Organic

food worse for the climate

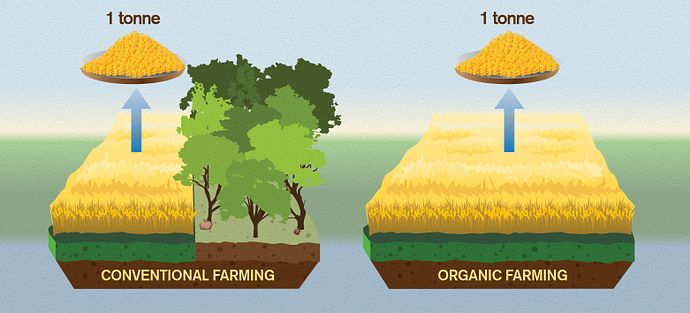

The crops per hectare

are significantly lower in organic farming, which, according to the study,

leads to much greater indirect carbon dioxide emissions from deforestation.

Credit: Yen Strandqvist/Chalmers University of Technology

The researchers

developed a new method for assessing the climate impact from land-use, and used

this, along with other methods, to compare organic and conventional food

production. The results show that organic food can result in much greater

emissions.

“Our study shows that

organic peas, farmed in Sweden, have around a 50 percent bigger climate impact

than conventionally farmed peas. For some foodstuffs, there is an even bigger

difference – for example, with organic Swedish winter wheat the difference is

closer to 70 percent,” says Stefan Wirsenius, an associate professor from

Chalmers, and one of those responsible for the study.

The reason why organic

food is so much worse for the climate is that the yields per hectare are much

lower, primarily because fertilisers are not used. To produce the same amount

of organic food, you therefore need a much bigger area of land.

The ground-breaking aspect of the new study is the conclusion that this difference in land usage results in organic food causing a much larger climate impact.

“The greater land-use

in organic farming leads indirectly to higher carbon dioxide emissions, thanks

to deforestation,” explains Stefan Wirsenius.

“The world’s food production is governed by international trade, so how we farm in Sweden influences deforestation in the tropics. If we use more land for the same amount of food, we contribute indirectly to bigger deforestation elsewhere in the world.”

“The world’s food production is governed by international trade, so how we farm in Sweden influences deforestation in the tropics. If we use more land for the same amount of food, we contribute indirectly to bigger deforestation elsewhere in the world.”

Even organic meat and

dairy products are – from a climate point of view – worse than their

conventionally produced equivalents, claims Stefan Wirsenius.

“Because organic meat

and milk production uses organic feeds, it also requires more land than

conventional production. This means that the findings on organic wheat and peas

in principle also apply to meat and milk products. We have not done any

specific calculations on meat and milk, however, and have no concrete examples

of this in the article,” he explains.

A new metric: Carbon

Opportunity Cost

The researchers used a new metric, which they call “Carbon Opportunity Cost”, to evaluate the effect of greater land-use contributing to higher carbon dioxide emissions from deforestation.

This metric takes into account the amount of carbon that is stored in forests, and thus released as carbon dioxide as an effect of deforestation. The study is among the first in the world to make use of this metric.

The researchers used a new metric, which they call “Carbon Opportunity Cost”, to evaluate the effect of greater land-use contributing to higher carbon dioxide emissions from deforestation.

This metric takes into account the amount of carbon that is stored in forests, and thus released as carbon dioxide as an effect of deforestation. The study is among the first in the world to make use of this metric.

“The fact that more

land use leads to greater climate impact has not often been taken into account

in earlier comparisons between organic and conventional food,” says Stefan

Wirsenius.

“This is a big oversight, because, as our study shows, this effect can be many times bigger than the greenhouse gas effects, which are normally included. It is also serious because today in Sweden, we have political goals to increase production of organic food. If those goals are implemented, the climate influence from Swedish food production will probably increase a lot.”

“This is a big oversight, because, as our study shows, this effect can be many times bigger than the greenhouse gas effects, which are normally included. It is also serious because today in Sweden, we have political goals to increase production of organic food. If those goals are implemented, the climate influence from Swedish food production will probably increase a lot.”

So why have earlier

studies not taken into account land-use and its relationship to carbon dioxide

emissions?

“There are surely many

reasons. An important explanation, I think, is simply an earlier lack of good,

easily applicable methods for measuring the effect. Our new method of

measurement allows us to make broad environmental comparisons, with relative

ease,” says Stefan Wirsenius.

The results of the

study are published in the article “Assessing the

efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change” in

the journal Nature.

The article is written by Timothy Searchinger, Princeton University, Stefan Wirsenius, Chalmers University of Technology, Tim Beringer, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, and Patrice Dumas, Cired.

The article is written by Timothy Searchinger, Princeton University, Stefan Wirsenius, Chalmers University of Technology, Tim Beringer, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, and Patrice Dumas, Cired.