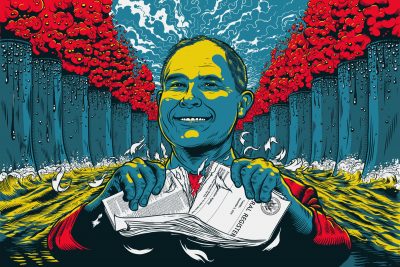

Trump’s

Dark

Deregulation

At an event on

December 14 to tout his administration’s efforts to rid the federal government

of what he contends is burdensome red tape, President Donald Trump used

oversized gold scissors to cut a piece of red ribbon strung between two stacks

of paper.

At an event on

December 14 to tout his administration’s efforts to rid the federal government

of what he contends is burdensome red tape, President Donald Trump used

oversized gold scissors to cut a piece of red ribbon strung between two stacks

of paper.

In short order, he

promised, his administration would excise some 165,000 of the more than 185,000

pages in the Code of Federal Regulations.

That’s no easy task.

Changing federal regulatory laws can mean a congressional slog. And for federal

agencies to rescind rules, they must engage in a time-consuming process that

opens them to public scrutiny and potential legal challenges.

But there are ways to

get around these impediments. Collectively, you might call them dark

deregulation.

The Data Dump

An agency can’t

regulate blind. Deprive a regulator of information, and it can’t do much.

The Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission enforces workplace discrimination laws. In September

2016, it announced that it would require certain larger

employers to report wage and hour data by gender, ethnicity

and race. “Collecting pay data is a significant step forward in addressing

discriminatory pay practices,” Jenny Yang, who was the EEOC’s chair, said at

the time.

This August, the White

House budget office suspended the plan indefinitely while the office reviews

it. The decision relied on an obscure law called the Paperwork Reduction Act.

Passed in 1980, Congress intended it as a way to cut down on interminable

compliance requirements.

But from the beginning, opponents warned it would make it harder for agencies to do their jobs. In a letter to the EEOC, Neomi Rao — the administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs — wrote that the EEOC’s plan to collect salary data “lack[ed] practical utility” and was “unnecessarily burdensome.”

But from the beginning, opponents warned it would make it harder for agencies to do their jobs. In a letter to the EEOC, Neomi Rao — the administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs — wrote that the EEOC’s plan to collect salary data “lack[ed] practical utility” and was “unnecessarily burdensome.”

Although the hold on

collection of salary data is not permanent, equal-pay organizations read Rao’s letter as the death knell for

the data collection effort, which they expect will hinder the government’s

ability to bring discrimination cases against employers.

Organizations representing employers have argued it won’t since the salary data was too generic to allow the EEOC to detect wage discrimination accurately anyway.

Organizations representing employers have argued it won’t since the salary data was too generic to allow the EEOC to detect wage discrimination accurately anyway.

This use of the

Paperwork Reduction Act may not be a one-off. Rao signaled recently that her staff was likely to

continue to wield the law to limit agency initiatives to gather information.

The Enforcement Strike

Sometimes, just doing

less adds up to deregulation, in a form that’s difficult to identify and even

harder to challenge in court.

Two studies of

Securities and Exchange Commission data published last month offer an

illustration.

A report by researchers at New York University and Cornerstone Research, a consulting firm, observed a steep slide in new enforcement actions against publicly traded companies and their subsidiaries during the first six months of SEC Chairman Jay Clayton’s tenure.

An analysis by Urska Velikonja, a law professor at Georgetown University, found a similar decline in new actions brought against public Wall Street financial firms and subsidiaries.

A report by researchers at New York University and Cornerstone Research, a consulting firm, observed a steep slide in new enforcement actions against publicly traded companies and their subsidiaries during the first six months of SEC Chairman Jay Clayton’s tenure.

An analysis by Urska Velikonja, a law professor at Georgetown University, found a similar decline in new actions brought against public Wall Street financial firms and subsidiaries.

That pattern sets

Clayton apart from two SEC chairs appointed by President Barack Obama, Mary

Schapiro and Mary Jo White, Velikonja said.

Data she shared with ProPublica show that the number of new enforcement actions remained roughly steady or rose in the months after Schapiro and White took office, in 2009 and 2013 respectively.

Data she shared with ProPublica show that the number of new enforcement actions remained roughly steady or rose in the months after Schapiro and White took office, in 2009 and 2013 respectively.

The 2017 data

indicates that “something has changed,” Velikonja said. “Why it changed is a

much more complicated narrative.”

At a conference

earlier this fall, Steven Peikin, who co-directs the SEC’s Enforcement

Division, suggested that the agency may start pursuing fewer

cases, devoting resources only to those cases that “send a broader message.”

(Peikin’s co-director, Stephanie Avakian has disputed claims that the SEC is giving Wall

Street a pass.)

“What we’ve seen thus

far is very surprising,” said Sara Gilley, a principal at Cornerstone. “We did

not expect such a large drop-off.” But, she added, “it’s too early to tell if

the change is because Clayton is going after big cases,” which would take time

to build, or for some other reason, like the SEC simply cutting back on

enforcement.

The Budget Squeeze

The White

House’s decision to impose a so-called “regulatory

budget” on government agencies is one of its more innovative moves to shrink

the footprint of the federal bureaucracy. Each agency’s allotment creates a

sort of deregulatory cap-and-trade system designed to force the agency to make

it cheaper for the private sector to comply with rules.

The budget flows

chiefly through the White House budget office — and, in particular, Rao’s

regulatory affairs staff — often called the “gatekeeper” of the administrative

state, which does such wonkish work that it draws little public attention or

pushback.

“We’re small but mighty,” Rao said of her staff at an October event at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington.

“We’re small but mighty,” Rao said of her staff at an October event at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington.

The regulatory budget

caps the costs an agency can impose on industry each year through rule-making.

No matter the social benefit of the new rule, the agency has to offset the cost

of complying with it by reducing what it costs to comply with at least two

existing rules.

“A regulatory budget

could have the most far-reaching impact of any executive branch regulatory

reform” since the Ford administration, researchers at the Brookings

Institution wrote in October.

The administration believes the regulatory budget is working. On Thursday, it reported that agencies across the federal government (excluding some independent agencies, like the SEC) had slashed annual compliance costs by $570 million for the 2017 fiscal year. For 2018, the White House announced, agencies collectively will have to cut annual compliance costs by more than $685 million.

The Slowdown

The rush toward the

end of the Obama administration to finalize lingering rules left many of them

to go into effect after Jan. 20, when Trump took office. That left open a

possibility the White House has embraced: delay.

It’s a lot easier to

justify postponing a rule than it is to justify killing or revising it. While

the agency decides the rule’s ultimate fate, the people and businesses affected

are free to ignore the rule’s requirements.

After a spate of miner

deaths between 2013 and 2015, the Mine Safety and Health Administration

proposed a rule to protect miners at hard rock and other non-coal mines. The

rule was simple. Mine operators would have to inspect work sites for hazards

before a new shift of miners began work. Previously, operators could inspect

the site after work had begun.

MSHA finalized the

rule in January and gave mine operators four months to comply. Since then, the

agency has repeatedly delayed the rule, maintaining that mine operators needed more time to

come into compliance. How much time? Nearly a year and a half. The rule is now

set to go into effect in June 2018.

The rationale for

delay doesn’t make much sense to Joseph Main, who headed MSHA during the Obama

administration. During his tenure, he said, it took only a few months to get

mine operators up to speed on much more complicated regulatory changes.

“It was such a

common-sense rule,” Main said. “It’s really simple. The time taken — the delay

to train up the industry — I think is beyond belief here, to say the least.”

By September, another

reason for the delay had emerged: MSHA has proposed relaxing the rule so mine operators could inspect

work sites “as miners begin work.”

The Expanding Exemptions

Many agency rules

include exceptions to their requirements — when or where the rule applies, to

whom it applies. Interpreting exceptions expansively or using them more

aggressively are ways to cut back on a rule’s practical effect without revising

it or taking it off the books.

Take the environmental

reviews mandated by a 1970 law called the National Environmental Policy Act.

NEPA requires agencies across the federal government to document the

environmental impacts of major actions they plan to take. The process includes

a chance for the public to comment on the government’s plans.

The Trump

administration earlier this year announced plans to reduce “unnecessary burdens and

delays” caused by NEPA reviews. To help achieve its goal, the administration

has asked federal agencies to turn to “categorical exclusions.”

Those are categories of government action that don’t require an environmental review. Examples include approving construction of short natural gas pipelines and laying a bike path.

Those are categories of government action that don’t require an environmental review. Examples include approving construction of short natural gas pipelines and laying a bike path.

Agencies are

listening. Last month, for instance, a task force at the Department of

Energy recommended that the agency consider granting more

categorical exclusions. It singled out as an example geothermal energy projects

on federal lands. (The recommendations remain under White House review.)

The NEPA process often

takes months or years, and it is a longtime target of conservative

groups, which say it needlessly delays energy and

infrastructure projects and increases their cost. But environmental groups

worry that an overeager turn to categorical exclusions will undermine NEPA’s

core purpose.

“There are communities

where, but for NEPA, nobody would know a highway is going to be built,” said

Scott Slesinger, the legislative director for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“The idea is, when the government comes in to do something, they should look

before they leap.”

Ian MacDougall is a senior reporting fellow at ProPublica.