URI history

professors to examine ‘fake news’ through a historical lens

On Monday, April 1, four University

of Rhode Island history professors will present the discussion “Fake News: A

Historical Perspective” from 4 to 6 p.m. in the Agnes G. Doody Auditorium in

Swan Hall, 60 Upper College Road, on the Kingston campus.

The event is free and open to the public.

The event is free and open to the public.

While the term “fake news” has come

into wide use since the 2016 presidential election, the forum will show that

fake news – whether as a means to further a political agenda or cast doubt on

the legitimacy of a news report – may be as old as news itself.

“This is a very timely topic,” says

Joelle Rollo-Koster, professor of medieval history and organizer of the forum.

“This event will show people a range of fake news throughout history. It’s

nothing new. It’s something that has always existed.”

The forum also highlights the value

of history in combatting fake news, says Catherine DeCesare, a senior lecturer

in U.S. and Rhode Island history.

“The study of history is extremely

important and certainly relevant in today’s society,” says DeCesare. “Knowledge

about the past can be used to inform contemporary society.”

During the event, each professor will look at fake news as it relates to their area of study. Rollo-Koster will discuss the use of propaganda in justifying the first Crusades in the 11th century and, a millennium later, the war on terror, while DeCesare will focus on the intersection of fake news and Rhode Island history.

Rod Mather, history department chair

and professor, will address fake news and shipwrecks, and James Mace Ward, a

senior lecturer who specializes in modern European history, will discuss the

polarizing legacy of Jozef Tiso, a Slovakian president and priest who was

hanged for war crimes after World War II.

In times of political or economic

crisis or war, says DeCesare, there is an underlying fear within the community

that often results in increased negative propaganda as a political faction

tries to hold on to or consolidate power.

In the early 1840s, for example, the

Law and Order Party was formed in Rhode Island to battle the expansion of

voting rights and citizenship to immigrants, she says. At the time, large

numbers of Irish immigrants were settling in the state.

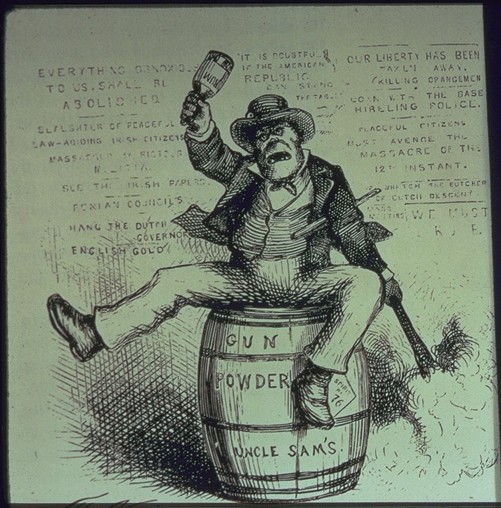

The Law and Order Party used

political posters – or broadsides – written in the form of sermons to attack

immigration, claiming it would place government, civic and political

institutions, schools and religious freedom “under the control of the POPE of

ROME through the medium of thousands of NATURALIZED FOREIGN CATHOLICS.”

“Broadsides, newspapers, speeches

and sermons were used in the past to control a message,” she says.

“Today, cable news, network news and especially social media are used to promote fake news. The method and technology have changed, but not the fundamental reason for propaganda.”

“Today, cable news, network news and especially social media are used to promote fake news. The method and technology have changed, but not the fundamental reason for propaganda.”

In 1095, Pope Urban II’s tool was

the sermon in calling on European Christians to take up arms in a righteous war

against Muslims, says Rollo-Koster.

In 1095, Pope Urban II’s tool was

the sermon in calling on European Christians to take up arms in a righteous war

against Muslims, says Rollo-Koster.

In the late 11th century,

Byzantine Emperor Alexius I sought help from Urban II when Seljuk Turks were

threatening the Byzantine Empire. The Turks, Sunni Muslims, had taken control

of parts of the Holy Land, now the Middle East.

In a volatile sermon, Urban called

for Christians to reclaim the Holy Land, saying it was God’s will and claiming

that Muslims were committing atrocities.

Rollo-Koster compares Urban II’s

rhetoric with President George W. Bush’s claims of weapons of mass destruction

to justify the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

“Urban II uses all of this

exaggerated rhetoric,” she says. “Then you have Bush calling the war on

terrorism a crusade. The rhetoric is the same. Bush says there are weapons of

mass destruction. The weapon of mass destruction for Urban II in 1095 is the

claim that Muslims are killing, roasting and eating babies.

“It’s all this idea of moving people

for political reasons with fake arguments. After all what is fake news? It’s

manipulating opinion in a war of propaganda.”

The story of Jozef Tiso, leader of

the Nazi satellite state of Slovakia during World War II, highlights the use of

fake news by competing political ideologies, says Ward.

“Tiso has been the subject of polar

interpretations since he entered politics in 1918,” says Ward, author of

“Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Jozef Tiso and the Making of Fascist

Slovakia.”

“The fact that he was a head of state and a priest who helped to deport some 60,000 Jews to their deaths during the Second World War strengthened the desire to understand him in black and white terms.”

“The fact that he was a head of state and a priest who helped to deport some 60,000 Jews to their deaths during the Second World War strengthened the desire to understand him in black and white terms.”

After Tiso’s execution in 1947, he

was falsely accused of treason against Czechoslovakia dating to its creation,

and also falsely promoted as saving thousands of Jews. “Both are good instances

of an earlier version of fake news,” Ward says, “the propaganda of the state

versus that of its opponents.”