Regardless of What He Thinks, There’s

Nothing Easy About International Trade or Economics

By

Terry H. Schwadron, DCReport New York Editor

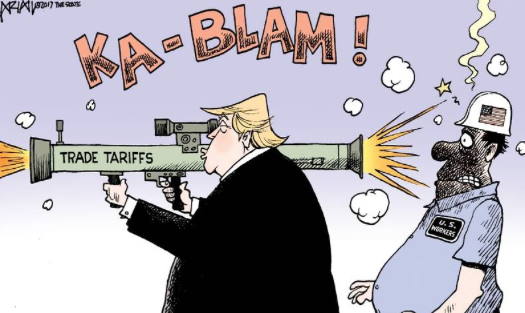

Despite a campaign of

bluster about unfair trade advantage for countries dealing with the United

States, Trump’s decision this week to order unilateral 25% tariffs on imported

steel and 10% on imported aluminum—all in the name of protecting the American

worker in Rust Belt states—came like a thunderbolt. A final decision still

looms for next week.

Despite a campaign of

bluster about unfair trade advantage for countries dealing with the United

States, Trump’s decision this week to order unilateral 25% tariffs on imported

steel and 10% on imported aluminum—all in the name of protecting the American

worker in Rust Belt states—came like a thunderbolt. A final decision still

looms for next week.

The decision came at

the surprise of staffers as well as other countries as well as people who think

about this sort of thing for a living.

The stock market

dropped 2%, other countries talked of retaliation and talk of an international

trade war drew this Trump tweet:

When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win. Example, when we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don’t trade anymore—we win big. It’s easy!”

Let’s just assert that

economic policy-making isn’t easy, ever, and, as usual, the president went with

his gut rather than his White House counsel.

So, as citizens, we’re left to make sense of the policies and to ponder whether they will prove good or bad for the country, because both results are reasonable to foresee.

Because we are not

economists, I think we want to know why now? Was it thought through? What will

be the effects? And what can we expect next?

How former Trump advisor Carl Icahn made out like a bandit

Trump’s former adviser, corporate raider Carl Icahn, dumped millions of dollars worth of stocks tied to the steel industry one week before the president announced new tariffs on steel and aluminum.

Icahn sold $31.3 million

worth of stock in the Manitowoc Company, a manufacturer of construction cranes,

according to a Feb. 22 SEC filing. Icahn, who had not traded the

stock in more than three years, sold his shares for about $32 to $34 each;

Manitowoc’s stock fell to $26 after Trump’s announcement.

Icahn, whose

relationship with Trump goes back to the 1990s, endorsed Trump during the 2016

election. He resigned from his position as a special adviser on regulatory

issues in August amid concerns over his possible conflicts of interest.

Why is Trump doing this?

The best comment I’ve

seen on the Why was from a Washington Post business writer:

“Trump often likes to sow misdirection, running the White House like a never-ending reality show where only he knows the plot. But even by his standards, the day-long period that ended Thursday left some senior aides and Republican lawmakers wondering whether the White House had finally come unmoored, detached from any type of methodology that past presidents have relied on to run the country and lead the largest economy in the world.”

The surprise

announcements came over the objections and advice of the National Economic

Council, whose director, Gary Cohn, probably will become among the next

advisers to leave the White House because he was outmaneuvered by Commerce

Secretary Wilbur Ross and trade adviser Peter Navarro.

By all accounts, the

president had grown tired of talking points and economic theory and decided to

make policy his own way.

There also have been

plenty of mentions of the fact that Trump has had a bad week that included

Jared Kushner’s demotion, continuing Russia investigations and the guns debate,

and wanted to turn the public’s attention to, well, himself and fulfilling a

campaign pledge. The announcement comes as a tight congressional race looms in

Western Pennsylvania, steel country.

Effects

Bloomberg noted:

“For all the Sturm und Drang coming out of the White House, China’s trade in steel and aluminum with the U.S. isn’t all that significant. The larger steel side of it represents about 0.2% of the global trade, and just 3.3% of China’s exports to America, on a par with the trade in shoes.”

By contrast, most

imported steel imports come from strong allies like Canada, South Korea,

Mexico, Germany, Japan and Brazil.

Undoubtedly, U.S.

steel and aluminum manufacturers, which together have lost about 26,000 jobs in

recent decades, will prosper.

Over-simplifying, if

imported steel costs more than domestic steel, domestic jobs should increase.

Others, including the

stock market crowd, seem to see the corollary: Imports won’t stop. Instead, the

increased costs will be passed along to U.S. consumers in products made of

steel and aluminum, from cars to beer cans.

That, in turn, will

force manufacturing pressures and actually cause losses of U.S. jobs.

Manufacturers “will be

paying higher prices for our stainless steel going forward, ironically making

us less competitive against foreign-finished goods,” said Greg Owens, the

president of the flatware maker Sherrill Manufacturing, in a press release.

He wants the White

House to take measures to ensure that foreign goods would not be cheaper as a

result of the tariffs, “a critical next step that if left unaddressed will turn

this first positive step into a catastrophe for American manufacturing.”

From a worker’s point

of view, tariff protections may seem very desirable in the short term—after

all, it is their jobs we are discussing—but new boutique steel manufacturing

that arises to meet specific market needs almost certainly will be highly

automated ventures, with fewer of the lost steel and aluminum jobs restored.

Just my take, but how much better it would be economically for the president to

back large-scale job skill training programs.

You can believe in a

slogan or you can measure how this, like so many other Trump policies, actually

works out.

Next: Trade war?

The Atlantic Magazine

challenges the notion that tariffs will protect American jobs or bolster

national security, saying, “They’ll likely do neither.”

In pursuit of “free,

fair and SMART TRADE,” as the president tweeted, targeting China—apparently

incorrectly—for unfair trade practices that hurt American blue-collar workers

might backfire, raising costs for American consumers, hurting American

exporters, straining American economic relationships around the world and

ultimately slowing growth. Trump has also said that U.S. defense manufacturers,

who rely on steel, need protection as a national security issue.

China has made light

of the specifics but warns that retaliation is always possible. So are other

countries. Of course, talk is easy, but there will be hearings before the World

Trade Organization over the unilateral Trump announcements.

“If the United States

goes down this path for steel and aluminum, there is little to prevent other

countries from arguing that they too are justified to use similar exceptions to

halt U.S. exports of completely different products,” the Atlantic quoted Chad

P. Bown of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a

Washington-based think tank broadly supportive of free trade.

“Because this leads to a downward spiral and erodes meaningful obligations under international trade rules, justifying import restrictions based on national security is really the ‘nuclear option’.”

“Because this leads to a downward spiral and erodes meaningful obligations under international trade rules, justifying import restrictions based on national security is really the ‘nuclear option’.”

Trump may think that

trade wars are “easy to win,” but other countries, economists and financial

markets don’t.

This tariff

announcement is diametrically opposed to the goals of NAFTA, the North American

Free Trade Agreement, which is currently in discussion.

Agricultural states

were bracing to hear bad counter-tariff announcements from countries to which

American produce exports.

The Atlantic said a

study of similar trade actions taken by the George W. Bush administration found

that they cost an estimated 200,000 jobs, including roughly 11,000 in Ohio,

10,000 in Michigan, 10,000 in Illinois and 8,000 in Pennsylvania.

Trump’s “smart” trade

action, then, might spark a trade war, hurt the auto industry, bleed jobs from

the Rust Belt and anger American allies around the world. A small number of

companies and workers stand to benefit, but a far larger number are now at

risk.

Of all the things to

say, this does not sound “easy.”