Northwestern

researchers examine political divide behind climate change beliefs

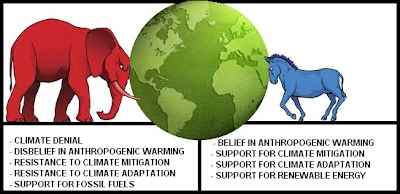

Despite a scientific consensus,

citizens are divided when it comes to climate change, often along political

lines, and scholars want to better understand why.

“We were interested in understanding the clear political divide in the U.S. on climate change beliefs and related policies and behaviors. Nearly all Democrats believe in human-induced climate change and many support climate mitigation policies, yet many Republicans remain skeptical,” said James Druckman, the Payson S. Wild Professor of political science in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern University and co-author of a recent article in Nature Climate Change.

Druckman, also associate

director of the University’s Institute for Policy Research (IPR),

said a prominent explanation for the divide is that it stems from

directional “motivated reasoning,”

meaning, in this case, individuals skeptical about climate change reject ostensibly credible scientific information because it contradicts what they already believe.

meaning, in this case, individuals skeptical about climate change reject ostensibly credible scientific information because it contradicts what they already believe.

“This is a depressing scenario for

those hoping to get movement on climate change opinions,” Druckman added.

“An equally consistent explanation

is that rather than flatly rejecting information that contradicts what

they already believe, people may simply differ in what they consider reliable

information,” said Mary McGrath,

co-author and assistant professor of political science at Northwestern.

In fact, much to their surprise, the authors found that there is virtually no evidence for the aforementioned “motivated reasoning.”

“We have little clear evidence that

can differentiate directional motivated reasoning from an accuracy motivated

model -- and the distinction between the two models matters critically for

effective communication,” said McGrath, a faculty fellow at IPR.

“Republicans might reject a

scientific report because they do not believe the authors of the report to be

credible or may be less trustworthy of science in general,” Druckman added.

“This is important because it means

closing the gap on climate change would involve offering distinct types of

evidence and messaging, and we imagine this actually may be what is happening

as we see more climate change messaging that appeals to values or religious

authorities. This also may be why in the last year or two, Republicans have in

fact significantly moved on climate change.”

A Stanford University study found

that Republicans underestimate the actual number of other Republicans that

believe in climate change and actually 57 percent believe there is climate

change.

Furthermore, according to a December New York Times article on Republicans’ views on global warming, majorities in both parties agree that the world is experiencing global warming and call for government action to address it, while they may disagree on the cause. In addition, both parties seem to find some common ground on remedies to combat climate change.

Druckman’s attention turned to the

challenge of climate change communications when he was asked to apply his

expertise to the issue by the Institute for Sustainability

and Energy at Northwestern (ISEN) in 2009.

Since that time, Druckman, who’s also affiliated with ISEN’s Ubben Program for Climate and Carbon Science, has been “building on a research agenda that looks at how different aspects of the message affect how particular groups of people move their opinions,” he said.

Since that time, Druckman, who’s also affiliated with ISEN’s Ubben Program for Climate and Carbon Science, has been “building on a research agenda that looks at how different aspects of the message affect how particular groups of people move their opinions,” he said.

McGrath is also continuing this work

with a further methodological review of experiments on climate change opinion

formation.

“The evidence for motivated

reasoning in climate change preference formation” published online earlier this

week in Nature Climate Change.