A

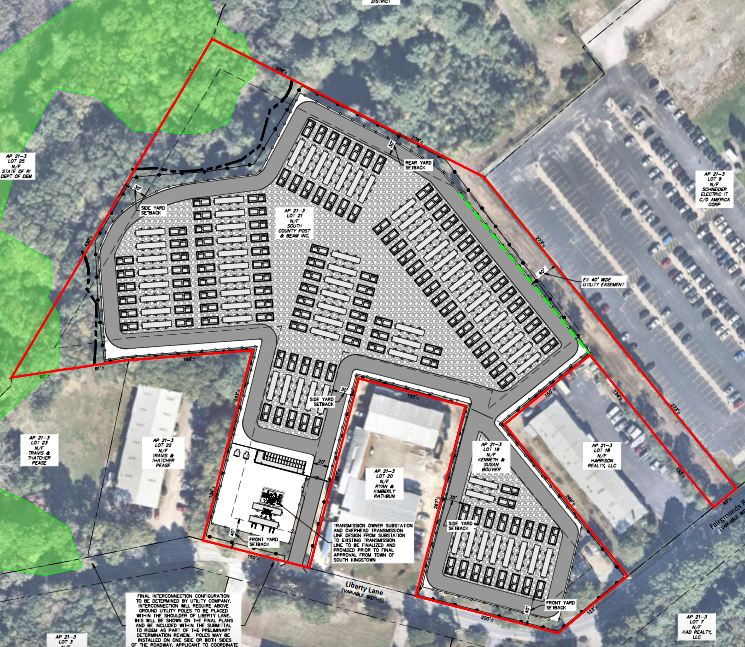

180-megawatt battery-storage facility has been proposed for the village of West

Kingston, R.I. (Plus Power)

By

TIM FAULKNER/ecoRI News staff

WEST

KINGSTON, R.I. — Before Rhode Island’s first utility-scale battery-storage

facility can be built, it must be decided whether the state or town has

ultimate say over the project.

At

the local level, the town of South Kingstown must figure out if the Narragansett Energy Storage

Project can be built on a 7.4-acre site that sits within a

drinking-water supply area, known as a protected groundwater overlay

district.

Forthcoming

reviews by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) and

its Division of Agriculture will determine if chemicals used at the lithium-ion

battery facility pose a risk to the water supply.

Once

the opinions are received, the town will begin its review, including a public

hearing, for the project proposed on a mostly wooded site near the Kingston

train station.

The

town’s evaluation, however, may be limited if the state Energy Facility Siting

Board (EFSB) decides that the 180-megawatt project is a major energy producer.

The EFSB must approve any power plant that generates 40 megawatts or more of electricity. The question is whether the facility technically generates electricity.

The EFSB must approve any power plant that generates 40 megawatts or more of electricity. The question is whether the facility technically generates electricity.

The

developer, Plus Power, based in New York and San

Francisco, has claimed that the project isn’t a power plant, and therefore

doesn’t require EFSB review.

The

proposed facility will not generate electricity, as it will “merely store and

release electricity,” according to a document Plus Power

filed with the EFSB.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Regardless of the environmental merits of this project, this is yet another example of clearing out a large area of woods for a commercial energy project. I think the community would be much more receptive to this project if it used an old quarry, sandpit, brownfield site or closed landfill. I think the developers are aware that public opposition, a la Invenergy in Burrillville, can kill a project and will certainly jack up the costs. Location, location, location. - Will Collette

The EFSB review process is typically longer and more comprehensive than the local permitting process.

The EFSB review process is typically longer and more comprehensive than the local permitting process.

Despite

the delays for this project, battery storage is considered essential to

widespread deployment of renewable energy. Rhode Island and other states hope

to achieve climate-emission reduction goals by replacing fossil-fuel power with

thousands of megawatts of wind and solar energy.

Solar

and wind power, however, are limited by intermittency, the term that describes

gaps in electricity output when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t

blowing.

Battery-storage

facilities fill those gaps by taking electricity from the grid when demand is

low and power is more plentiful. They return electricity to the system when

renewables have reduced output or during power spikes such as heat waves and

cold snaps.

Stored

power also reduces the reliance on polluting “peaker” power plants that

typically run on coal or oil and only operate during high-demand periods.

“Energy

storage technology is an important tool in the long-term health of a modern

power system,” the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resource (OER) wrote in a July 15 letter of support for excluding the

EFSB from the permitting process.

The

proposed Narragansett Energy Storage Project is made up of a series of 40-foot

shipping containers that hold inverters, transformers, and batteries that store

between 3.5 and 4.5 megawatts.

Plus

Power says the facility isn’t a power producer and loses between 5 percent and

15 percent of its energy between storage and discharge.

The

company noted that EFSB regulations don’t name energy storage as a power

generator and, despite having the opportunity to do so, the General Assembly

hasn’t classified energy storage as a power plant. Therefore, the facility

isn’t subject to the same scrutiny as a coal, natural-gas, or nuclear power

plant, according to Plus Power.

The

company said oversight and permitting for the project should be conducted by

the local zoning board, state entities such as DEM and the Coastal Resources

Management Council, and perhaps the Army Corps of Engineers. The

interconnection part of the project, however, will be reviewed by the EFSB and

ISO New England to assure that it complies with the regional electric grid.

The

Rhode Island Division of Public Utilities and Carriers (DPUC) has agreed that

the EFSB has no authority to adjudicate energy storage facilities.

In a letter to the EFSB, the DPUC says the lack

of explicit reference of energy storage in state law or by the General Assembly

means oversight of such facilities can’t be implied in the siting board’s rules.

OER

said municipalities should be allowed to decide aesthetics and setbacks from

property lines.

“Municipalities

are best suited to ensure siting and zoning ordinances for energy storage

facilities are consistent with local priorities and aligned with municipal

values,” Nick Ucci, OER’s deputy commissioner, wrote in the agency’s letter to

the EFSB.

National

Grid, which is allowed to own and operate energy-storage facilities in Rhode

Island, says it also doesn’t want the EFSB to be

the permitting entity. The state’s primary electric and gas utility agrees that

battery systems only store and release electricity.

National Grid also notes

that Massachusetts makes a distinction between energy storage and power

generation and regulates them independently.

Massachusetts,

however, has yet to rule on whether a storage facility should be approved by

the state’s energy siting board.

The

Massachusetts Energy Facilities Siting Board is currently deciding if it has jurisdiction

over the proposed 150-megawatt Cranberry Point Energy Storage Facility in

Carver, Mass. The Mass. EFSB reviews power plants that generate 150-megawatts

or more. A decision on the lithium battery storage facility is expected in the

coming months.

New

York also doesn’t declare whether energy storage is a major power producer, but

it does offer guidelines for building a facility.

Regardless

of its decision, the EFSB will review the interconnection of a substation

used by the proposed energy-storage facility. If the EFSB determines that the

project is a major energy producer, then all siting and permitting will be

decided by the three-person board.

If

built, the Narragansett Energy Storage Project would have an expected life of

20 years. But the operation would continue with the installation of new

equipment, according to Plus Power.