By FRANK CARINI/ecoRI

News staff

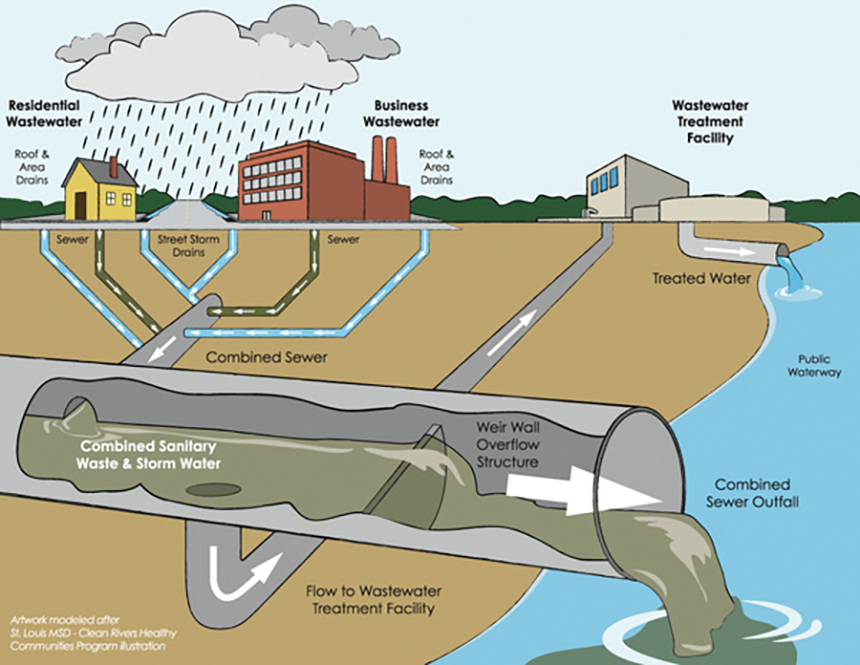

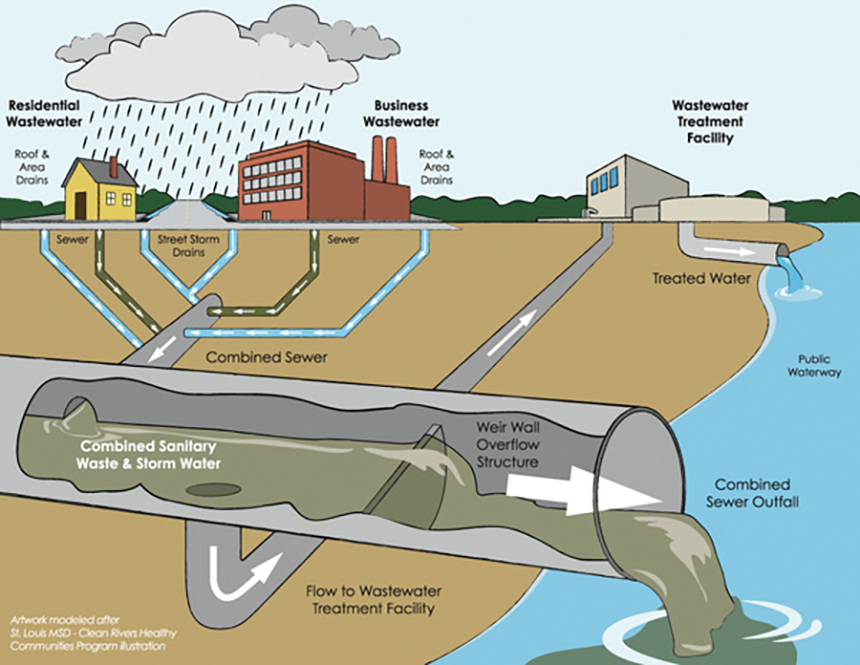

The use of sewer, highlighted above, and septic systems to deal with human waste generate pollution and wastewater. Septic systems leak waste into groundwater, which can contaminate onsite drinking-water wells or other nearby wells. (Moss Design)

Today’s composting

toilets are not the equivalent of a port-a-potty stashed away in the basement.

In fact, some models look similar to everyday commodes, but they all save water

for drinking and showering.

And they don’t stink, require chemicals to clean, or flush or discharge human waste into the natural environment.

And they don’t stink, require chemicals to clean, or flush or discharge human waste into the natural environment.

The average

single-family home in the United States uses about 88,000 gallons of water

annually, according to a 2016 study. Some 24

percent of the daily usage, or about 30 gallons, is flushed down the toilet.

Despite federal regulations requiring that toilets use only 1.6 gallons of water per flush, toilets made before 1992 may be using up to 7 gallons a flush.

Even with the reduced 1.6-gallon standard, however, a single toilet flushed five times a day will waste nearly 2,340 gallons of potable water annually.

“Unfortunately we don’t

price or value water the way we should,” said Conor Lally, an ecological

sanitation planner and installer with a background in watershed science and

ecological design.

“Composting toilets just make more sense because you are not creating that wastewater to begin with. It’s a better way of managing that material.”

“Composting toilets just make more sense because you are not creating that wastewater to begin with. It’s a better way of managing that material.”

The Providence resident

and New York native co-founded Nutrient Networks to

focus on “root cause solutions to the economic and environmental problems

associated with conventional water, wastewater, and food systems.”

Those behind this fairly

new endeavor, including co-founder Danilo Morales and composting toilet guru

and vermicomposter Ben Goldberg, design, build, and install

composting and management systems that divert valuable nutrients from the waste

stream, reduce pollution, and help close the food-nutrient cycle.

They believe such

efforts play a critical role in the larger movement toward localizing energy,

water, and food, building soils, and improving public health.

Treating human waste

with septic systems and wastewater treatment plants is costly in both energy

and resources, contributes to soil and water pollution, contaminates

drinking-water supplies, and leads to combined sewage overflows into important

water bodies.

As the human population

continues to increase — 7.6 billion and counting — planners and

public-health professionals are beginning to recognize the need for

environmentally sound human waste treatment and recycling methods.

The notion of converting human waste to a usable resource, however, isn’t a new concept.

The notion of converting human waste to a usable resource, however, isn’t a new concept.

Wasting a resource

Lally’s first job out of college — he graduated from Boston University with a master’s degree in energy and environmental analysis — was working for John Todd Ecological Design doing constructive wetlands for wastewater treatment in Woods Hole on Cape Cod. His interest soon shifted to dry sanitation and composting toilets. He began working with Goldberg.

Lally’s first job out of college — he graduated from Boston University with a master’s degree in energy and environmental analysis — was working for John Todd Ecological Design doing constructive wetlands for wastewater treatment in Woods Hole on Cape Cod. His interest soon shifted to dry sanitation and composting toilets. He began working with Goldberg.

Lally said Todd’s

ecologically designed wastewater treatment systems still have a place, “but

what we started to realize was it was a smarter way of doing a stupid thing,

because at the end of the day we were still facilitating people pooping in

their drinking water.”

“It was a sexier way of

cleaning it up, but at the basis of it still was maybe not the best option, so

I became more interested in not creating the problem to begin with,” he

continued. “I think that’s what composting toilets and ecological sanitation is

all about.”

|

| A composting toilet at Crane Beach in Ipswich, Mass. (Clivus New England) |

Originally

commercialized in Sweden, composting toilets have been an established

technology for more than three decades, but there’s still plenty of hesitation

when it comes to installing one in a home or making them part of 21st-century

building codes.

In fact, one of the major obstacles holding back composting toilet use in the United States are regulations geared toward flush systems and their waste of water.

In fact, one of the major obstacles holding back composting toilet use in the United States are regulations geared toward flush systems and their waste of water.

Composting toilet

systems — sometimes called biological toilets, dry toilets, or waterless toilets

— contain and control the composting of human waste and toilet paper.

And, unlike a septic system, composting toilets rely on aerobic bacteria to break down wastes, just as they do in a backyard compost pile.

And, unlike a septic system, composting toilets rely on aerobic bacteria to break down wastes, just as they do in a backyard compost pile.

Lally said the next step

for ecological sanitation is taking it to the watershed scale or community

scale to have a broader positive impact on the environment, most notably on

water bodies.

“That hasn’t necessarily

happened yet, but that’s what we are hoping to do,” he said. “To kind of make

the next jump with all of this.”

Nutrient Networks

travels across New England installing residential composting toilets and

designing and building more complex wastewater systems.

The company, for instance, has installed two composting toilets at the Listening Tree Cooperative in Chepachet, R.I., and seven at Round the Bend Farm in South Dartmouth, Mass.

The company, for instance, has installed two composting toilets at the Listening Tree Cooperative in Chepachet, R.I., and seven at Round the Bend Farm in South Dartmouth, Mass.

Lally has also traveled

to New Zealand and the Grand Canyon to work on ecological sanitation projects.

The state of Rhode

Island installed its first composting toilet during a major renovation of the

Misquamicut State beach pavilion in the 1990s. Today, there are more than 20 composting

toilets at state parks, beaches, and campgrounds.

Shoveling humanure

Composting toilets only treat human waste, so a separate wastewater system, either a septic tank or sewer hookup, is needed to handle dish washing, laundry, and bathing.

Composting toilets only treat human waste, so a separate wastewater system, either a septic tank or sewer hookup, is needed to handle dish washing, laundry, and bathing.

Composting toilets can

be retrofitted into an existing bathroom or incorporated into new construction.

They come in many shapes and sizes depending upon the number of users. They can

be homemade, custom-built, or manufactured.

The way they work isn’t

“dissimilar from your backyard composting,” Lally said. “It relies on the same

science, but there is the element of potential pathogens that has to be taken

seriously. But with enough retention time it can produce a very safe,

nutrient-rich compost that can be worked back into the soil rather than flushed

out into our water bodies.”

He said maintenance of

most systems isn’t difficult or time consuming, but “very important to do.”

The most important thing

when selecting a composting toilet is to choose a system that adequately meets

your home or business needs, according to Goldberg, who has been installing

composting toilet systems in private residences, businesses, and public

facilities across New England since the 1980s.

Lally noted model and

system choices come down to preferences.

“There’s a lot of

different systems out there so someone might be more interested in being more

engaged and want to actually have a very simple bucket-style system where they

are more frequently bringing a bucket of humanure out to a secondary compost

site,” he said. “Other people might not have any interest in having that level

of involvement in managing their own humanure.”

He said some of

the more advanced, large-capacity systems such

as the Phoenix and Clivus Multrum have very simple maintenance tasks and

everything happens within a basement tank. Regular management of most

composting toilet systems requires adding carbon-based bulking material such as

pine shavings or saw dust.

“I think it’s good for

people to be a little bit more aware and engaged in how humanure can be

managed,” Lally said. “We see it as a resource not as a waste.”