New

understanding of ocean turbulence could improve climate models

Kevin Stacey, Brown University

Brown

University researchers have made a key insight into how high-resolution ocean

models simulate the dissipation of turbulence in the global ocean. Their

research, published in Physical Review Letters, could be helpful in developing

new climate models that better capture ocean dynamics.

Brown

University researchers have made a key insight into how high-resolution ocean

models simulate the dissipation of turbulence in the global ocean. Their

research, published in Physical Review Letters, could be helpful in developing

new climate models that better capture ocean dynamics.

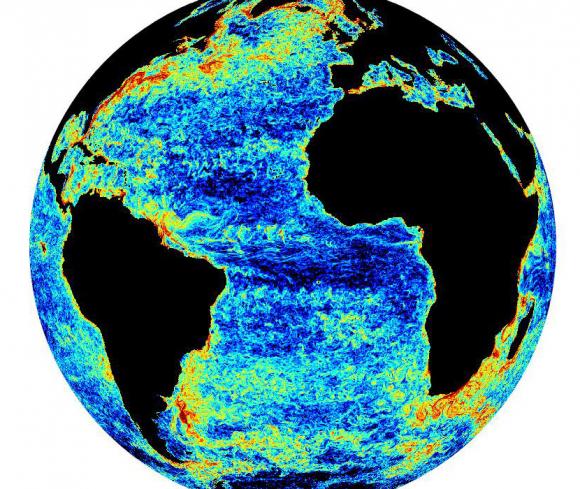

The

study was focused on a form of turbulence known as mesoscale eddies, ocean

swirls on the scale of tens to hundreds of kilometers across that last anywhere

from a month to a year. These kinds of eddies can pinch off from strong

boundary currents like the Gulf Stream, or form where water flows of different

temperatures and densities come into contact.

“You

can think of these as the weather of the ocean,” said Baylor Fox-Kemper,

co-author of the study and an associate professor in Brown’s Department of

Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences.

“Like storms in the atmosphere, these eddies help to distribute energy, warmth, salinity and other things around the ocean. So understanding how they dissipate their energy gives us a more accurate picture of ocean circulation.”

“Like storms in the atmosphere, these eddies help to distribute energy, warmth, salinity and other things around the ocean. So understanding how they dissipate their energy gives us a more accurate picture of ocean circulation.”

The

traditional theory for how small-scale turbulence dissipates energy states that

as an eddy dies out, it transmits its energy to smaller and smaller scales. In

other words, large eddies decay into smaller and smaller eddies until all the

energy is dissipated. It’s a well-established theory that makes useful

predictions that are widely used in fluid dynamics. The problem is that it

doesn’t apply to mesoscale eddies.

“That

theory only applies to eddies in three-dimensional systems,” Fox-Kemper said.

“Mesoscale eddies are on the scale of hundreds of kilometers across, yet the

ocean is only four kilometers deep, which makes them essentially

two-dimensional. And we know that dissipation works differently in two

dimensions than it does in three.”

Rather

than breaking up into smaller and smaller eddies, Fox-Kemper says,

two-dimensional eddies tend to merge into larger and larger ones.

“You

can see it if you drag your finger very gently across a soap bubble,” he said.

“You leave behind this swirly streak that gets bigger and bigger over time.

Mesoscale eddies in the global ocean work the same way.”

This

upscale energy transfer is not as well understood mathematically as the

downscale dissipation. That’s what Fox-Kemper and Brodie Pearson, a research

scientist at Brown, wanted to look at with this study.

They

used a high-resolution ocean model that has been shown to do a good job of

matching direct satellite observations of the global ocean system. The model’s

high resolution means it’s able to simulate eddies on the order of 100 kilometers

across. Pearson and Fox-Kemper wanted to look in detail at how the model dealt

with eddy dissipation in statistical terms.

“We

ran five years of ocean circulation in the model, and we measured the damping

of energy at every grid point to see what the statistics are,” Fox-Kemper said.

They found that dissipation followed what’s known as a lognormal distribution —

one in which one tail of the distribution dominates the average.

“There’s

the old joke that if you have 10 regular people in a room and Bill Gates walks

in, everybody gets a billion dollars richer on average — that’s a lognormal

distribution,” Fox-Kemper said. “What it tells us in terms of turbulence is

that 90 percent of the dissipation takes place in 10 percent of the ocean.”

Fox-Kemper

noted that the downscale dissipation of 3-D eddies follows a lognormal

distribution as well. So despite the inverse dynamics, “there’s an equivalent

transformation that lets you predict lognormality in both 2-D and 3-D systems.”

The

researchers say this new statistical insight will be helpful in developing

coarser-grained ocean simulations that aren’t as computationally expensive as

the one used in this study. Using this model, it took the researchers two

months using 1,000 processors to simulate just five years of ocean circulation.

“If

you want to simulate hundreds or thousands or years, or if you want something

you can incorporate within a climate model that combines ocean and atmospheric

dynamics, you need a coarser-grained model or it’s just computationally

intractable,” Fox-Kemper said.

“If we understand the statistics of how mesoscale eddies dissipate, we might be able to bake those into our coarser-grained models. In other words, we can capture the effects of mesoscale eddies without actually simulating them directly.”

“If we understand the statistics of how mesoscale eddies dissipate, we might be able to bake those into our coarser-grained models. In other words, we can capture the effects of mesoscale eddies without actually simulating them directly.”

The

results could also provide a check on future high-resolution models.

“Knowing

this makes us much more capable of figuring out if our models are doing the

right thing and how to make them better,” Fox-Kemper said. “If a model isn’t

producing this lognormality, then it’s probably doing something wrong.”

The

research was supported by the National Science Foundation (OCE-1350795), Office

of Naval Research (N00014-17-1-2963) and the National Key Research Program of

China (2017YFA0604100).