By FRANK CARINI/ecoRI News staff

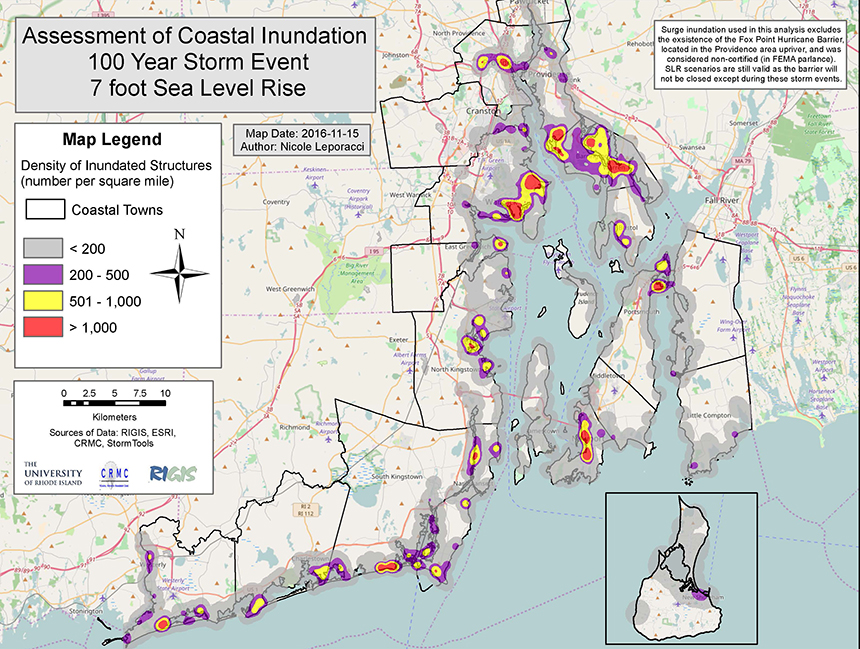

The Ocean State's 21 coastal communities have many structures that will be exposed to projected sea-level rise. (Beach SAMP)

When it comes to addressing the profound challenges presented by the Earth’s warming atmosphere, three words — “adaptation,” “mitigation” and “resilience” — are frequently deployed. But what do these buzzwords actually mean when it comes to addressing global warming in Rhode Island?

First, let’s define each of

the words.

Adaptation: “Adjustment

or preparation of natural or human systems to a new or changing environment

which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities,” Environmental

Protection Agency.

Mitigation: “Processes

that can reduce the amount and speed of future climate change by reducing

emissions of heat-trapping gases or removing them from the atmosphere,” U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

Resilience: “A

framework and principles to ensure that investments in climate change

adaptation are scientifically sound, socially just, fiscally sensible, and

adequately ambitious,” Union

of Concerned Scientists.

These words are used so

often and interchangeably — agencies even use the terms differently — that

their meanings have been diminished, as if simply uttering them addresses the

many challenges presented by climate change.

Grover Fugate, executive

director of Rhode Island’s Coastal

Resources Management Council (CRMC), calls resilience “the most

abused word in the English language. In the classic sense, it means the system

is robust enough to bounce back.”

In this era when we are

witnessing the climate change in mere decades instead of thousands of years,

thanks to building concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases, a bounce

back likely isn't in the cards. The system is closing in on collapse.

“We need to work toward mitigating

the effects of climate change so our children and grandchildren have a livable

world. The future depends on our behavior now,” said James Boyd, a CRMC coastal

policy analyst.

“The climate-change naysayers say we can fix this with carbon sequestration. They’re against zero-carbon energy. They want to use fossil fuels. The Earth is warming but we can fix that. We can’t. We can only slow it down. Even if we stopped carbon emissions today, sea-level rise is already baked into the system.”

“The climate-change naysayers say we can fix this with carbon sequestration. They’re against zero-carbon energy. They want to use fossil fuels. The Earth is warming but we can fix that. We can’t. We can only slow it down. Even if we stopped carbon emissions today, sea-level rise is already baked into the system.”

This chart and the one below are from Chapter 4 of the Beach SAMP.

A 2017

assessment from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration projects the baking to rise the waters off Rhode Island by 9.6

feet by 2100. By 2200, local sea-level rise is projected to be 32 feet.

As the ice sheets of the Arctic, Antarctic and Greenland disappear, this melt water won’t be uniformly distributed across the globe; the coasts of North America will be left to deal with much of it, for various scientific reasons, according to Fugate.

As the ice sheets of the Arctic, Antarctic and Greenland disappear, this melt water won’t be uniformly distributed across the globe; the coasts of North America will be left to deal with much of it, for various scientific reasons, according to Fugate.

Downtown Providence and

Wickford village in North Kingstown are at risk of significant damage from 3

feet of sea-level rise. Coastal roads in Narragansett and Jamestown are at risk

of being underwater with a foot of sea-level rise.

On Aquidneck Island, sea

level-rise maps of Newport’s waterfront, the heart of a thriving tourist

economy, reveal large swaths of harbor-side neighborhoods inundated and

prominent waterside landmarks partially submerged, all within an enlarged

harbor created by an additional 5 feet of sea. The Island Park neighborhood in

Portsmouth is among the most vulnerable areas in the state to storm surge and

sea-level rise.

Statewide, about $4.5 billion worth of property lies on land less than 5 feet above the high-tide line, and in Newport, for example, there is a 33 percent chance of a flood that high by 2040.

Rising seas also generate saltwater intrusion that can contaminate drinking-water supplies and private wells, damage septic systems, reduce the lifespan of asphalt, and threaten freshwater wetlands.

CRMC, a Wakefield-based

management agency with regulatory functions and a staff that includes coastal

geologists and engineers, is one of the leading agencies in the country when it

comes to addressing global warming. The agency has developed a number of

climate-change tools that model, project and educate, such as STORMTOOLS and Sea Level Affecting

Marshes Model (SLAMM).

The agency’s three special area management plans — Ocean SAMP, Beach SAMP and the still-in-development Metro Bay SAMP — are among a select few tools of their kind available to tackle climate-change issues. (California has a management plan that deals with sea-level rise.)

The U.S. Virgin Islands, New

Hampshire and California have all reached out to Fugate and CRMC to ask for

assistance in creating climate-change maps and tools.

ecoRI News recently met with

Fugate and Boyd to discuss Rhode Island’s climate-change challenges and how the

aforementioned climate strategies are and should be used to address local

problems.

Climate Adaptation

The Ocean State has about

420 miles of coastline that extends inland to include multiple waterways, most

notably Narragansett Bay. Shoreline types along the bay include vegetative

buffers and salt marshes, riprap, bulkhead and other hardened structures.

The bay’s shoreline also features disturbed areas, preserved marshland, post-industrial fill and polluting businesses. The bay’s working waterfront includes sites that store hazardous materials.

The bay’s shoreline also features disturbed areas, preserved marshland, post-industrial fill and polluting businesses. The bay’s working waterfront includes sites that store hazardous materials.

Sea-level rise, storm surge

and upland flooding in the Narragansett Bay watershed pose a considerable risk to

coastal municipalities along the bay, most notably Providence, Warwick, Warren

and Barrington.

“Amplification pushes surge

up into the bay where there’s less area for this water to go,” Fugate

explained. “Water is funneled up the bay.”

Rhode Island is part of an accelerated sea level-rise 'hot spot.'

(Beach SAMP Chapter 2)

He said sea-level rise of

5-7 feet would cover Providence’s downtown financial district and the Port of

Providence in water. This projected soggy future for downtown and ProvPort

doesn’t even take storm surge into consideration.

“The hurricane barrier is

not designed to protect the city from sea-level rise,” Fugate said. “It’s

designed to protect it from storm surge.”

Closed or open, sea-level

rise or storm surge, the Fox

Point Hurricane Protection Barrier does nothing to protect the

neighborhoods of South Providence and Washington Park from the toxins,

chemicals and pollutants buried in the dirt and hidden in the asphalt and

concrete of the city’s working waterfront.

The Port of Providence

serves as a coal port, a fuel-oil depot, and a train depot for ethanol. It’s

also home to several chemical-processing plants, including a facility that

manufactures chemicals for hydraulic fracturing.

The area proposed for a

second waterfront LNG facility is heavily contaminated. The 42-acre site on the

Providence River has endured more than a century of pollution. It once hosted

an Army rifle range, a coal gasification plant, and propane and kerosene

storage facilities.

Should this area be flooded

by sea-level rise or storm surge associated with a hurricane like the one Rhode

Island witnessed in 1954 — a 100-year event, according to Fugate, meaning it

has a 1 percent chance of happening annually — or 1938, a 250-year event, those

two neighborhoods would be soaked with some serious

nastiness.

Not all of the Ocean State’s

21 coastal communities, however, are along the shores of Narragansett Bay.

Many, such as Charlestown, Narragansett and Westerly, are on the open ocean and that presents a different set of climate-change problems, like accelerating erosion.

For instance, along the state’s more exposed southern shoreline in communities from Point Judith to Watch Hill, Matunuck, Misquamicut and South Kingstown Town Beach have lost some 400 feet of beach combined during the past four decades.

Many, such as Charlestown, Narragansett and Westerly, are on the open ocean and that presents a different set of climate-change problems, like accelerating erosion.

For instance, along the state’s more exposed southern shoreline in communities from Point Judith to Watch Hill, Matunuck, Misquamicut and South Kingstown Town Beach have lost some 400 feet of beach combined during the past four decades.

Charlestown Town Beach has

lost about 150 feet to erosion since 1939. Two of Rhode Island’s more popular

tourist destinations, Easton’s Beach in Newport and Sachuest Beach in

Middletown, are losing about a foot of shoreline annually.

Saltwater marshes, nature’s

protector against storm surge, are already drowning.

Percent chance of flooding for a given return period and a given

number of years. (Beach SAMP Chapter 3)

If someone were to buy a waterfront home in Rhode Island today with a typical 30-year mortgage, there is a 26 percent chance a 100-year storm would hit during the life of that mortgage.

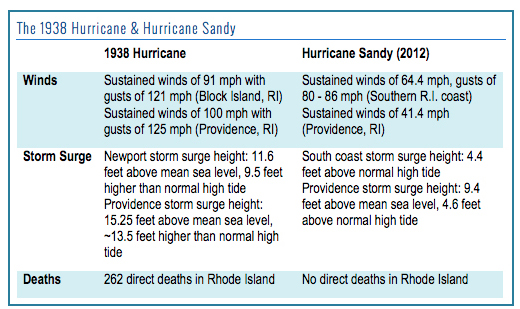

The damage caused in fall

2012 by Sandy highlighted the vulnerability of the state’s coastal areas to the

effects of worsening storms and a changing climate.

When Sandy hit Rhode Island

in late October, it was barely a tropical storm, but it hung around for so long

that it caused big problems. Sandy’s storm surge was 5 feet lower than that of

the 1938 hurricane, but it still caused a lot of damage — an estimated $42

million in Rhode Island recovery costs.

The so-called superstorm

stripped some 1,600 tons of sand from Narragansett Town Beach and dumped about

18,000 tons onto Atlantic Avenue in Westerly.

In Charlestown, more than 4 feet of sand wound up on Charlestown Beach Road. Storm waves tossed boulders around like beach balls along the Charlestown Breachway.

In Charlestown, more than 4 feet of sand wound up on Charlestown Beach Road. Storm waves tossed boulders around like beach balls along the Charlestown Breachway.

In all, the Ocean State lost

about 90,000 cubic yards of beach sand because of Sandy’s rude visit.

As the burning of fossil

fuels continue to warm the oceans, Rhode Island will experience a growing

number of more intense storms that drop more and more precipitation, according

to Boyd. The March 2010 floods were an early example.

He noted that Houston has

experienced 500-year weather events three times in the past five years,

including Hurricane Harvey last year. Ellicott City in Howard County, Md., has

experienced 1,000-year events twice in the past three years.

Adaptation examples: Relocating

buildings out of floodplains or further inland from rising seas; planting

vegetation with high salt tolerance that are capable of rapid establishment can

help prevent coastal erosion; growing a variety of native plants to promote

healthy habitats; using less water during times of drought.

R.I. efforts: Rhode

Island Shoreline Change Special Area Management Plan (Beach SAMP) was created

to bring state, federal, municipal, academic and private-sector interests

together to create a plan to help communities adapt to short-term and long-term

shoreline change.

Since the flooding of March 2010, Cranston has been buying houses and tearing them down, as some 20 homes in flood-prone neighborhoods along the Pawtuxet and Pocasset rivers have been razed and the lots reclaimed by nature.

University of Rhode Island researchers are studying key areas to understand how the coast has changed, what it may look like in the future, and what infrastructure is at risk; the state’s coastal construction setback program requires commercial properties to be set back 60 times the erosion rate.

Allowing some beaches to do what they want to do naturally, as Black Point in Narragansett, East Beach in Charlestown and Quonochontaug Beach in Westerly are doing fine on their own.

Some buildings along the Westerly coast have been moved 30 or so feet back, others are being built higher off the ground and nearly 200 beach parking spaces have been removed to create a bigger coastal buffer.

CRMC is developing Rhode Island flood-zone maps that are more accurate than the ones currently offered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Since the flooding of March 2010, Cranston has been buying houses and tearing them down, as some 20 homes in flood-prone neighborhoods along the Pawtuxet and Pocasset rivers have been razed and the lots reclaimed by nature.

University of Rhode Island researchers are studying key areas to understand how the coast has changed, what it may look like in the future, and what infrastructure is at risk; the state’s coastal construction setback program requires commercial properties to be set back 60 times the erosion rate.

Allowing some beaches to do what they want to do naturally, as Black Point in Narragansett, East Beach in Charlestown and Quonochontaug Beach in Westerly are doing fine on their own.

Some buildings along the Westerly coast have been moved 30 or so feet back, others are being built higher off the ground and nearly 200 beach parking spaces have been removed to create a bigger coastal buffer.

CRMC is developing Rhode Island flood-zone maps that are more accurate than the ones currently offered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Climate Mitigation: Climate-change mitigation

basically comes down to reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, which are trapping

heat and warming the atmosphere. But even if humans stopped emitting all

greenhouse gases today, as Boyd noted when it comes to sea-level rise, the Earth’s

atmosphere would still need time to “digest” all the extra carbon dioxide and

methane.

Climate change is directly

linked to human activity, overpopulation and consumption. The many challenges

to mitigating the impacts of a changing climate are closely tied to

environmental protections, public health, public transportation, land use, and

social justice.

Brown University professor

Timmons Roberts has noted that Rhode Island's goal of cutting carbon dioxide

emissions 80 percent by 2050 isn’t sufficient to slow the effects of climate

change. The latest research, he says, suggests human-caused greenhouse-gas

emissions must be cut to zero by 2035.

The Rhode Island Executive

Climate Change Coordination Council (EC4) is the best entity to lead

emission-reduction action, according to Roberts, who serves on an EC4

subcommittee. But he says the council of state agency bosses is moving too

slowly. He has criticized the EC4’s 2016 analysis of

the state emission plan for failing to advocate for a proposal to achieve the

carbon reductions.

“It wasn’t actually a plan.

It doesn’t really tell us how we are going to get there. It lacks the social

and the political and economic steps we can make and the policy tools at the

economy-wide level,” Roberts said during a May

2017 panel discussion in Providence.

This chart and the one below are from Chapter 4 of the Beach SAMP.

Political support for the proposed Clear River Energy Center in Burrillville won’t help mitigate local climate-change impacts. If built, the facility would become Rhode Island’s largest fossil-fuel power plant and the largest emitter of greenhouse-gas emissions in the state.

To mitigate the impacts of

global warming, Rhode Island’s focus, incentives and political support need to

be fixated on carbon-neutral energy sources such as solar, wind and tidal

power.

“The Earth’s history has seen huge swings in sea levels because of a changing climate, but the planet hasn’t seen this concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide in three million years,” Boyd said. “The system used to have tens of thousands of years to adjust. Now we’re creating changes in a matter of decades.”

The current atmospheric

concentration of CO2 is 411 parts per million.

In fact, last year was the first in many to see a jump in carbon emissions

worldwide.

Mitigation examples: Plant

trees which absorb carbon dioxide; replace incandescent lights with compact

fluorescent bulbs that use less electricity; improve energy efficiency;

modernize power grids; better use of public transportation; increased landfill

methane recovery.

R.I. efforts: Rhode

Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP) was created to help

Rhode Island and the Northeast make wise choices for long-term enhancement of

shared ocean resources, including offshore renewable-energy siting; Block

Island Wind Farm; Central Landfill in Johnston hosts one of the largest

landfill-gas power plants east of the Mississippi River and is the state’s

largest producer of renewable energy; Rhode Island is a member of the

nine-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative; continued efforts to get a

carbon-tax bill approved.

Climate Resilience

This summer, Rhode Island’s

first comprehensive climate preparedness strategy, Resilient Rhody,

is expected to be released. To ensure a common understanding of climate

resilience, project participants adopted a definition to align with Rhode

Island priorities: “Climate resilience is the capacity of individuals,

institutions, businesses, and natural systems within Rhode Island to survive,

adapt, and grow regardless of chronic stresses and weather events they

experience.”

Rhode Island’s definition

doesn’t exactly align with the one adopted by the Union of Concerned

Scientists. In fact, growth — of the human population, of natural resource

consumption — is what feeds climate change.

Adequately addressing global

warming's tangle of environmental, societal and economic impacts is no easy

task. Sacrifice is part of the solution. Growth is not. There are no solutions

that require zero sacrifice and embrace growth.

While Sandy caused significant damage, the 1938 hurricane eclipsed

the 2012 storm in wind speed, height of storm surge and overall strength.

Furthermore, coastal development has reclaimed much of the land area impacted by

the ’38 storm, so even more property, assets and infrastructure will be at risk

should a 100-year-storm hit Rhode Island directly. (CRMC)

The hope with Resilient

Rhody is that it doesn’t end up being a political tool strategically unveiled

before an election. Most of Rhode Island’s environment-related state reports,

guides and plans are celebrated, filed away and then ignored as the local

inequality chasm widens and the Ocean State’s natural world is chewed up.

From the outside — this

reporter did participate in one of the 10 “Resiliency Roundtables” held

statewide to help craft the plan — Resilient Rhody appears to be a hastened

attempt to address a serious issue: an overworked state employee given less

than a year and very limited funding to identify “projects, policies and

legislation, or funding and financing opportunities that the state can take to

better prepare for a changing climate.”

One climate-related issue

Rhode Island is already well focused on is the vulnerability of wastewater

treatment plants, as increasingly intense storms have damaged such facilities

and pump stations, which are typically located in low-lying areas.

Of the state’s 19 major

treatment facilities, seven are predicted to become predominantly inundated in

a catastrophic event, according to a Rhode Island

Department of Environmental Management study.

“Warren, to its credit, is

discussing a new location for its sewage treatment plant,” Fugate said. “That’s

what is needed — a change in thinking.”

The Rhode Island Department

of Health (DOH) is studying vector-borne diseases associated with a warming and

wetter local climate and educating the public about the growing problem.

Between 2016 and 2017, Rhode

Island saw a 22 percent increase in the number of cases of Lyme disease

reported by health-care providers to the DOH. Earlier this month, the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention issued a report stating

that the number of cases of diseases that are transmitted by ticks, mosquitos

and other insects more than tripled between 2004 and 2016.

“We’re not doing enough yet

to address the impacts of climate change, but we have the information to make

the necessary moves,” Fugate said. “It takes leadership."

Resilience examples: Multi-stable

socio-ecological systems; smart growth; low-impact development; planning that

accounts for both acute events such as heavy rains, hurricanes and wildfires

that will become more frequent and intense as the climate changes and for

chronic events such as rising sea levels, worsening air quality and population

migration; regional wastewater treatment facilities.

R.I. efforts: PREP-RI online module series helps

municipal decision-makers make effective choices supporting resilience to the

impacts of climate change; Rapid

Property Assessment and Coastal Exposure (Rapid PACE) helps

local officials and property owners view areas exposed to coastal hazards;

lauded renewable-energy programs.