Trump’s Lawyers Insist

He’s Above the Law; He Says He Can Pardon Himself

The

letter from President Trump’s lawyers to Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III

published last weekend is a legal outline for overturning our democracy.

The

letter from President Trump’s lawyers to Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III

published last weekend is a legal outline for overturning our democracy.It is a quiet rejection of our Constitution and our basic belief that all are considered equal in the eyes of the law. And the argument is being thrown around as a weapon of sorts to gain personal privilege for the president, a red carpet pardon for anything that this individual has done and may ever do.

In reading through the letter, written in January but first published by The New York Times, there is a simply disturbing sense that in vigorously seeking to defend their client, lawyers for the president cannot be forced to testify in the all-things-Russia inquiry.

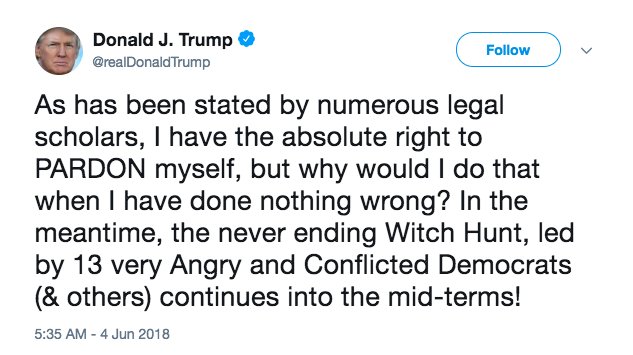

They assert that as president, Trump has absolute power to stop any federal inquiry, ignore it, or simply pardon all concerned, presumably including himself.

As commented Ruth Marcus of The Washington Post: “L’etat, c’est Trump. For months we’ve heard President Trump’s TV lawyers, as he calls them, bandy about the argument that he—or any president, for that matter—couldn’t have obstructed justice because justice is what he says it is.”

Despite political chasms in this country, perhaps we can agree, we don’t really know whether the Mueller investigation has the evidence to prove a crime or crimes occurred, or who exactly committed them.

|

| 5:30 AM: why doesn't he borrow an Ambien from Roseanne Barr? |

Most of the indictments to date have involved lying to the FBI rather than the substantive issues. Nevertheless, arguing that the president can’t be held accountable because he is the president seems to cross a constitutional line for me.

Let’s skip the idea that such an argument would never hold against a political foe to these particular lawyers.

To see Rudy Giuliani, who did not write this memo but who has picked up on the central themes, excitedly argue that no one has the legal ability to question this president strikes me as legally outrageous. Indeed, Giuliani argues on television that this president has the perfect right to pardon himself.

It’s absurd as law and as American tradition. I would also argue that this is not good politics either.

For openers, former President Bill Clinton was well on his way toward losing this legal point when he accepted the idea of questioning, and his legal team settled for negotiating the conditions under which the questions would be asked—in a much more straightforward, legally simple set of issues.

There will be plenty of time for Trump’s legal team to dispute whether any charges should be issued as a result of the investigation—and any potential questioning.

There will be plenty of time and political cover for Congress to discuss any potential actions to pursue. But to eliminate the idea that the president needs to answer questions about his own actions, to say nothing of the actions of his campaign, defies legal logic.

Indeed, though Special Counsel Mueller stays Sphinx-like quiet throughout such incidents, Mueller should call Trump’s bluff. If Trump does not volunteer to take part in an on-the-record conversation with Mueller’s team, Mueller should seek a grand jury subpoena for the president.

None of this can be good for the country. The increasing hostility over whether the president can be forced to answer questions will tear at the country’s political divide. But not doing so will also tear at the country’s unity.

What principle do Americans hold more central than equality before the law? It means that no one—not even the president—can hold himself above the law, even if it is terribly uncomfortable.

He is a president, working for us, the American people, and not a king or autocrat. He ought to act as such. He is a president of a divided country, and ought to be putting country first, not himself. He is an avowed “populist,” yet relies on the trite trappings of wealth and personal power.

The idea that Trump’s legal team fears most that Trump will trip himself up during such questioning, opening himself to possible perjury charges or other legal complications just shows why these questions are obvious and important for the president to answer.

Whether Trump committed obstruction of justice in firing former FBI director James B. Comey Jr. may well depend on a judgment call about the president’s intent. The best way to get to that intent is to ask the president what he had in mind.

Even if Mueller concludes that there was obstruction of justice, that may not result in the indictment of a president while in office. It could well result in a political process that puts the question before a Republican-dominated Congress, which has shown a remarkable spryness at finding ways to protect the president.

The rest of us cannot stop investigations or fire the investigators or refuse based on our standing in society. If the authorities think I have robbed a bank, they are going to question me and mine, and nothing I say will be able to stop that. Finally, of course, there will be a forum to dispute the allegations, but I cannot stop the idea of investigating.

The president and all of his men are on full-time duty undermining the validity of the special counsel investigation—apparently with success, at least for the president.

But none of this helps to understand whether Russia did try to influence our elections using Trump campaign contacts as willing helpers.

None of this helps to understand whether our president is spending his time slipping and sliding around legally questionable tactics towards stopping any inquiry.

None of this responds to the myriad financial, ethical, foreign contact, and business entanglements that have marked the Trump circle in its dealings with Russians in particular and foreigners in general.

The letter from the lawyers is a remarkable distillation of the thinking that Trump is to be held above any reproach for anything at any time.

It is an insulting threat to democracy, and Mueller—and the courts—should treat it as such.