The uphill battle for communities that ban pesticides

Meg Wilcox for the Environmental Health News

On a

recent moonlit evening, with spring peepers in chorus, a dozen Wellfleet

residents gathered inside their town's grey-shingled library for a public

information session on the controversial herbicide, glyphosate.

On a

recent moonlit evening, with spring peepers in chorus, a dozen Wellfleet

residents gathered inside their town's grey-shingled library for a public

information session on the controversial herbicide, glyphosate.

A bucolic, seaside town

with less than 3,000 year-round residents, Wellfleet is famed for its

picturesque harbor and sweet, briny oysters.

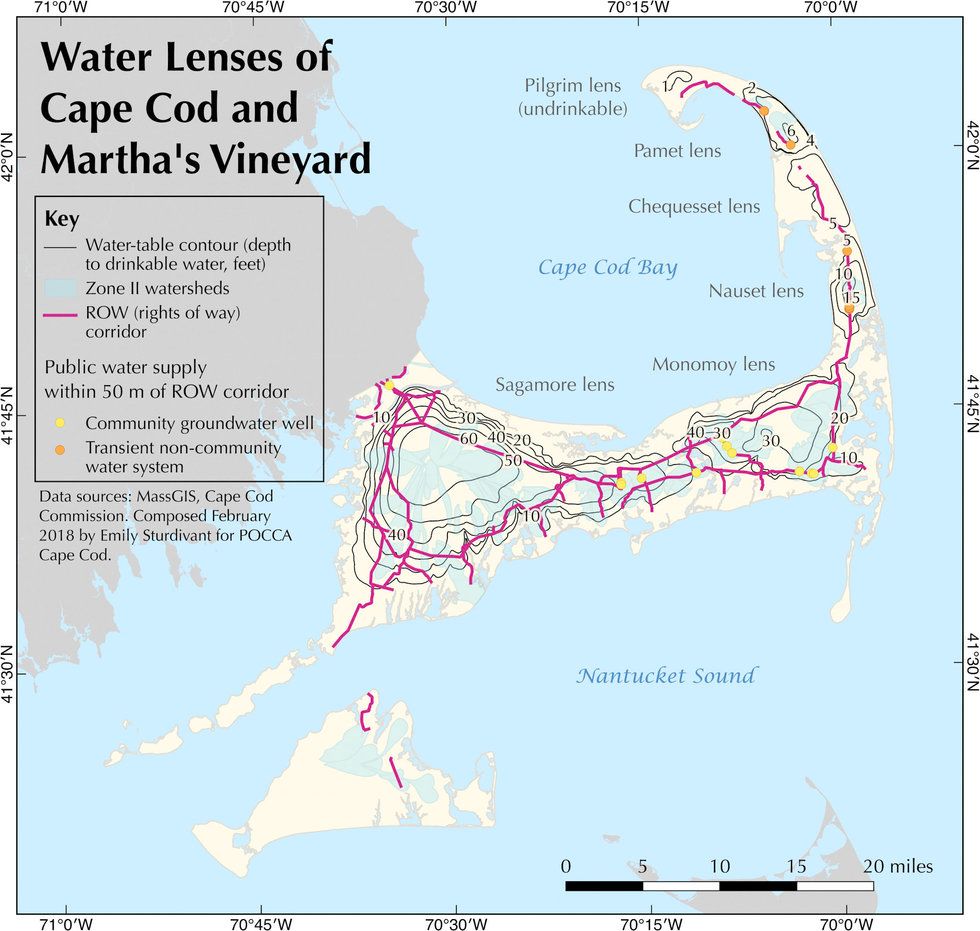

Its residents, like the

rest of Cape Cod, rely on a sole source of drinking water, a shallow

underground aquifer, and protecting that aquifer from pollutants such as

pesticides and septic wastes from household wastewater is a huge concern.

Semi-rural, with 1,000

ponds, extensive wetlands and pristine beaches, Cape Cod is like a giant sandbar.

Anything spilled on its sandy soils can seep quickly into the groundwater and

pollute its well water and interconnected system of surface waters.

And so, as organic

landscaper and founder of the advocacy organization Protect Our Cape Cod

Aquifer (POCCA), Laura Kelley spoke about the dangers

of glyphosate, she told Wellfleet residents, "[state pesticide]

regulations don't match our ecology."

She was referring to the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources' (MDAR) allowed use of glyphosate to control weeds on rights of way under power lines on Cape Cod. Kelley, and other residents, are concerned that the weedkiller isn't as safe as regulators say it is, with emerging science suggesting harmful impacts from cancer to birth defects to disruption of hormones and other biological functions that can linger for generations.

Studies showing

glyphosate can persist in groundwater worry them, as do recent

high-profile jury awards for

people claiming their cancer was caused by the herbicide.

Herbicide use by the

region's electricity provider, Eversource, is therefore wildly unpopular on the

Cape. All 15 towns are locked in battle with both Eversource and MDAR, the

authorizing agency, over the issue.

Cape Cod isn't alone in

facing an uphill battle at carrying out local pesticide policies. While more

than 140 communities across

the U.S. have now passed a pesticide ordinance or law, and the movement has

been scoring big wins—from L.A. County's glyphosate moratorium,

to Portland, Maine's synthetic

pesticide ban, to Montgomery County, Maryland's

appellate court victory upholding its Healthy Lawns Act

to new legislation that would ban

glyphosate from New York City parks—moving from victory to

implementation of laws or ordinances can be a mixed bag.

Some localities find

that passing a law is but a battlefield victory in a prolonged war. State-level

preemption laws, resistance from implementing agencies, and lax EPA rules can

lead to policies that simply sit on a shelf or are challenged in court.

Advocates say that a

proactive organic management approach may be the best way to prevail in the

long run. A systems approach focusing on soil health is not only more effective

for turf management, but its positive message resonates with the public.

"The holistic

response motivates parents because it's their kids, and they're worried about

water contamination and drifting of pesticides," Jay Feldman, executive

director of Beyond Pesticides, told EHN. "Then they learn they can play a

part in reducing fossil fuel use and sequestering carbon [through organic

management], not to mention the insect apocalypse."

State preemption

Like most states in the

nation, Massachusetts' state law preempts localities from setting their own

pesticide policies on private property. While the land under power lines is

owned by the towns, the National Seashore or

private residences, Eversource is granted an easement which permits it to

maintain it.

Five Cape Cod towns have

banned glyphosate use on town property, but they are unable to stop

Eversource's spraying on rights of way within their boundaries.

Preemption laws prohibit

localities from adopting pesticide ordinances that are stricter than state

regulations, which tend to closely follow the EPA. Forty-three states passed

these laws, for private property, largely in response to chemical industry

pressure in the 1990s, Drew Toher, community resource and policy director at

Beyond Pesticides, told EHN.

As communities have grown concerned that the federal government isn't protecting their health, they've therefore been passing pesticide ordinances where they have authority, on public property.

As communities have grown concerned that the federal government isn't protecting their health, they've therefore been passing pesticide ordinances where they have authority, on public property.

But even those ordinances

can face resistance from opponents seeking a broad interpretation of preemption

laws, Toher said. In Maryland, which doesn't have a preemption, opponents of

Montgomery County's Healthy Lawns Act filed suit against the law, claiming

preemption was implied. Opponents lost, in a major victory for the county.

Preemption is the key

obstacle for Cape Cod but EPA's lax rules are also at play because they allow

state officials to dismiss community concerns. EPA claims that glyphosate has

no public health risk, but the International Agency for Research on Cancer

(IARC) concluded in 2015

that glyphosate is a probable carcinogen, and an international group of scientists later concurred with that finding.

The scientist group says that EPA is relying in part on data provided by industry researchers that has not been peer-reviewed.

The scientist group says that EPA is relying in part on data provided by industry researchers that has not been peer-reviewed.

MDAR has determined that

glyphosate is safe for sensitive environments, based on a review that refers

to EPA data but does not mention IARC's finding.

Eversource supervisor

for transmission management, Bill Hayes, therefore uses glyphosate, he told

EHN, because it's on MDAR's approved list.

Hayes argues that using

herbicides is "best management practices" on rights of way and that

herbicide use actually protects habitats better than mechanical means, like

mowing, which can indiscriminately destroy vegetation and lead to soil erosion.

Public health scientists

don't buy that argument. "Explore alternatives before spraying something

that's likely to cause cancer around the Cape Cod environment," Richard

Clapp, professor emeritus of environmental health, Boston University School of

Public Health, told EHN. "There are other ways to control poison

ivy."

For some communities,

repealing state preemption laws may be what's needed to give them the authority

to regulate pesticides in a way that works for their local environment. Cape

Cod's state representative Dylan Fernandes, has filed legislation that would end the state's

pesticide preemption. The bill is picking up support, with 50 to 55 sponsors,

Fernandes told EHN.

"Even a casual

observer has heard just how much the EPA has rolled back and even tried to hide

science," Fernandes told EHN. "I fundamentally believe that local residents

should have a say on what pesticides are being sprayed on the land in which

they live."

Bills to repeal

preemption have been filed in other states, including Minnesota, Connecticut

and Illinois, but none have yet succeeded. Still, Toher is buoyed that the

movement was able to beat back an attempt to slip federal preemption of

local pesticide laws into the farm bill last year.

"That fight

galvanized local legislators," he said. "I see a lot of wind at our

backs."

Montgomery County,

Maryland: Resisting agencies

Even in states without

preemption, communities can face resistance from agencies charged with

implementing local pesticide laws.

Montgomery

County—Maryland's largest county, with more than a million residents—passed in

2015 the Healthy Lawns Act, the

first U.S. county law to restrict pesticides for cosmetic use on both private

and public property.

A lawsuit was immediately filed against the private property portion of the law, but just last month Maryland's Appellate Court upheld the law, and—to advocates delight—cited Rachel Carson in the ruling's opening.

A lawsuit was immediately filed against the private property portion of the law, but just last month Maryland's Appellate Court upheld the law, and—to advocates delight—cited Rachel Carson in the ruling's opening.

Though the public

portion of the law wasn't challenged in court, the Montgomery Parks Department

has resisted implementing the law as advocates intended, Julie Taddeo, founder

of Safe Grow Montgomery, told EHN.

The law left wiggle room

for the parks department to make "certain parks" pesticide free, and

in four years, the department has done so for only 10 out of 426 parks, and

currently doesn't have plans to go beyond that, according to an email from

Montgomery Parks Deputy Director John Nissel.

The parks department is

also dragging its feet at a requirement to run a pilot pesticide-free program

on five playing fields by 2020, and its website indicates that it continues to

use herbicides for routine weed control, when pesticides should be the last

resort in an integrated pest management (IPM) approach, Taddeo said, referring

to a practice that aims to minimize risks to human health and the environment

by following a hierarchy of pest management options that moves from less

harmful (i.e., mechanical removal) to more harmful (i.e., pesticides).

County Councilor Tom Hucker

concurs with Taddeo. "They [parks department] don't seem the least bit

concerned about the public health exposure." But he thinks it will get

increasingly untenable for the parks department to continue using pesticides,

with the recent court ruling.

Nissel defended the

department's actions in an email, saying that it had met steps and dates for

implementation of the law, including designating some parks pesticide-free, and

implementing maintenance of playing fields using IPM.

Resistance from

implementing agencies is common, Chip Osborne, founder of Osborne

Organics, and a national expert on organic turf management, told

EHN. "They've been told by the pesticide industry to expect failure [with

organic management]," and some go to great lengths to defend pesticide

use. Osborne himself was a pesticide applicator for 25 years. Then in 1997, he

says he had an "aha moment" that "it's not really what it's

cracked up to be."

Long-time Massachusetts'

public health activist Ellie Goldberg agrees. "In Newton the parks

department said kids could trip on weeds and hurt their knees on the rocks if

they didn't use herbicides. They quoted pesticide manufacturer's claims that

the pesticides were safe to justify using poisons on playgrounds and playing

fields."

Even on Cape Cod, the

Falmouth Conservation Commission is resisting following

the town Board of Health's moratorium on glyphosate.

Proactive organic

management

Montgomery County's

unhurried approach to implementing the Healthy Lawns Act points to what

advocates says can be a problem with IPM. It allows pesticide use as a

"last resort," which is open to interpretation.

A proactive organic

management approach, they say, may be better for long-term success.

Banning a single

pesticide, like glyphosate, can be a smart strategy for galvanizing support,

particularly with recent high-profile jury awards.

But that strategy can fall short in the long run because a systems approach is

what's needed to fully move from conventional to organic management.

"Whether you're

managing a backyard, or national park, or a soccer field, you have to embrace

it as managing a system and the most important thing is soil health, the

biological life of the soil," Osborne told EHN. Osborne chairs Marblehead,

Massachusetts' Recreation and Parks Commission, which has practiced organic

management for nearly 20 years.

Shifting from a mindset

of feeding grass to feeding the soil builds the soil's microbial diversity, and

that helps the system withstand weed and pest pressures, Toher said. Plus, it

has "multiple beneficial bottom lines for human health, water quality and

pollinator populations."

Most important, says

Osborne, is to not just swap out a synthetic pesticide for an organic pesticide

like acetic acid. That doesn't lead to the systems change that's needed, and

organic pesticides aren't problem-free.

And, said Toher,

advocating for proactive organic management can help the environmental

community move beyond the "whack-a-mole approach" of fighting one

pesticide after another.

Communities in Maine,

such as South Portland and

Ogunquit have been adopting this approach because the state has "an

affirmative stance on the right of localities," said Toher.

Accountability and

education

Some communities, like

Marin County, California, which no longer uses synthetic pesticides on any of

its parks and playing fields, have found a formula for success that includes

public engagement, accountability and education.

Nearly 20 years ago,

Marin County, created an IPM Commission, to oversee the park

department's pesticide ordinance. The commission holds quarterly meetings, open

to the public, and produces public reports with a full accounting of its

activities.

Parks Department

director Jim Chakya told EHN the commission creates "a forum for the

community to come in and provide feedback. It's a really good place for some of

the challenging conversations around issues like glyphosate."

Sierra Club activist

Barbara Bogard agrees that the commission has been instrumental at fostering

trust with the community, but told EHN the turning point in Marin was the

election of Larry Bragman, who ran on a "no herbicides in the watershed

platform," to the water district board in 2014. That "put Marin

County elected officials on notice that this issue could turn an

election."

Marin has also put

$140,00 towards a public education campaign, and taken other steps, including a

quarter-cent sales taxes that's helped to fund the department's IPM efforts.

"This is our

water"

Back on Cape Cod, boards

of selectmen from all 15 towns have passed resolutions calling for zero

herbicide use by Eversource, and formally appealed to MDAR,

as have the region's state representatives and the Cape Cod Commission, a

regional planning agency.

Back on Cape Cod, boards

of selectmen from all 15 towns have passed resolutions calling for zero

herbicide use by Eversource, and formally appealed to MDAR,

as have the region's state representatives and the Cape Cod Commission, a

regional planning agency.

The town of

Brewster—which has vernal pools, ponds, lush bird habitat and well fields in

its rights of way— has secured a preliminary injunction in Barnstable Superior

Court against Eversource.

MDAR is expected to

announce this summer whether it approves Eversource's latest plan to

spray glyphosate, as well as the pesticides imazapyr, metsulfuron methyl and

triclopyr, in rights of way in 13 Cape Cod towns (excluding Brewster due to the

court case).

MDAR declined a request for interview, but based on past decisions, it's unlikely the agency will disallow the herbicide use.

MDAR declined a request for interview, but based on past decisions, it's unlikely the agency will disallow the herbicide use.

Kelley, of Protect Our

Cape Cod Aquifer (POCCA), has been laboring, with the Association

to Preserve Cape Cod, to persuade town boards of health and

selectmen to strengthen their pesticide restriction policies.

An eleventh generation

Cape Cod resident, who grew up on a Quaker sheep farm, she's organized town

brigades to hand clear vegetation on rights of way to demonstrate that

alternative methods can work.

"This is our water.

It's up to us to protect it," she told EHN.