Deep-sea canyons, which

can plunge to depths greater than 7,000 feet, and seamounts, which rise

thousands of feet above the sea floor, create habitats that are home to corals,

fish, marine mammals and turtles. (CLF/NRDC)

By ecoRI News staff

If Interior Secretary

Ryan Zinke’s recommendations to eliminate parts of existing national monuments

are accepted by President Trump, some of the country’s pristine lands and

waters will lose protection from timbering, mining, drilling and overfishing —

a move that could lead to the destruction of treasured lands and marine

ecosystems.

Such a move also would

defy public opinion. Ninety-eight percent of the record-breaking 2.8 million

public comments to the Interior Department asked the federal government to

maintain or expand areas under protection.

The Northeast Canyons

and Seamounts Marine National Monument, off the coasts of Massachusetts and

Rhode Island, remains on the list of monuments under review by the Trump

administration.

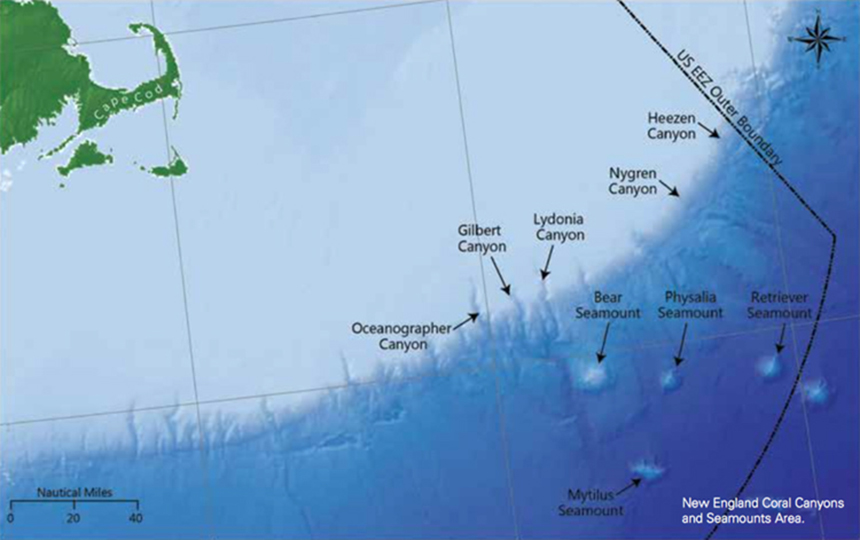

The monument’s steep canyons and ancient volcanoes are home to a rich array of undersea life, including 73 species of coral. The area also provides critical habitat for many species of dolphins and endangered whales.

The monument’s steep canyons and ancient volcanoes are home to a rich array of undersea life, including 73 species of coral. The area also provides critical habitat for many species of dolphins and endangered whales.

Without the protection

of the Antiquities Act, this undisturbed underwater ecosystem would once again

be exposed to threats from commercial fishing and fossil-fuel extraction,

according to Environment America.

Losing protection would deprive future generations of a rich source of scientific knowledge and a natural wonder, said Kelsey Lamp, Oceans Fellow with Environment America.

“The Canyons and

Seamounts Marine National Monument protects critical species, including the

endangered sperm whale,” she said. “The unwise and unpopular choice to stop

protecting America’s lands and waters will ravage pristine places, put wildlife

in danger, and jeopardize scientific and archaeological history.”

The latter reason

explains why most national monuments have been created under the Antiquities

Act, signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906.

“The Antiquities Act is

the first law to establish that archaeological sites on public lands are

important public resources. It obligates federal agencies that manage the

public lands to preserve for present and future generations the historic, scientific,

commemorative, and cultural values of the archaeological and historic sites and

structures on these lands,” according to the National Park Service.

From Roosevelt to Obama,

16 American presidents, Democrats and Republicans, have used the Antiquities

Act to protect more than 150 special places as national monuments. National

monuments aren’t statues — they are federally owned lands and waters that have

historic and/or scientific significance.

In an op-ed published by

ecoRI News in June, Berl

Hartman, a founding director of the New England Chapter of Environmental

Entrepreneurs, wrote, “This

ecologically rich ocean area, about 150 miles off Cape Cod, has five undersea

canyons and four dramatic submarine mountains. It is habitat to more than 1,000

species, including endangered sperm whales and Atlantic puffins. It’s also

replete with corals, some of which are more than a thousand years old and reach

the height of small trees. Scientists who have investigated the area say these

coral formations and marine species are unique and extraordinary to behold.

They are straight out of Dr. Seuss.”

In April, President

Trump ordered Zinke to review 27 of these national treasures. Legal scholars

agree that the president doesn’t have authority under the Antiquities Act to

significantly alter a national monument.

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 affirmed that only Congress can modify national monuments.

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 affirmed that only Congress can modify national monuments.

“Secretary Zinke’s

recommendation foolishly elevates the fleeting value derived from extracting

more resources from these special ecosystems, over the timeless value gained by

preserving America's most precious places for our children, our grandchildren

and generations to come,” Lamp said.