By FRANK CARINI/ecoRI News

Five General Assembly

sessions have come and gone since lawmakers passed the Resilient Rhode Island

Act of 2014.

Five General Assembly

sessions have come and gone since lawmakers passed the Resilient Rhode Island

Act of 2014. It’s still lauded as a significant piece of legislation, and it’s routinely trotted out when lawmakers tout the ways in which Rhode Island has addressed climate change.

In reality, the

legislation is little more than political window dressing.

It created a mirage of

political action. Lawmakers use it as a shield, to deflect having to do

anything that truly addresses the mounting pressures caused by a changing

climate.

The 2014 law created the

Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (ecoRI News published an in-depth look

at the EC4 in January), and the General Assembly asked this unpaid board — with

zero staff to conduct research or handle administrative tasks, with no funding,

and with no authority — to address the complexities of climate change.

The law also called for

the creation of an Advisory Board “charged

with advising the EC4 on all matters pertaining to the duties and powers of the

Council, including evaluating and making recommendations regarding plans,

programs, and strategies relating to climate change mitigation and adaptation.”

The last Advisory Board

meeting with a quorum was held in March 2017. Currently, there are six empty

seats that need to be filled by the General Assembly before the board can begin

meeting again.

Unsurprisingly, Rhode

Island has accomplished little in reducing greenhouse-gas emissions or

mitigating climate-change impacts since the Resilient Rhode Island Act was

approved.

At the most recent EC4 meeting, on June 24 — 1,796 days after the 2014 law was passed — Janet Coit, the council’s chairwoman, admitted as much. She reminded the council of agency heads that several initiatives will be needed for the state to realize its climate-adaptation and emission-reduction goals.

She noted the modeling

work being done by MIT professor John Sterman regarding global carbon

emissions.

“It demonstrates very

clearly, very quickly that if we are going to meet the levels that we committed

to in the Paris Agreement then we are going to have to do a whole lot of things

at once,” Coit told her fellow EC4 members,

all of whom have watched the occupants of the Statehouse do next to nothing

during the past five years to address climate emissions, beyond signing

unenforceable executive orders, annually holding carbon-pricing legislation for

further study, and making a promise to remain committed to the Paris Agreement.

Coit, who is the

director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), also

told the restrained EC4 that energy efficiency and decarbonization must “go

forward aggressively in all sectors if we’re going to prevent catastrophic

climate impacts.”

Such prevention is

virtually impossible, however, without significant investment in mitigation

programs and initiatives, reworking the state’s car-orientated transportation

sector, robust discussion, and plenty of political will. Rhode Island has had

plenty of meaningful climate discussions, sometimes even with members of the

Statehouse’s centralized hierarchy of political power.

The hierarchy, however,

remains narrowly focused on economic growth and the promise of jobs, mostly in

the trades sector. This singular focus largely treats climate action as an

economic burden.

Special interests have told them to wait for the free market to devise an economic solution to climate change. The waiting is sacrificing the future.

Special interests have told them to wait for the free market to devise an economic solution to climate change. The waiting is sacrificing the future.

If done justly though —

with government mandates that are enforced and stable incentives that push the

free market to respond quickly — climate mitigation and adaptation, besides

reducing carbon emissions, protecting human and environmental health, and

safeguarding the future, would create jobs and bulwark the economy.

The Resilient Rhode

Island Act created such a roadmap.

“Since 2014 there has

been a change in the amount and depth of discussions at the state level about

climate change,” said Timmons Roberts, professor of environmental studies and

sociology at Brown University who helped craft the legislation.

“We’ve also seen stronger efforts regarding information sharing and coordination by state agencies. There’s more awareness.”

“We’ve also seen stronger efforts regarding information sharing and coordination by state agencies. There’s more awareness.”

But, as Roberts and

others have noted repeatedly during the past five years, more substantial

conversations and better sharing of information haven’t reduced Rhode Island’s

carbon emissions or significantly prepared the state for the worsening impacts

of climate change.

The state’s respected lending program for fortifying municipal infrastructure such as wastewater treatment plants can’t be the crux of Rhode Island’s mitigation and adaptation initiatives.

The state’s respected lending program for fortifying municipal infrastructure such as wastewater treatment plants can’t be the crux of Rhode Island’s mitigation and adaptation initiatives.

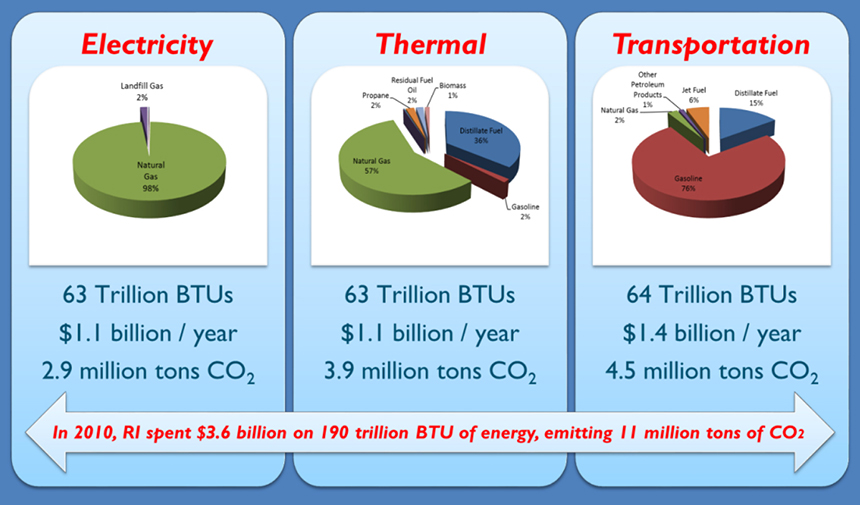

Rhode Island has set

bold targets to reduce climate emissions from all sectors of the economy,

electricity, heating, and transportation, but there’s no real pathway to get

there. (State of Rhode Island)

Another framework for action …

On June 19, 2014, on the heels of the approval of the Rhode Island Climate Risk Reduction Act, both houses of the General Assembly passed the Resilient Rhode Island Act. Lawmakers said at the time that this new law would provide a framework for state government to adaptively plan for and manage climate-change impacts.

Rep. Deb Ruggiero,

D-Jamestown, who co-sponsored the legislation, said the act has helped create a

strategy to address climate change and prepare Rhode Island for when the next

big storm hits.

“Economic resilience

depends on environmental resilience,” she said.

Four years earlier, the Rhode Island Climate Risk Reduction

Act of 2010 promised a similar resilience strategy. The act was

designed to help “move the state to an active response to climate change

impacts by identifying some of the most critical issues that will have to be

addressed, and by investigating and implementing cost-effective solutions

and/or adaptation strategies for the state and its municipalities.”

The legislation also

created the Rhode Island Climate Change Commission, which then established

three workings groups. The commission issued its first report in May 2012.

The-40 page report

reviewed key climate risks and vulnerabilities, identified current

climate-change initiatives, highlighted adaptation needs not yet met, and

outlined next steps, such as assessing risks and vulnerabilities, tracking

climate-change activities, identifying legislative priorities, and developing

an annual work plan.

It offered little in the way of bold action, and there was no ambitious path to lower emissions.

It offered little in the way of bold action, and there was no ambitious path to lower emissions.

The Resilient Rhode

Island Act of 2014 was designed to provide a comprehensive and coordinated

state response to climate change. It called for “establishing adaptive

management as a basic principle for the management of the natural resources of

the state for the benefit of the current and future generation of residents.”

The legislation also

created the EC4, which then established its own working group. Roberts is a

member of the Science and Technical Advisory Board. He said the effort has been

a “lost opportunity to push state-mandated emission-reduction targets.”

He noted such efforts underway in California, Hawaii, and New York. The EC4 issued its first report in June 2016.

He noted such efforts underway in California, Hawaii, and New York. The EC4 issued its first report in June 2016.

The 47-page report summarized the commission’s work to date, noted that both mitigation and adaptation are necessary to Rhode Island’s resilience, explained climate risks and vulnerabilities, and highlighted other climate-related reports, programs, and plans, plus a project and an executive order.

It offered little in the way of bold action, and there was no ambitious path to lower emissions.

To help mitigate climate

change, the latest act does call for state carbon emissions to be gradually

cut, from 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2020, 45 percent below 1990 levels by

2035, and 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.

DEM has said Rhode

Island is on track to meet 2020 target levels. At the moment, though, the act’s

80 percent goal is a pipe dream. Also, that 6-year-old goal is already

considered insufficient when it comes to addressing the impacts of global

warming, according to the latest science from the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration and the United Nations.

Roberts said Rhode Island

has been slow to adapt to the changing landscape of climate change.

“Unfortunately, state

agencies and the General Assembly have not caught up to the science and level

of urgency required to address climate change and the burning of fossil fuels,”

he said. “We haven’t taken adequate action to reduce emissions.”

The Resilient Rhode

Island Act was crafted with assistance from a group of Brown University

students, faculty, including Roberts, and policy experts. They partnered with

local environmental and planning organizations and gathered input from coastal

stakeholders, state agencies, and municipal governments.

The group effort

envisioned the act to: use the powers of government institutions to respond to

climate change in a comprehensive, integrated, and aggressive manner; protect

natural areas and landscape features that buffer changing climatic conditions

such as sea-level rise; integrate adaptation planning into existing plans;

update building codes to accommodate anticipated change expected during design

life; embrace the use of green infrastructure, low-impact development, and

economic diversification; ensure the protection of vulnerable populations.

Some of the law’s

mandates have been applied, most notably the increasing use of green

infrastructure, and revamped building codes. More air conditioners have been

put in senior centers. But many of the actions outlined in the legislation to

make Rhode Island more resilient are routinely ignored when it comes time to

make decisions and issue rulings.

The law made DEM the

coordinating agency for mitigation and the Department of Administration’s

Division of Statewide Planning as the lead agency on adaptation. So far their

combined efforts have accomplished little in reducing Rhode Island’s carbon

emissions. To be fair, though, it’s difficult to make progress when the

political hierarchy doesn’t offer support.

But, still nothing but

talk, talk

Last summer state officials

unveiled the Resilient Rhody plan — a collection of

information picked from some other 50 previous reports and studies.

The redundant plan, a

document highly touted by Gov. Gina Raimondo’s administration, lists five dozen

recommended actions, such as monitoring existing coastline pilot projects,

developing offshore sand sources suitable for beach replenishment, prioritizing

beaches to be re-nourished, and creating beach and barrier migration pathways

through property acquisition and relocation of structures.

Resilient Rhody also offers a host of guiding principles, such as “Equitably reduce the burden of climate change impacts with particular attention to environmental justice communities across the state,” and talks a good game — “Effectively addressing climate change needs to leverage bold emission reduction targets and adaptation measures.”

But the non-binding list

of regurgitated actions, goals, and ideas provides no clear path as to how to

make the big changes necessary to effectively address climate change.

The report doesn’t include any immediate action steps or a timeline for meeting its goals. It makes no mention of a carbon tax or of carbon pricing. It offers no funding or key resources to address the challenging problem.

The report doesn’t include any immediate action steps or a timeline for meeting its goals. It makes no mention of a carbon tax or of carbon pricing. It offers no funding or key resources to address the challenging problem.

“I don’t understand why

the governor’s administration thinks they are real climate-change champions,”

Roberts said. “They’ve taken a lukewarm level of action to address the issue.”

In early July, Raimondo

provided more lip service to Rhode Island’s fight against climate change, by

signing yet another non-binding executive order.

Led by the Division of Public Utilities and Carriers (DPUC) and the Office of Energy Resources (OER), the Heating Sector Transformation in Rhode Island effort will advance the state’s “development of clean, affordable, and reliable heating technologies.”

Led by the Division of Public Utilities and Carriers (DPUC) and the Office of Energy Resources (OER), the Heating Sector Transformation in Rhode Island effort will advance the state’s “development of clean, affordable, and reliable heating technologies.”

The order states that

the DPUC, OER, and the Rhode Island Commerce Corporation “shall engage key governmental

and non-governmental partners, including, but not limited to, the Executive

Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4), in the development of its work

products.”

“With efforts already underway to bring cleaner alternatives to the energy and transportation sectors, the heating sector is the next frontier,” OER commissioner Carol Grant is quoted in the July 8 press release that announced the governor’s 44th of 45 executive orders.

“Today’s action by the Governor commits us to looking at changes in our heating systems that help the state reach its goals of reduced emissions, working with all the stakeholders involved in this transformation.”

Rhode Island has set

bold targets to reduce climate emissions from all sectors of the economy —

electricity, heating, and transportation — but there’s no real pathway to get

there.

The state is largely relying on endless meetings, redesigned websites, an arbitrary renewable-energy goal, a group of overworked agency heads, and a hodgepodge of reports, studies, commission findings, executive orders, and recommendations to create non-binding, unenforceable wishful thinking that will magically reduce emissions.

The state is largely relying on endless meetings, redesigned websites, an arbitrary renewable-energy goal, a group of overworked agency heads, and a hodgepodge of reports, studies, commission findings, executive orders, and recommendations to create non-binding, unenforceable wishful thinking that will magically reduce emissions.

Meanwhile, the hierarchy

talks a good game but is content to kick the problem into the future while it

placates special interests in the present.

“There’s a willingness

to support renewables but there is no willingness to even talk about shutting

down fossil fuels,” Roberts said. “The fossil-fuel industry has a death grip on

the General Assembly.”