The recent shooting attack in which a young white man is accused of killing 22 people in a Walmart in El Paso fits a new trend among perpetrators of far-right violence: They want the world to know why they did it.

The recent shooting attack in which a young white man is accused of killing 22 people in a Walmart in El Paso fits a new trend among perpetrators of far-right violence: They want the world to know why they did it. So they provide a comprehensive ideological manifesto that aims to explain the reasoning behind their actions as well as to encourage others to follow in their steps.

In the past, only leaders of far-right groups did this. Now, it’s common among lone-wolf perpetrators, such as the alleged perpetrator in El Paso.

In the past decade, the language of white supremacists has transformed in important ways. It crossed national borders, broadened its focus and has been influenced by current mainstream political discourse.

I study political violence and extremism. In my recent research, I have identified these changes and believe that they can provide important insights into the current landscape of the American and European violent far-right.

The changes also allow us to understand how the violent far-right mobilizes support, shapes political perceptions and eventually advances their objectives.

New identity crosses borders

Since the early stages of the American white supremacy movement in the mid-19th century, the movement has always emphasized the superiority of Western culture and the need for segregation between racial groups in order to maintain the purity and dominance of the white race.For example, in the 1980s, a Ku Klux Klan affiliate published a map allocating specific parts of the U.S. to specific ethnic communities. The map makers imagined Jews limited to the New York area, while Hispanics were to live in Florida.

But recently, a growing number of far-right activists have preferred to focus on cultural and social differences between communities, rather than on attributes such as race and ethnic origin.

They justify their violence as a way to preserve certain cultural-religious practices, rather than relying on their old justification – maintaining the genetic purity of the white race. In these activists’ view, the battle has moved from genes to culture.

For example, a member of the National Socialist Movement, an American neo-Nazi organization, wrote in a 2018 online post that white American is an identity like African American or Jewish American.

In a statement that probably wouldn’t have been made by previous generations of neo-Nazis, the member wrote that all whites should come together, using their knowledge and weapons, to stop non-Europeans from pushing their secular agenda via government and media power.

Countering liberal left’s cultural influence

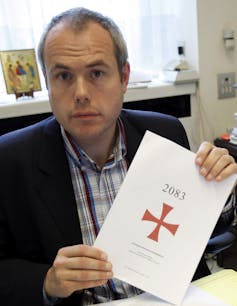

Another traditional theme of the far-right discourse – preserving the patriarchal order from attacks from the left – has grown in prominence.Andres Breivik, who killed 77 people and injured more than 300 in July 2011 in Europe’s most lethal act of white supremacism, issued a manifesto shortly before his rampage.

In it, he stated that the politically correct terminology which is becoming more prevalent in the West intends to “deny the intrinsic worth of native Christian European heterosexual males” who were reduced to an “emasculate[d] … touchy-feely subspecies.”

Such sentiments are becoming more prevalent in the white supremacist forums, and reflect another component of what they perceived as an ongoing cultural war to preserve the white Christian way of life.

New transnational culture

The declining emphasis by the far-right on nationalism has led to the adoption of a transnational identity based on race, culture and religion.Simply put, they feel closer to whites in other countries than non-whites who live in their neighborhood.

This explains why we have seen a global spread of violent white nationalism in recent years as the far-right finds kinship with like-minded nationalists in other countries.

Racial identity was always a prime component in the identity of far-right activists, but it was usually framed by local politics. In the past, racist British skinheads focused mainly on what they perceived as the interests of the British white working class. Today the rhetoric of most skinheads focuses on international geopolitics, although local issues haven’t been abandoned.

The attack in Christchurch, New Zealand, in which an Australian white supremacist killed 51 Muslim worshippers in a mosque on March 15, 2019, reflects that far-right activists seem to increasingly embrace a regional, if not global, perspective in the way they define their constituencies and the threats they are facing.

The Christchurch attacker’s manifesto was clearly inspired by far-right rhetoric from European and American groups, such as notions of “white genocide.” He specifically mentions Norway’s Breivik as a role model.

Legitimizing far-right ideology in the US

In the U.S., what’s different about the current rhetoric of the far-right is that they are now using terminology that can also be found in some mainstream political parties and movements, aiding their efforts to gain popular legitimacy.For example, the United Northern and Southern Knights of the Ku Klux Klan released a new set of organizational goals a couple of years ago.

Beyond their longstanding, bedrock belief – the protection of the white race – they also declare support for restricting immigration and free trade and ending or limiting foreign aid. They want government to provide protection to small businesses, agricultural workers and gun owners.

This broad ideological shift also spilled over to some far-right skinhead organizations. Volksfront, for example, declares in its online mission statement that beyond white nationalism, the organization will fight for economic issues, states’ rights, crime repression and labor rights.

Donald Trump’s language about the need to restore order to the streets of America, as expressed in his inaugural address, is also evident in the language of American white supremacists. In a poster produced by the skinhead group Keystone United, they call for harsher punishments for drug dealers.

Donald Trump’s language about the need to restore order to the streets of America, as expressed in his inaugural address, is also evident in the language of American white supremacists. In a poster produced by the skinhead group Keystone United, they call for harsher punishments for drug dealers. The demand for stricter punishment of criminals is echoed in many racist group platforms.

These include support of death penalty expansion, an important point of discussion mainly in skinhead message boards, and levying harsher punishments for sexual offenses.

Since minorities are overrepresented among American incarcerated population, far-right activists see these criminal justice policies as a more “legitimate” way to “punish” members of minority groups.

Two future trends

These changes in the discourse of the far-right suggest two important trends.The first is the growth in the international nature of far-right violence, posing a challenge to law enforcement across borders.

Second, the growing overlap between the language of the far-right and the rhetoric of elected officials illustrates how the current polarization in the political system, and delegitimization of minorities by political leaders, can provide legitimacy for radical practices and violence and broader acceptance of ideas, concepts and statements that in the past were the domain of the far-right.

I fear these dynamics are likely to encourage additional far-right activists to express their views via violence. The emerging evidence that the El Paso shooter was inspired by popular theories in the far-right rhetorical universe, such as that of the “great replacement,” is a clear warning sign.

Arie Perliger, Director of Security Studies and Professor, University of Massachusetts Lowell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.