Experts

paint a dire portrait but leave

a little room for hope.

By Peter Dykstra for The Daily Climate

In a gathering impacted by presidential politics, an all-star cast of

public health experts largely stuck to their own bleak script: Climate change

is poised to unleash an unprecedented, global public health crisis.

In a gathering impacted by presidential politics, an all-star cast of

public health experts largely stuck to their own bleak script: Climate change

is poised to unleash an unprecedented, global public health crisis.

Not even former Vice President Al Gore,

who served as the day's emcee, waded into the political swamp. He presented a

half-hour, health-themed version of his much-lauded slide show.

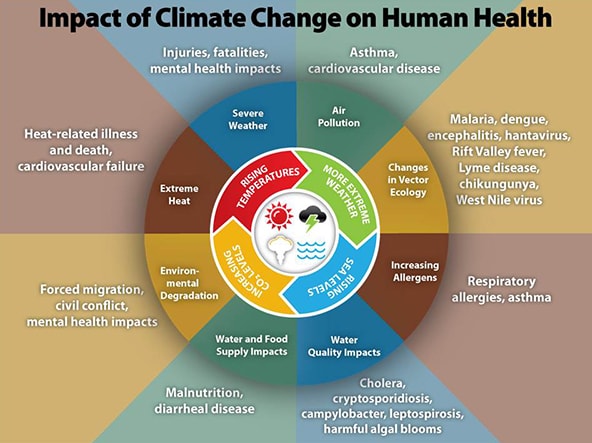

While Gore summarized the gob smacking

array of climate impacts—heat stress, water supplies, food security, mental

health, respiratory and infectious diseases, allergens, and weather

disasters—he left room at the end for some more convenient truths: The world,

he said, is more than able to shift to a clean energy economy, reduce CO2

emissions, and blunt the worst impacts of climate change.

Harvard internist Ashish Jha discussed the climate-related spread of pathogens, and provided one of the conference’s few direct political jabs: “Walls,” he said, “will not keep these pathogens out.”

Activist and philanthropist Laura Turner

Seydel gave an impassioned pitch to participate in the April 22 Scientists’

March in Washington, and to resist the anticipated science and environmental

rollbacks of the Trump Administration.

(Editor's note: The Turner Foundation supports both this

website and this conference.)

But much of the day focused on

overwhelmingly bad news for the world. Harvard’s Sam Myers presented potential

impacts on the global food supply that go beyond the links between extreme

weather and crop failure. Research shows that increased CO2 actually decreases

nutrients in certain food crops, he said.

Rising temperatures, he added, encourage

some forms of plant blight, and could also make the backbreaking outdoor work

of food production impossible in regions like northern Africa.

Psychologist Lise Van Susteren

introduced examples which she said illustrate climate change’s impacts not on

the body, but on the mind. “Climate anxiety” and its sharper cousin, “climate

trauma,” contribute to depression, substance abuse, violence, and more, she

said.

“Destructive impacts from climate

change,” she said, “will someday be treated as if they were child abuse.”

Sir Andy Haines of the London School of

Hygiene and Tropical Medicine tried gamely to provide an antidote to the

barrage of negative news. ”Motivating people through fear, is often difficult,

and can lead to cynicism,” he said. Instead, promoting the health benefits of a

low-carbon economy can be a winning strategy.

The

cost savings from those benefits will more than offset any financial hit

occasioned by moving away from fossil fuels. Haines added the semi-obvious:

Eschewing the car for a bike or a hike cuts emissions and increases health

simultaneously.

Electric cars and bicycles, he said, cut

both emissions and noise, while improved building efficiency can both reduce

heating and cooling and indoor air pollution. Conversion from a heavily

meat-reliant diet would provide twin benefits to health and climate.

Other panelists and speakers discussed

the health impacts of adapting to a changing climate; the unique challenges of

climate-related health issues in poor and minority communities; and the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention’s assistance to state and local governments

on climate issues.

Healthcare advocate Gary Cohen tossed

out a stat that was clearly intended to drive home the public health

community’s role in climate issues: “Our addiction to fossil fuels…. is killing

more people than AIDS, malaria and TB combined.”

Cohen added “In the 21st Century we can

no longer support healthy people on a sick planet.”

The conference closed with a panel on

climate communication. It was mostly a primer for solid climate communication

by health professionals, but one of the panelists was hardly a “usual suspect”

in all things climate.

Jerry Taylor is former vice president of the CATO

Institute, often booked onto TV talk shows to call climate science into

question. For the past few years, he’s burned former political bridges by

acknowledging climate change and advocating a carbon tax. “After 20 years of

wrestling with the climate bear, I lost,” he said.

Taylor’s prescription for persuading

conservatives and Republicans on climate change focused on talking about risk

management, and avoiding discussions of the social cost of carbon or the

massive restructure of the world’s economy.

To

CDC, or not to CDC

The meeting was originally announced in

mid-2016 by the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. After

Donald Trump’s election, the CDC abruptly pulled the plug on the three-day

event, citing “uncertainty” in the agency’s direction under Trump.

Several non-government groups,

universities and philanthropies teamed up to salvage a one-day conference on

short notice. The Carter Center’s Chapel held a capacity crowd of 340,

including 40 accredited journalists.

The short notice perhaps explains the

adorably generic name for the meeting: “Climate & Health Meeting.” In a

surprise appearance, host and former President Jimmy Carter gave the CDC a pass

for cancelling its event.

“The CDC has to be a little more

careful politically,” he said. “The Carter Center doesn’t.”

Politics loomed large in one other

portion of the gathering: A physician scheduled to present in Atlanta ended up

doing so remotely. According to American Public Health Association President Georges

Benjamin, Dr. Nick Watts had recently visited hospitals in Iran, and was denied

a visa to enter the U.S.

The

Daily Climate is an independent, foundation-funded news service covering

energy, the environment and climate change. Find us on Twitter @TheDailyClimate or email editor Brian Bienkowski at

bbienkowski [at] EHN.org