Who’s really to blame?

By Michael Schulson

Biswaroop Roy Chowdhury is an Indian engineer with, he says, an honorary Ph.D. in diabetes science from Alliance International University, a school in Zambia that bears many of the hallmarks of an online scam. He runs a small nutrition clinic near Delhi.

Biswaroop Roy Chowdhury is an Indian engineer with, he says, an honorary Ph.D. in diabetes science from Alliance International University, a school in Zambia that bears many of the hallmarks of an online scam. He runs a small nutrition clinic near Delhi. Two months ago, Chowdhury posted a brief video on YouTube arguing that HIV is not real, and that anti-retroviral medication actually causes AIDS. He offered to inject himself with the blood of someone who had tested positive.

Within weeks, the video had more than 380,000 views on YouTube. Tens of thousands more people watched on Facebook. Most of the viewers appear to be in India, where some 60,000 people die of HIV-related causes each year.

After the March video, Chowdhury kept on posting. Follow-up videos on HIV racked up hundreds of thousands more hits. He also distributed copies of an ebook titled “HIV-AIDS: The Greatest Lie of 21st Century.”

When I spoke with Chowdhury by phone last month, he claimed that 700 people had gotten in touch to say they had gone off their HIV medications. The actual number, he added, might be even higher. “We don’t know what people are doing on their own. I can only tell you about the people who report to us,” he said.

Chowdhury’s figures are impossible to verify, but his skills with digital media are apparent — as are the troubling questions they raise about the role of Silicon Valley platforms in spreading misinformation.

Such concerns, of course, aren’t new: Over the past two years, consumers, lawmakers, and media integrity advocates in the United States and Europe have become increasingly alarmed at the speed with which incendiary, inaccurate, and often deliberately false content spreads on sites like Facebook and YouTube — the latter a Google subsidiary.

Much of that concern has focused on hate speech, conspiracy theories, and fake political news. But the same questions apply to public health threats, too. Dubious — and potentially deadly — cures for autism have found sanctuary on social media for years, for example.

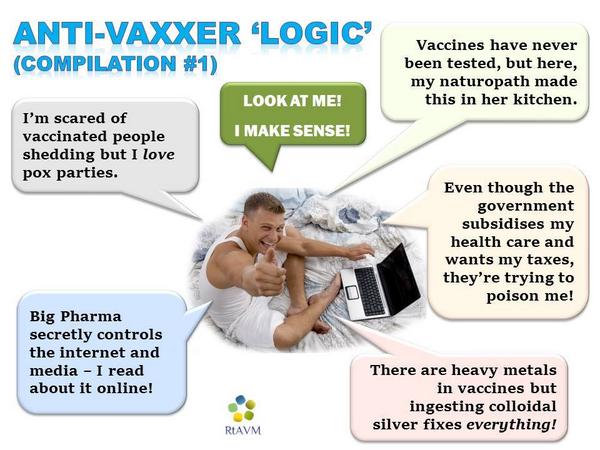

Desperate cancer patients have been lured online to baseless treatments peddled by shady "experts." And opponents of childhood vaccination thrive in an expanding and self-reinforcing internet bubble that researchers describe as "more real and more true" for its inhabitants than anything coming from the outside.

The question is, when content on social media and similar platforms nudges people toward dangerous medical decisions, do those websites bear any responsibility? And if so, how should they regulate such reckless speech?

These questions grow particularly stark with AIDS denialism. After all, convincing someone that the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and other U.S. sites was an inside job can make them sound a little whacky at parties. Convincing someone that AIDS is a hoax can kill them.

AIDS denialism, in the United States at least, emerged in at least the early 1990s, at a time of genuine uncertainty about human immunodeficiency virus and the causes of AIDS.

But even as the scientific evidence became clearer and treatments more effective, the notion that the disease is an elaborate hoax has persisted in some corners. Believers in this theory have launched nonprofits, held conferences, and produced documentaries.

In South Africa, where the country’s president in the late 1990s and 2000s came to believe many denialist theories, researchers have estimated that the resulting policies led to more than 330,000 deaths.

"What denialists are doing is basically interfering with the application of some highly effective, science-based treatments that have been developed over the last 30 some-odd years," said David Gorski, a surgical oncologist and the managing editor of Science-Based Medicine, a site that often challenges quackery. "So obviously there's a problem."

To some extent, the AIDS denialist movement had been on the wane in recent years — not least because many of its most prominent figures have died. Advances in modern medicine, too, have helped to blunt the movement's impact.

Seth Kalichman, a psychologist at the University of Connecticut and an expert on AIDS denialism, noted that treatment for HIV has made it possible to live an active life, for decades, with the disease — a testament to efficacy of treatment. “The facts of the common day person are becoming harder and harder to deny,” Kalichman told me.

Still, AIDS denialists have adapted readily to the internet age. “With each expansion of their technological soapbox, they have more reach,” Kalichman said over the phone. In an email to me, he was blunter. “Their visibility is increasing even as they become less and less relevant,” he wrote. “I think they are fizzling out and if not for social media, they’d probably have become a thing of the past.”

On YouTube, an account called Question Everything has racked up nearly 1.8 million views by posting documentaries, interviews with AIDS denialists, and other content.

A series of AIDS-skeptical videos produced in 2010 by RT, a Kremlin-funded, English-language news service, are also popular on YouTube. And then there are people like Chowdhury, whose low-budget content can quickly reach hundreds of thousands of viewers.

Peter Meylakhs, a researcher at the National Research University’s Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg, Russia, has studied how AIDS denialists organize on VK, Russia’s equivalent to Facebook. Whether in the U.S. or Russia, he told me, social media offers “a very low transactional cost of getting into the group of people with similar views.”

More worrying, though, is that the digital platforms that host such material and conversations aren’t always passive participants in the recruitment process.

Their algorithms, after all, are trained to give visitors more of the kind of content that they like — whatever that might be. While researching this column, for example, I started watching a lot of AIDS denialism videos on YouTube.

Immediately, the site began suggesting other denialist videos that I might want to watch, essentially serving up content to keep me on the site longer.

Had I been an HIV-positive YouTube user looking for answers about a troubling diagnosis, the effect, perhaps, would have been powerful. (Google did not respond to repeated requests for comment and chose not to answer a list of questions submitted by Undark).

YouTube also uses AIDS denialist videos to sell advertising space.

Here’s a screenshot of a commercial for the new Toyota Corolla, appearing before a video that claims that HIV tests are “extremely inaccurate” and medical therapies don’t work:

And here’s a screenshot of a Mercedes commercial that preceded an RT segment titled “The AIDS myth unraveled":

YouTube’s questionable medical content isn’t limited to AIDS denialism. YouTube videos are really a big deal,” said Gorski, adding that “it seems like every quack has his own series of YouTube videos.”

Denialist content spreads on Facebook, too. When Undark sent Facebook examples of AIDS denialist content on its site, including Chowdhury’s most popular HIV video, the company said that the content was not in violation of its policies. In an email, Lauren Svensson, a Facebook spokesperson, told Undark that the company recognizes that “contentious perspectives exist” on its platform.

“Counter-speech in the form of accurate information and alternative viewpoints can help create a safer and more respectful environment, and we have long believed that simply removing provocative thinking does little to build awareness around facts and approaches to health,” she wrote.

Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, internet platforms are immune from legal liability for most of the content they publish.

At the same time, companies like YouTube are allowed to police content on their sites as they deem appropriate, and videos like these could be seen as violations of YouTube’s own terms and conditions, which prohibit content “that intends to incite violence or encourage dangerous or illegal activities that have an inherent risk of serious physical harm or death.”

In at least one high-profile case, the site has taken down a channel that peddled questionable medical advice.

Do platforms, or even regulators, have a responsibility to police this sort of misleading or dangerous content more closely?

So far, European countries have been more willing than the United States to suppress certain kinds of misleading or even dangerous health information online. And in Russia, lawmakers have moved to outright ban AIDS denialist content.

The country is currently dealing with an HIV epidemic, and there are documented cases of HIV-positive children dying after their parents, skeptical of medical science, refuse to give them medication. But Meylakhs, the Russian scholar, worries that this kind of censoring strategy could backfire. “This will make them more martyr-like, and may, at least, increase their credibility,” he said.

Part of what makes this issue so complicated, perhaps, is the way that digital platforms bend some of our perceptions of both free speech and public space. Many Americans, steeped in First Amendment principles, for example, would defend a constitutional right for neo-Nazis to march down a public street, or for people to host a rally in a public park in order to promote a dangerous medical conspiracy theory. In one view, YouTube or Facebook simply offer a more high-tech version of that sidewalk or park.

But Facebook isn’t just offering a space for people to meet; its algorithms and search functions are helping them find each other. And YouTube isn’t just a neutral platform for incendiary content: It actively organizes it, and then algorithmically nudges people to view more of it. If a city government actually helped fringe groups put together mailing lists and distribute leaflets, citizens might, understandably, grow more suspicious.

With these and other nuances in mind, some scholars and advocates have begun arguing for more aggressive accountability for online platforms. “When there are clear examples of false … information that endanger individuals’ lives, that is when the platforms' responsibilities are at their apex, where they really have to start thinking deeply about their role and their responsibility in highlighting this stuff,” said Frank Pasquale, professor at the University of Maryland School of Law and a prominent critic of Silicon Valley policies.

Pasquale is skeptical of concerns that Silicon Valley platforms will wield too much power if they start declaring certain kinds of content off-limits. “They have the power already. The question is whether they're going to exercise that power responsibly, or are they going to hide behind algorithmic ordering, and just say, 'Well, it’s all algorithmic, it’s all done by some computer program in the sky, and we don’t really have responsibility for that,'” Pasquale said.

“But the amount of money they have — they clearly have enough money to support this type of intervention,” he added.

For now, platforms like YouTube fall into a gray space, somewhere between a public utility and a media company. The consequences of that ambiguity can unfold in places far from the American public eye. Chowdhury, the nutritionist in India, began posting YouTube videos in 2014. At the time, he told me, he was speaking to auditoriums about his cures, but he wanted to reach a larger audience, so he began filming his talks.

Today, his videos have been viewed close to 12 million times. One of them, about a purported cure for diabetes that does not require medicine, has more than three million views today on YouTube alone. He told me the site has never taken one of his videos down.

“I tried to go to the public through conventional media like television and newspapers,” Chowdhury said. “And I was shocked to know that they are really — even if I pay money — they are not ready … to cover my views, because my method goes opposite of that of conventional medical science.”

Chowdhury found the rules online to be far more forgiving.

“I prefer to go to YouTube,” he said. “I am happy.”

Michael Schulson is an American freelance writer covering science, religion, technology, and ethics. His work has been published by Pacific Standard magazine, Aeon, New York magazine, and The Washington Post, among other outlets, and he writes the Matters of Fact and Tracker columns for Undark.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.