourteen years ago, in an attempt to facilitate better

cross-communication between Rhode Island’s 48 land trusts, 33 conservation

commissions and 12 watershed groups, Friday and Meg Kerr, now the senior

director of policy for the Audubon Society of Rhode Island, began hosting the Land and Water Conservation Summit.

The daylong conference — like the Compost Conference & Trade Show —

attracts some 300 attendees annually, but it takes time for hands-on workshops

and networking events to collectively sink in.

Land Trust Council board member Trocki regularly attends the Land

and Water Summit and has led a workshop at the annual conference. The Little

Compton resident said the state’s land trusts need support and guidance. She

also said that community-specific movements like “Save the Farm” or “Stop the

Walmart” are effective tools in preserving open space.

“Land conservation is so community driven,” Trocki said. “Land is

personal. It’s about protecting the places that are five minutes from your

house. The stuff you see walking the dog.”

The behind-the-scenes challenge, she said, is managing the

conserved land.

“Communities are passionate about saving land, but the paperwork

is much less sexy,” said Trocki, a self-employed conservation biologist who

often works with private landowners. “We’ve protected all this land but now we

need to manage it and understand it.”

Vision quest

Rhode Island’s cornucopia of state and local plans, strategies,

guidelines and studies related to land use and environmental protections

actually leaves the state without a go-to document. This paperwork mess,

combined with builder-written bills passed annually by the General Assembly

that chip away at buffer zones and other environmental protections, has titled

the paradigm toward development that shuns considering places with existing

infrastructure and paved surfaces.

Trocki said the state lacks a land-protection plan that is

actually working toward something.

“What’s the vision? Where do we want to go?” she asked. “What do

we want our communities to look like fifty to one hundred years from now? What

will our agriculture look like? We don’t spend enough time figuring out where

we want to go.”

There’s no unified plan, Trocki said, because “until you have

experience with a piece of land you have no connection to it.”

Thus, Rhode Island’s 48 land trusts, 39 municipalities, numerous

villages and countless neighborhoods hunker down while the state slowly gets

picked apart.

The creation of pocket parks, grassroots conservation efforts, and

the exhaustive efforts, and money, needed to protect places deemed “special”

can’t keep up with development pressures.

The woods being felled to make way for office parks, casinos and

rest areas are often dismissed as insignificant by those eager to fire up the

bulldozers. The fact is these shrugged-off places provide important ecological

and economical benefits, and doing a better job of keeping them intact would

also help the Ocean State better deal with a changing climate.

The Statehouse, though, decided decades ago that business

relationships are more important than environmental protections. DEM funding

was slashed and its staff cut. It’s now an annual exercise to keep the agency’s

budget level funded.

Friday said DEM employees who worked with land trusts, municipal

officials and private landowners were laid off years ago as assistance

resources evaporated, creating an expertise void that remains today.

Ganz, president of the Salt Ponds Coalition, retired from DEM’s

Department of Natural Resources in 2005, after 35 years. He said the state

agency is too fond of “cockamamie compromises” that help development. He noted

development projects approved in coastal zones in South Kingstown and

Narragansett, such as Green Hill, as prime

examples.

“Two thirty-five Promenade Street is just cubicle upon cubicle,”

Ganz said of DEM’s headquarters in downtown Providence. “When DEM began laying

off staff in the 1980s it was the worker bees, not the top spots, whose jobs

were eliminated. Skeleton crews are managing our state parks and beaches. The

amount of field workers is grossly understaffed.”

Ultimately, a deep-rooted Statehouse mindset that protecting the

environment somehow hinders the economy was developed. Rhode Island’s penchant

for approving environmentally friendly bonds won't curb the state’s fondness

for unnecessarily kissing business ass.

Late last year, DEM send out a Tweet praising the environmental

work of an East Providence business that has spilled some 4,700 gallons of

ethanol during the past few years, and has been fined by the very same agency

for air-pollution violations, for such things as failing to capture volatile

organic compounds and ammonia emissions.

Earlier this year, the governor and the state’s congressional

delegation loudly applauded Citizens Bank for cleaning up a 4-acre wooded

landfill — an illegal operation Rhode Island allowed to operate for a decade

and then ignored for decades more — by covering it with asphalt, concrete and

steel, and clear-cutting 50 more acres.

Earlier this year, the governor and the state’s congressional

delegation loudly applauded Citizens Bank for cleaning up a 4-acre wooded

landfill — an illegal operation Rhode Island allowed to operate for a decade

and then ignored for decades more — by covering it with asphalt, concrete and

steel, and clear-cutting 50 more acres.

In fact, Gov. Raimondo’s “laser focus on economic development,” as

Rep. Jim Langevin, D-R.I., boasted during the Citizens Bank groundbreaking

ceremony in August, forces her administration to see the environment simply as

a means to create jobs and grow the economy.

The Rhode Island Outdoor Recreation

Council was created by the governor to increase “awareness

about the use and enjoyment of recreational and environmental assets.”

But Rhode Island’s wonderful collection of natural resources are

more than economic assets. Our beaches, bays, ponds, lakes, wetlands,

watersheds, salt marshes and forests don’t simply exist to drive tourism. (DEM

notes that this is a $2.4 billion industry that supports 24,000 jobs.) They do

more than provide habitat for the fish we catch and the game we hunt. They also

clean the air, protect our drinking water, nurture the food we grow, and

protect us from storm surge and flooding.

These shared natural resources demand vigilant protection, but the Interim Report of the Rhode Island

Outdoor Recreation Council released in July, for instance,

seems to believe the Ocean State’s economic assets no longer need protection.

According to the report, “Rhode Island has effectively preserved

its considerable natural resources and developed facilities and programming to

enable public enjoyment.”

It also found that the “use of outdoor resources in Rhode Island

by residents and visitors is less than optimal, and there is room to grow this

sector of the state’s economy.”

Properly protecting the environment involves more than building

hiking trails, cleaning seaweed from popular beaches, creating more habitat for

hunting, and developing office parks that offer the community a paved space to

enjoy less trees.

“We’re preserving nature for people — hiking trails, boat ramps.

We’re not preserving biodiversity,” retired DEM employee Rick Enser, who worked

for the state agency for 28 years, told ecoRI News this

past summer. “Building trails and fancy boardwalks look great, but they’re not

helping the environment.”