By BEV BETKOWSKI

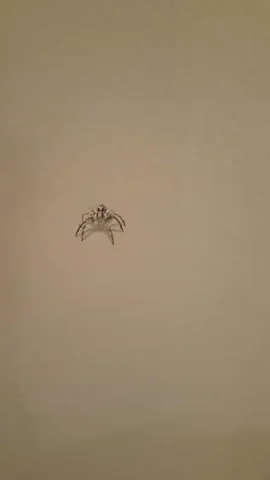

When that itsy-bitsy spider climbs

up the spout, resist the urge to stomp it out—even if it makes your skin crawl.

When that itsy-bitsy spider climbs

up the spout, resist the urge to stomp it out—even if it makes your skin crawl.

The leggy bugs get an unfair

reputation as being poisonous and creepy, when in fact most of them,

particularly those native to North America, are harmless to humans and good for

the ecosystem, said a University of Alberta expert.

“They aren’t bad at all, there’s

just this innate fear we have of spiders,” said conservation biologist Jaime

Pinzon, who studies the arachnids as a U of A adjunct

professor and researcher with the Canadian Forest Service. “If you

don’t bother them, they won’t bug you.”

Pinzon, who says he’s been bitten

“hundreds of times” with no harm done by spiders in the course of his work,

notes that only a handful of the 48,000 species known worldwide—including more

than 600 species of spiders in Alberta alone and about 1,500 species in

Canada—are venomous to humans, most of them living in tropical climates.

And though some might fear climate

change could bring potent tropical spiders to North America, there’s no strong

evidence to suggest it, Pinzon noted.

“It’s too premature to say that, because there are gaps in understanding the distribution ranges of many species. There may be some species that could move northward as the climate changes, but winter is a filtering process and it is unlikely they can establish populations in northern areas. There is still much to know about whether a species’ distribution range has expanded because of climate change or because it’s just undiscovered.”

Based on his research on

Canadian prairie spiders and their responses to forest harvesting, a number of

species previously not known to be in Alberta have been discovered in the

province over the last 10 to 15 years, but that’s not unusual, Pinzon said.

“The research has been done in areas

that hadn’t been studied in the past, so it isn’t surprising to find unreported

species there. The more research we do and the more we catalogue species in

different parts of the province, the better we will understand their

distribution and the overall spider biodiversity in Alberta.”

Tropical spiders do occasionally

make it to Canada by way of shipping containers, but they can’t withstand

Canada’s cold winters, he added.

“The chances of being badly affected

by a spider bite are extremely low,” he said, adding that unless you actually

see a spider bite you, that tiny wound is more likely from a mosquito or

another type of bug bite that becomes infected.

“Spiders don’t normally bite you

just because you are around them. They are very shy and they tend to escape,

not to confront.” And only the largest ones, with bodies the size of dimes or

larger, can penetrate human skin, he added. “You’d just feel a pinch, but small

spiders just cannot puncture the skin.”

While most spiders carry venom, it’s

reserved for catching food prey, not aimed at humans, and is in such tiny doses

that it poses little harm, though people with weakened immune systems, the

young or the elderly could have a stronger reaction.

“Of course, there are species of

medical concern, such as brown recluses, which are an issue in the United

States; however, there are no confirmed reports of brown recluses occurring in

Canada,” Pinzon added.

If bitten, wash the bite and see a

doctor if it becomes tender or swollen, Pinzon suggested.

“If a bite gets infected, it’s not

likely because of the venom, but because of the bacteria the spider carries in

its mouth.”

Scary but helpful

The squeamishness some people feel

for the scurrying critters is due at least in part to the human evolution of

our perception of spiders, Pinzon believes.

“Our ancestors evolved in the

presence of spiders and most likely some of them were poisonous, so there would

have been a natural aversion to spiders, the same as to snakes or any other

venomous creature. People would have feared anything that was poisonous. That

has carried through our history—spiders are seen as bad guys, particularly in

books and movies, and that makes things even worse. And we tend to teach our

kids to be afraid of the things we’re afraid of.”

But the creepy-crawlies are helpful

to humans, Pinzon said.

“They eat a wide variety of

creatures, including flying insects like flies, mosquitoes and other bugs that

can bite you. Spiders are natural controllers of insect populations, some of

which are pests in gardens and crops. Without spiders, you’d see many more of

these bugs.”

In turn, they also serve as food for

birds, other insects and spiders, showy dragonflies and amphibians like frogs

and salamanders.

“They’re an important part of their

diet,” Pinzon explained.

They’re everywhere

We have to coexist with spiders

anyway, Pinzon added. They live everywhere except at the perpetually icy North

and South poles or in the ocean. They can withstand the coldest winter,

surviving as babies or sometimes as eggs under winter snowpack or loose bark.

There are species that overwinter as adults and are active during the whole

winter.

“We have found active spiders under

the snow even in January and February,” Pinzon said. “Native species are well

adapted and develop antifreeze in their bodies. On a warm winter day, you may

even be able to see an odd spider here or there walking on the snow.”

They’ll also be living indoors, he

added.

“To keep them out of your house is

almost impossible. Cool, dark areas like basements harbor them year-round,

even if you don‘t see them.They can crawl in through any open window, door or

small crack; they will find their way in if there’s something to eat.”

But even so, people don’t need to

worry about their homes being infested with nightmare colonies of spidey

families.

“To establish a population that

carries on year after year, you need very right conditions—enough prey and

hiding places—so even though basements are cool and damp and dark, they don’t

have those conditions.”

If you do find one inside, don’t

stomp it into lifeless mush, Pinzon said. Instead, use a piece of paper to shoo

the spider into a cup and then release it outside near a tree, bush or other

vegetation.

If possible, leave spider webs

alone, he added.

Though not all spiders build webs,

the silky structures are vital to those that do.

“The silk is the main tool spiders

have for a variety of activities, such as wrapping their prey, keeping their

eggs safe and, of course, building their webs. The silk spiders use is costly

material, because they invest a lot of energy in producing it. Since

web-weaving spiders don’t move around a lot, building a web is an expenditure.

Many species even eat their old webs to recycle the silk.”