It

wasn't always just another day off.

By Dr. D. Scott Molloy

|

| 1934: Striking mill workers fired upon in Central Falls. |

The state's horny-fisted sons and daughters of toil had marched,

petitioned, and agitated for over a decade.

Rhode Island workers witnessed New York and Oregon pass holiday legislation in 1887, and by the spring of 1893 most other states had followed suit.

The General Assembly, under the prodding of elected representatives from various mill towns, finally joined the bandwagon, and Governor D. Russell Brown signed the authorization.

Rhode Island workers witnessed New York and Oregon pass holiday legislation in 1887, and by the spring of 1893 most other states had followed suit.

The General Assembly, under the prodding of elected representatives from various mill towns, finally joined the bandwagon, and Governor D. Russell Brown signed the authorization.

| Monument erected by RI Labor History Society to honor four workers killed during the Saylesville Massacre of 1934. |

Monday, September 4, 1893 was a beautiful day by all accounts.

Tens of thousands of Rhode Islanders walked or took a horse car or electric

trolley to the capital city.

Three thousand union members lined up in divisions behind the Caledonia Fife and Drum Band, the twelve-piece Olneyville Cadet Corps, L'Harmonie Canadienne Band, and several other musical groups.

Both the cigar makers and the horseshoers fielded floats. The cigar makers contrasted the favorable conditions in a union shop against the unregulated toil in a tenement sweatshop in a vivid display.

Three thousand union members lined up in divisions behind the Caledonia Fife and Drum Band, the twelve-piece Olneyville Cadet Corps, L'Harmonie Canadienne Band, and several other musical groups.

Both the cigar makers and the horseshoers fielded floats. The cigar makers contrasted the favorable conditions in a union shop against the unregulated toil in a tenement sweatshop in a vivid display.

The Rhode Island Central Labor Union, predecessor to the

state AFL-CIO today, sponsored the parade.

Eighteen skilled unions participated, including the Carpenters Local 94,

Painters and Decorators Number 195, and Providence Typographical Union Local

33.

Those three unions still exist a century later. Other organizations like the Cornice Workers, Mule Spinners, and Pavers and Pounders Unions have long since affiliated with other labor groups as technology altered jobs over the years.

Many participating unions that day carried sparkling new banners; the printers wore fancy badges that cost eight cents each; and the Plasterers sported white hats, aprons, and canes.

Those three unions still exist a century later. Other organizations like the Cornice Workers, Mule Spinners, and Pavers and Pounders Unions have long since affiliated with other labor groups as technology altered jobs over the years.

Many participating unions that day carried sparkling new banners; the printers wore fancy badges that cost eight cents each; and the Plasterers sported white hats, aprons, and canes.

The march began at 9:30 and "put all previous civic

processions in the shade." Starting from Market Square, the procession

tramped to a reviewing stand in Exchange Place and then snaked its way through

downtown, countermarching on several packed thoroughfares.

Enthusiastic working people cheered their class colleagues the entire route. The local union newspaper, Justice, remarked with male conceit that "the principal streets were packed by the crowds of wives, sisters, and sweethearts of the toilers." An estimated 10,000 spectators jammed the city wharves off Dyer Street at the parade's end to embark on a steamboat trip to Rocky Point.

Enthusiastic working people cheered their class colleagues the entire route. The local union newspaper, Justice, remarked with male conceit that "the principal streets were packed by the crowds of wives, sisters, and sweethearts of the toilers." An estimated 10,000 spectators jammed the city wharves off Dyer Street at the parade's end to embark on a steamboat trip to Rocky Point.

Rocky

Point

The throng of revelers was so immense that the Continental

Steamboat Company had to engage several of its competitors to handle the crowd,

the largest of the season at the amusement park. Upon arrival, the marchers

reassembled and trooped to a grove near the park pavilion for a two-hour rally.

The throng of revelers was so immense that the Continental

Steamboat Company had to engage several of its competitors to handle the crowd,

the largest of the season at the amusement park. Upon arrival, the marchers

reassembled and trooped to a grove near the park pavilion for a two-hour rally. Speeches by labor notables from around New England invigorated the listeners by lambasting the ruling industrial elite. After the formalities, guests filled every available seat in the dining hall for the obligatory Rhode Island clam dinner. Visitors then patronized the amusement rides or nearby ball field "and saw the victors in the various games wipe the ground with their opponents."

The editors of the Providence Journal marveled,

although not directly, about the exemplary behavior of the working class crowd.

No arrests or trouble marred labor's first official holiday in Rhode Island.

Both Capital and Labor, however, felt a deep uneasiness about conditions in the state and the nation. Although there had been a few good economic years of late, the lingering memory of the drawn-out panic of 1877, and a string of subsequent recessions strained the uneasy truce between the two.

Both Capital and Labor, however, felt a deep uneasiness about conditions in the state and the nation. Although there had been a few good economic years of late, the lingering memory of the drawn-out panic of 1877, and a string of subsequent recessions strained the uneasy truce between the two.

Local

Labor History

Employer-employee friction was certainly not unique to Rhode

Island, but several local conditions stoked the fires of class antagonism. A

half century earlier workers mobilized and even armed themselves in the

legendary Dorr War of 1842.

They attempted to end political discrimination against the working class by altering the state constitution to allow poor citizens to vote. Rhode Island authorities called out the militia, split native-born workers from their Irish-born allies and quelled the uprising.

Nevertheless, workers continued to maintain their non-partisan traditions by banding together in the years before and after the Civil War. Throughout the 1870s, factory hands staged walkouts in an effort to have workdays shortened to ten hours. In 1885 District 99, the Rhode Island branch of the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, went public and shook the state's power structure.

They attempted to end political discrimination against the working class by altering the state constitution to allow poor citizens to vote. Rhode Island authorities called out the militia, split native-born workers from their Irish-born allies and quelled the uprising.

Nevertheless, workers continued to maintain their non-partisan traditions by banding together in the years before and after the Civil War. Throughout the 1870s, factory hands staged walkouts in an effort to have workdays shortened to ten hours. In 1885 District 99, the Rhode Island branch of the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, went public and shook the state's power structure.

The

Knights

The state's Yankee manufacturers had aligned themselves into an

informal ruling political party. With the demobilization of the militia after

the Dorr War in 1842, the mill barons employed the columns of the Providence

Journal to demonstrate that the power of the pen was greater than the

sword, at least in quieter times.

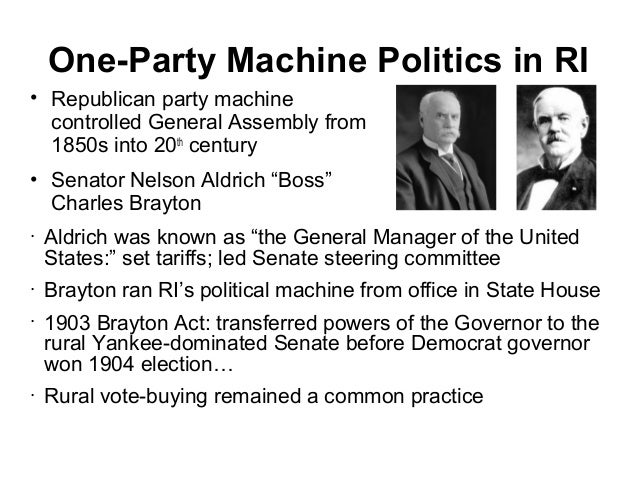

The nascent Republican Party became the standard bearer of genteel and corrupt rule in Rhode Island after the Civil War.

Influential politicos like Henry Bowen Anthony, Charles "Boss" Brayton, and United States Senator Nelson Aldrich maintained the constitutional machinery of minority rule while imaginatively scheming to perpetuate that control over future generations.

On a day-to-day level mill owners and foremen controlled the workday, company housing, and factory stores.

The nascent Republican Party became the standard bearer of genteel and corrupt rule in Rhode Island after the Civil War.

Influential politicos like Henry Bowen Anthony, Charles "Boss" Brayton, and United States Senator Nelson Aldrich maintained the constitutional machinery of minority rule while imaginatively scheming to perpetuate that control over future generations.

On a day-to-day level mill owners and foremen controlled the workday, company housing, and factory stores.

No simple trade unionism could undermine such a malignant system.

The Knights, however, aimed beyond mere labor reform. They envisioned a new

commonwealth where all share in America's bounty.

The Knights enrolled women, African-Americans, and immigrants alongside the predominantly white male workforce. They organized cooperative stores for inexpensive products, ran a string of union-endorsed restaurants for workers, and even operated a children's nursery in Olneyville. In the shops they established grievance procedures, democratic practices, and even controlled production in a few places.

Politically, the Knights agitated for the passage of the Bourn Amendment, a state Bureau of Labor Statistics, and safety legislation. Although the grand vision eventually failed in the late 1800s due to a variety of factors, a local writer for the Knights exclaimed that "One need not go to the state house to perceive that labor breathes freer in Rhode Island than ever before."

The Knights enrolled women, African-Americans, and immigrants alongside the predominantly white male workforce. They organized cooperative stores for inexpensive products, ran a string of union-endorsed restaurants for workers, and even operated a children's nursery in Olneyville. In the shops they established grievance procedures, democratic practices, and even controlled production in a few places.

Politically, the Knights agitated for the passage of the Bourn Amendment, a state Bureau of Labor Statistics, and safety legislation. Although the grand vision eventually failed in the late 1800s due to a variety of factors, a local writer for the Knights exclaimed that "One need not go to the state house to perceive that labor breathes freer in Rhode Island than ever before."

The Knights bequeathed their legacy of industrial democracy to the

Rhode Island Central Labor Union, an amalgamation of skilled trades, which the

Holy Order helped form in 1884. The symbolic concept of the labor parade,

festival, and holiday was well known to both groups.

In fact Rhode Island labor unions hosted a mammoth parade and excursion to Rocky Point on August 23, 1882—just two weeks before the "first" Labor Day parade stepped off in New York City. Throughout the 1880s local unions marched, sponsored picnics, and petitioned the Legislature for a legal holiday.

In fact Rhode Island labor unions hosted a mammoth parade and excursion to Rocky Point on August 23, 1882—just two weeks before the "first" Labor Day parade stepped off in New York City. Throughout the 1880s local unions marched, sponsored picnics, and petitioned the Legislature for a legal holiday.

Strategic

Retreat

When the General Assembly and the Republican machine capitulated

to labor's demand for its own holiday in 1893, it was less a surrender than a

strategic retreat. There were neither penalties for staying open nor any

compensation for lost time.

With the specter of the Knights of Labor still haunting the industrial establishment, the powers-that-be probably figured that a tactful concession on the issue of a legal Labor Day might serve as an escape valve for disenchanted workers and their leaders during hard economic times.

With the specter of the Knights of Labor still haunting the industrial establishment, the powers-that-be probably figured that a tactful concession on the issue of a legal Labor Day might serve as an escape valve for disenchanted workers and their leaders during hard economic times.

Some factory owners diplomatically welcomed the opportunity to

provide a payless holiday. Already local firms were cutting wages and

shortening hours.

At Gorham's, 200 out of 1500 were laid off while those on the job toiled only four days a week; at Brown and Sharpe more than half of the 1100 workers were out.

The Journal editors fretted about labor-led unemployment demonstrations in New York City and predicted, "it is probable that the tide of business depression may yet rise high enough to cause trouble in New England."

At Gorham's, 200 out of 1500 were laid off while those on the job toiled only four days a week; at Brown and Sharpe more than half of the 1100 workers were out.

The Journal editors fretted about labor-led unemployment demonstrations in New York City and predicted, "it is probable that the tide of business depression may yet rise high enough to cause trouble in New England."

Labor, for its part, had circled the wagons. The Rhode Island

Central Labor Union affiliated with Samuel

Gompers' American Federation of Labor in February 1893, as a

way to strengthen national solidarity.

The building trades had formed a protective council in the state in April in order to foster greater cooperation among construction unions. However, despite the militant rhetoric that still sallied forth from a united movement, a great change had occurred since the recent demise of the Knights and the ascendancy of the Central Labor Union.

The building trades had formed a protective council in the state in April in order to foster greater cooperation among construction unions. However, despite the militant rhetoric that still sallied forth from a united movement, a great change had occurred since the recent demise of the Knights and the ascendancy of the Central Labor Union.

12,000

Members

At its peak the Knights claimed 12,000 members scattered among a

far-flung Rhode Island workforce that would be characterized today as

"multi-cultural."

On the other hand, the new AF of L affiliate could claim only 5,000 workers, heavily concentrated among the skilled. Their predominantly white, male members represented what historians would later call the "old immigrants"—English, Irish, and German craftsmen.

Most jobs in the state were unskilled ones, symbolized by faceless mill hands increasingly drawn from eastern and southern Europe and French-Canada—America's "new immigrants."

The Knights' inclusive solid phalanx gave way to the well-organized but narrowly drawn population of the American Federation of Labor. This union wanted a piece of the pie certainly, but not the whole pastry.

On the other hand, the new AF of L affiliate could claim only 5,000 workers, heavily concentrated among the skilled. Their predominantly white, male members represented what historians would later call the "old immigrants"—English, Irish, and German craftsmen.

Most jobs in the state were unskilled ones, symbolized by faceless mill hands increasingly drawn from eastern and southern Europe and French-Canada—America's "new immigrants."

The Knights' inclusive solid phalanx gave way to the well-organized but narrowly drawn population of the American Federation of Labor. This union wanted a piece of the pie certainly, but not the whole pastry.

Live

On Other's Labor

As Rhode Island workers marched into history that beautiful Monday

morning, September 4, 1893, sweating editors at the Providence Journal dripped

acid on their written opinion of the festivities.

As Rhode Island workers marched into history that beautiful Monday

morning, September 4, 1893, sweating editors at the Providence Journal dripped

acid on their written opinion of the festivities. "If workingmen would employ Labor Day in reflecting on how much has been accomplished for labor in the last five centuries and how little of it has been accomplished by the quarrels and struggles of labor and capital, the holiday would be a good deal more beneficial than it is to be feared its present method of observance makes it."

Not to be outdone, a set of equally opinionated editors wrote in the first issue of the Central Labor Union's own weekly newspaper, Justice: "Labor Day is frowned upon only by those who wish to live upon [others'] labor. And they know that when Labor once recognizes its rights, it will assert its independence and free itself from the shackles of wage slavery which now keep the toiler bound fast to the millstone of monopoly and which is grinding and crushing the victims to fill the coffers of its masters."

With those editorial outbursts Labor Day began its initial observance in Rhode Island.

Centennial

Celebration

1993 marked the centennial celebration. Over the years, organized

labor transformed the traditional working class into a reputable middle class.

During the Great Depression the Congress of Industrial Organization signed up

the unskilled Americans left behind by the older federation.

In 1955 both the AF of L and the CIO ended their cleavage through a merger. As union members gained respectability and lost their grandparents' fervor, parades and picnics came into disfavor.

As early as 1937 the Rhode Island Labor News complained that "with the coming of the automobile, which afforded opportunities to workers to take their families out for a weekend trip, it became more and more difficult to secure large numbers as participants in parades." The holiday became the exit ramp from summer; one last three day weekend to mark the passing of seasons.

In 1955 both the AF of L and the CIO ended their cleavage through a merger. As union members gained respectability and lost their grandparents' fervor, parades and picnics came into disfavor.

As early as 1937 the Rhode Island Labor News complained that "with the coming of the automobile, which afforded opportunities to workers to take their families out for a weekend trip, it became more and more difficult to secure large numbers as participants in parades." The holiday became the exit ramp from summer; one last three day weekend to mark the passing of seasons.

In recent years the state AFL-CIO has sponsored a Labor and Ethnic

Heritage Festival on the grounds of the Slater Mill

Historic Site in Pawtucket. Music and dance from Southeast

Asia, Central America, and even Russia punctuate the celebration.

As new groups of immigrant workers arrive on our shores and native-born employees discover they are suddenly disposable in a global economy, organized labor may have to compose a new mission statement. And Labor Day may have an entirely new lease on life after 100 years.

As new groups of immigrant workers arrive on our shores and native-born employees discover they are suddenly disposable in a global economy, organized labor may have to compose a new mission statement. And Labor Day may have an entirely new lease on life after 100 years.

D. Scott Molloy is a professor of History at the University of

Rhode Island. A former bus driver for RIPTA, he is the author of Trolley Wars: Streetcar Workers on the Line, and

an Images of America book entitled All Aboard: The History of Mass Transportation in

Rhode Island. As a member of the Irish

Famine Memorial Committee he educates the public about the role

of Irish immigrants in Rhode Island labor history. 10,000 pieces from his

extensive collection of labor movement memorabilia are preserved in the Smithsonian.