by Jesse Eisinger for ProPublica

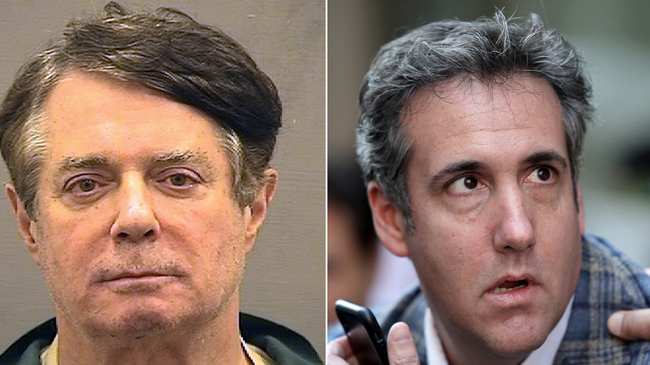

But how anomalous are Mssrs. Manafort and Cohen? Are there legions of K Street big shots working for foreign despots and parking their riches in Cypriot bank accounts to avoid the IRS? Are many political campaigns walking felonies waiting to be exposed? What about the world of luxury residential building in which Cohen plied his trade with the Trump Organization?

The answer is more disturbing than the questions: We don’t know.

We don’t know because the cops aren’t on the beat. Resources have been stripped from white-collar enforcement. The FBI shifted agents to work on international terror in the wake of 9/11.

White-collar cases made up about one-tenth of the Justice Department’s cases in recent years, compared with one-fifth in the early 1990s. The IRS’ criminal enforcement capabilities have been decimated by years of budget cuts and attrition. The Federal Election Commission is a toothless organization that is widely flouted.

No wonder Cohen and Manafort were so brazen. They must have felt they had impunity.

How could they not? Any person in any bar in America can tell you who was held accountable for the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, which peaked 10 years ago next month: No one. No top officer from any major bank went to prison.

But the problem goes beyond big banks. The Department of Justice — in both Democratic and Republican administrations — has lost the will and ability to prosecute top executives across corporate America, at large industrial firms, tech giants, retailers, drug makers and so on.

Instead the Department of Justice reaches settlements with corporations, which pay in dollars instead of the liberty of their top officers and directors.

Beginning with a charge to investigate Russian interference in the 2016 election, special counsel Robert Mueller has fallen upon a rash of other crimes. In doing so, he has exposed how widespread and serious our white-collar fraud problem really is, and how lax enforcement has been for years.

At least he is also showing a way out of the problem. He and his team are demonstrating that the proper attention, resources, technique and experience can go a long way to rectify the white-collar prosecution crisis.

What’s Mueller’s secret? For one thing, he has a focus. He and his team have sufficient resources to go after a discrete set of investigations. In the early 2000s, the Justice Department had similar success setting up the Enron Task Force, a special SWAT team of government lawyers that prosecuted top executives of the failed Texas energy trader.

That contrasts with the financial crisis, when the Justice Department never created a similar task force. No single department official was responsible for the prosecutions of bankers after the global meltdown.

The investigation’s techniques are also instructive. The Southern District of New York, which was referred the Cohen case by Mueller, raided President Trump’s former attorney’s offices and fought for access to the materials, even as Cohen asserted attorney-client privilege. When federal prosecutors investigate large companies, out of custom and deference they rarely use such aggressive tactics.

They place few wiretaps, conduct almost no undercover operations and do almost no raids. Instead government attorneys reach carefully negotiated agreements about which documents they can review, the product of many hours of discussion with high-powered law firms on behalf of their clients.

All the battles over privileged materials happen behind closed doors and without the benefit of a disinterested special master, as the Cohen case had.

Indeed it’s worse than that. The government has essentially privatized corporate law enforcement. The government effectively outsources the investigations to the companies themselves. The companies, typically trying to appear cooperative or to forestall government action, hire law firms to do internal investigations. Imagine if Mueller relied on Trump to investigate whether he colluded with the Russians or violated any other laws, and Trump hired Rudy Giuliani’s firm to do the probe.

The aggressive Mueller techniques have yielded the most crucial element for white-collar cases: flippers; i.e., wrongdoers who agree to testify against their co-conspirators. Rick Gates, the Manafort protégé, helped tighten his mentor’s noose. We are going to see in the next few months how many people flip and what they will say. No wonder President Trump mused that flipping “almost ought to be illegal.”

Mueller’s experience has given him the courage to take cases to trial, where juries are mercurial and the federal bench has turned hostile. Mueller’s prosecutors tried a “thin case” against Manafort, as the expression goes, boiling their evidence down to a few elements that the jury could absorb easily.

They even managed to overcome the open hostility of U.S. District Court Judge T.S. Ellis. Good prosecutors are used to that in white-collar cases. Judges and justices have not looked favorably upon white-collar prosecutions for more than a decade now, overturning verdicts and narrowing statutes.

But with well-marshaled evidence and clear presentation, prosecutors can surmount the difficulties.

Moreover, Mueller isn’t looking to go soft in order to preserve his professional viability. I’m assuming that at age 74, he’s not going to go through the revolving door after this.

That hasn’t been true for most top Justice Department officials in recent years. Many of them come from the defense bar and when they leave government they go back to defending large corporations. The same goes with the younger prosecutors who negotiate those corporate settlements.

Almost all go on to become corporate defense attorneys. In those negotiations, they are auditioning for their next jobs, wanting to display their dazzling smarts but also eventually needing to appear like reasonable people and avoid being depicted by the white-collar bar as cowboys unworthy of a prestigious partnership.

Of course, we don’t know whether Mueller can go all the way to the top. The big issue in white-collar crime is whether the Justice Department can prosecute CEOs. Sure, it occasionally brings charges against lower-level executives of major corporations, but hasn’t held the chief of a Fortune 500 company accountable in more than a decade.

While most observers believe Mueller will adhere to policy and not indict the president, will his report to Congress implicate the chief executive of the United States, if the evidence warrants it?

One man cannot fix the large problem on his own, however. “For these individual episodic financial crimes, the government can muster the capacity and courage to investigate and prosecute,” says Paul Pelletier, a former federal prosecutor who recently ran for Congress in a Democratic primary.

“The real question is whether, in the context of a national economic crisis, the Department of Justice has sufficient experience, resources and leadership to effectively tackle it. I’d argue that it’s pretty obvious it does not.”

For that, the Justice Department requires more resources and bodies than the government devotes to white-collar crime today, and probably some changes in the law.

Nevertheless, this should be a moment of reflection for white-collar prosecutors. It should not take a special counsel to uncover millions in bank fraud, money laundering and tax evasion. Using proper techniques, prioritizing crimes that can harm millions of people and stiffening their obsequious posture toward corporate executives will go a ways to remedying the situation.

Here’s the bad news, which will be the least surprising thing you’ll read today: the Trump administration is moving in the opposite direction.

Its law enforcement agencies are engaged in something of a regulatory strike, especially when it comes to white-collar enforcement.

Regulators are not policing companies or industries and are not referring cases to the Justice Department. The number of white-collar cases filed against individuals is lower than at any time in more than 20 years, according to research done by Syracuse University. The Justice Department’s fines against companies fell 90 percent during Trump’s first year in office, compared with in Obama’s last year in office, according to Public Citizen.

That must be sweet music to not just to other Manaforts and Cohens but also any corporate malefactors out there.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for their newsletter.

The answer is more disturbing than the questions: We don’t know.

We don’t know because the cops aren’t on the beat. Resources have been stripped from white-collar enforcement. The FBI shifted agents to work on international terror in the wake of 9/11.

White-collar cases made up about one-tenth of the Justice Department’s cases in recent years, compared with one-fifth in the early 1990s. The IRS’ criminal enforcement capabilities have been decimated by years of budget cuts and attrition. The Federal Election Commission is a toothless organization that is widely flouted.

No wonder Cohen and Manafort were so brazen. They must have felt they had impunity.

How could they not? Any person in any bar in America can tell you who was held accountable for the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, which peaked 10 years ago next month: No one. No top officer from any major bank went to prison.

But the problem goes beyond big banks. The Department of Justice — in both Democratic and Republican administrations — has lost the will and ability to prosecute top executives across corporate America, at large industrial firms, tech giants, retailers, drug makers and so on.

Instead the Department of Justice reaches settlements with corporations, which pay in dollars instead of the liberty of their top officers and directors.

Beginning with a charge to investigate Russian interference in the 2016 election, special counsel Robert Mueller has fallen upon a rash of other crimes. In doing so, he has exposed how widespread and serious our white-collar fraud problem really is, and how lax enforcement has been for years.

At least he is also showing a way out of the problem. He and his team are demonstrating that the proper attention, resources, technique and experience can go a long way to rectify the white-collar prosecution crisis.

What’s Mueller’s secret? For one thing, he has a focus. He and his team have sufficient resources to go after a discrete set of investigations. In the early 2000s, the Justice Department had similar success setting up the Enron Task Force, a special SWAT team of government lawyers that prosecuted top executives of the failed Texas energy trader.

That contrasts with the financial crisis, when the Justice Department never created a similar task force. No single department official was responsible for the prosecutions of bankers after the global meltdown.

The investigation’s techniques are also instructive. The Southern District of New York, which was referred the Cohen case by Mueller, raided President Trump’s former attorney’s offices and fought for access to the materials, even as Cohen asserted attorney-client privilege. When federal prosecutors investigate large companies, out of custom and deference they rarely use such aggressive tactics.

They place few wiretaps, conduct almost no undercover operations and do almost no raids. Instead government attorneys reach carefully negotiated agreements about which documents they can review, the product of many hours of discussion with high-powered law firms on behalf of their clients.

All the battles over privileged materials happen behind closed doors and without the benefit of a disinterested special master, as the Cohen case had.

Indeed it’s worse than that. The government has essentially privatized corporate law enforcement. The government effectively outsources the investigations to the companies themselves. The companies, typically trying to appear cooperative or to forestall government action, hire law firms to do internal investigations. Imagine if Mueller relied on Trump to investigate whether he colluded with the Russians or violated any other laws, and Trump hired Rudy Giuliani’s firm to do the probe.

The aggressive Mueller techniques have yielded the most crucial element for white-collar cases: flippers; i.e., wrongdoers who agree to testify against their co-conspirators. Rick Gates, the Manafort protégé, helped tighten his mentor’s noose. We are going to see in the next few months how many people flip and what they will say. No wonder President Trump mused that flipping “almost ought to be illegal.”

Mueller’s experience has given him the courage to take cases to trial, where juries are mercurial and the federal bench has turned hostile. Mueller’s prosecutors tried a “thin case” against Manafort, as the expression goes, boiling their evidence down to a few elements that the jury could absorb easily.

They even managed to overcome the open hostility of U.S. District Court Judge T.S. Ellis. Good prosecutors are used to that in white-collar cases. Judges and justices have not looked favorably upon white-collar prosecutions for more than a decade now, overturning verdicts and narrowing statutes.

But with well-marshaled evidence and clear presentation, prosecutors can surmount the difficulties.

Moreover, Mueller isn’t looking to go soft in order to preserve his professional viability. I’m assuming that at age 74, he’s not going to go through the revolving door after this.

That hasn’t been true for most top Justice Department officials in recent years. Many of them come from the defense bar and when they leave government they go back to defending large corporations. The same goes with the younger prosecutors who negotiate those corporate settlements.

Almost all go on to become corporate defense attorneys. In those negotiations, they are auditioning for their next jobs, wanting to display their dazzling smarts but also eventually needing to appear like reasonable people and avoid being depicted by the white-collar bar as cowboys unworthy of a prestigious partnership.

Of course, we don’t know whether Mueller can go all the way to the top. The big issue in white-collar crime is whether the Justice Department can prosecute CEOs. Sure, it occasionally brings charges against lower-level executives of major corporations, but hasn’t held the chief of a Fortune 500 company accountable in more than a decade.

While most observers believe Mueller will adhere to policy and not indict the president, will his report to Congress implicate the chief executive of the United States, if the evidence warrants it?

One man cannot fix the large problem on his own, however. “For these individual episodic financial crimes, the government can muster the capacity and courage to investigate and prosecute,” says Paul Pelletier, a former federal prosecutor who recently ran for Congress in a Democratic primary.

“The real question is whether, in the context of a national economic crisis, the Department of Justice has sufficient experience, resources and leadership to effectively tackle it. I’d argue that it’s pretty obvious it does not.”

For that, the Justice Department requires more resources and bodies than the government devotes to white-collar crime today, and probably some changes in the law.

Nevertheless, this should be a moment of reflection for white-collar prosecutors. It should not take a special counsel to uncover millions in bank fraud, money laundering and tax evasion. Using proper techniques, prioritizing crimes that can harm millions of people and stiffening their obsequious posture toward corporate executives will go a ways to remedying the situation.

Here’s the bad news, which will be the least surprising thing you’ll read today: the Trump administration is moving in the opposite direction.

Its law enforcement agencies are engaged in something of a regulatory strike, especially when it comes to white-collar enforcement.

Regulators are not policing companies or industries and are not referring cases to the Justice Department. The number of white-collar cases filed against individuals is lower than at any time in more than 20 years, according to research done by Syracuse University. The Justice Department’s fines against companies fell 90 percent during Trump’s first year in office, compared with in Obama’s last year in office, according to Public Citizen.

That must be sweet music to not just to other Manaforts and Cohens but also any corporate malefactors out there.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for their newsletter.