By TIM FAULKNER/ecoRI News staff

|

| A tidal current platform in the Cape Cod Canal will soon test its first underwater turbine. (Marine Renewable Energy Collaborative) |

Efforts to generate electricity from

waves and tidal currents have slowed in southern New England, as offshore wind

power takes a commanding lead in the renewable-energy portion of the so-called

“blue economy.”

In recent years, tidal- and

wave-energy programs at Brown University, University of Massachusetts

Dartmouth, and the University of Rhode Island have curtailed their research and

commercial collaborations.

At Brown, the Leading Edge project has shifted from an

academic and commercial venture to a school-based laboratory-research project.

Engineering students designed oscillating hydrofoils that generate electricity from rectangular blades that lift and rotate in strong currents.

Faculty leaders, however, have gone to other schools or are on sabbatical, thereby halting commercial partnerships.

Engineering students designed oscillating hydrofoils that generate electricity from rectangular blades that lift and rotate in strong currents.

Faculty leaders, however, have gone to other schools or are on sabbatical, thereby halting commercial partnerships.

The program was funded by the

federal Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy

(APRA-E) program, which supports energy initiatives that private investors

consider too risky.

Leading Edge partnered with

Portsmouth, R.I.-based BluSource Energy Inc. to build and test

underwater turbines in the Taunton River and at the Massachusetts Maritime

Academy at the entrance of the Cape Cod Canal.

Tom Derecktor, CEO of BluSource, said the turbine succeeded in producing uninterrupted electricity, something wind and solar can’t promise. But he noted the challenges of scaling hydrokinetic power for commercial production.

Large energy systems require open water or a river with a strong current, free from ship traffic and debris, conditions hard to find in the Northeast. Most currents with the desired speed of 4 knots or more are too far from population centers to host a permanent power system.

Still, Derekotor believes that tidal

energy can achieve scale in other parts of the country.

“There’s a lot of potential there,

but it requires a lot funding to take it to the next level,” he said.

Congress may help by increasing

funding for the APRA-E program, but Trump opposes the program and has

tried, unsuccessfully, to eliminate its funding.

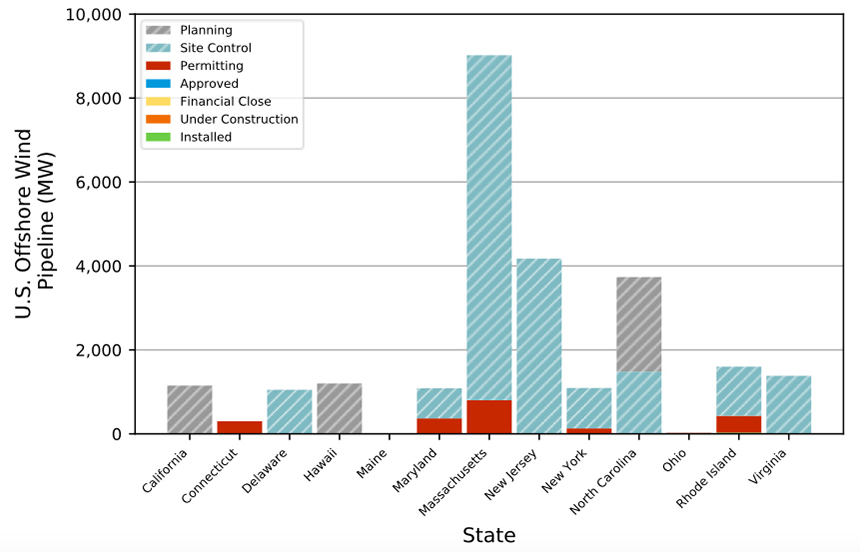

Offshore wind-energy development by

state. (Department of Energy)

Meanwhile, offshore wind power is

taking off, with some 25 gigawatts of projects proposed across the country,

much of it in the Northeast, according to the Department of

Energy.

More then 10 gigawatts is planned for Massachusetts and Rhode Island waters, thanks to southern New England's large, windy, and relatively shallow offshore regions — all within range of millions of energy customers.

More then 10 gigawatts is planned for Massachusetts and Rhode Island waters, thanks to southern New England's large, windy, and relatively shallow offshore regions — all within range of millions of energy customers.

There is still hope for harnessing

energy from currents and waves. In 2014, UMass-Dartmouth closed its Marine

Renewable Energy Center, prompting the energy program to reorganize as the Marine Renewable Energy Collaborative (MRECo). The

nonprofit switched from its academic initiative to focus on public outreach,

promotion, and equipment testing.

MRECo’s executive director, John

Miller, said there isn’t adequate financial support to make tidal and wave

projects financially viable, especially as federal dollars have shifted to wave-energy

testing on the West Coast, such as the PacWave project off

the coast of Oregon.

“It’s a tough business,” Miller

said. “The whole business is 10 to 15 years behind where offshore wind is.”

Nevertheless, MRECo is testing a

range of marine-industry products. The organization recently concluded a study

that determined that current for the proposed Muskeget Channel tidal

installation between Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard lacks the velocity to support

the latest tidal-energy systems.

In 2017, MRECo installed the Bourne

Tidal Test Site (BTTS) in the Cape Cod Canal. Miller noted that the $300,000

steel platform was a bargain to build compared to more elaborate facilities off

the coast of Scotland and in the Bay of Fundy in Canada that cost $30 million

apiece.

Within a year, BTTS expects to test

its first underwater turbine, a device for the start-up company Littoral

Power Systems of Fall River, Mass. BTTS has hosted other marine

equipment, including commercial fishing nets and soon will gather data for

aquatic sensors that monitor microplastics and algae linked to toxic blooms.

MRECo is seeking $200,000 to upgrade

the power and internet capability of BTTS to accommodate testing of additional

marine sensors and instruments.

At URI, the ocean-energy research

labs and indoor wave tank have broadened their study areas to include the

offshore wind industry.

Professor M. Reza Hashemi said wave

and tidal power are some of the oldest forms of energy but have yet to be

proven commercially viable in New England, primarily because water currents

aren’t strong enough.

“There is hope, but it needs a lot

help,” Hashemi said.

Wave and tidal energy are more promising

on the West Coast and in the United Kingdom, where the currents are much

stronger, he said.

But local tidal- and wave-energy

efforts haven’t stopped. The massive tides in the Gulf of Maine and North

Atlantic are drawing demonstration projects supported by research from URI and

the University of New Hampshire, among others.

Hashemi also co-authored a textbook about wind,

tidal, and wave energy. For now, he is conducting research on the impacts of

hurricanes on wind turbines.

But Hashemi and URI remain dedicated to hydrokinetic energy. The university recently received $148,000 from The Champlin Foundation for a new ocean-energy flume, a type of indoor wave tank designed for testing small-scale wave- and tidal-energy devices.

But Hashemi and URI remain dedicated to hydrokinetic energy. The university recently received $148,000 from The Champlin Foundation for a new ocean-energy flume, a type of indoor wave tank designed for testing small-scale wave- and tidal-energy devices.

“Wave and tidal energy are still at

the early stages of development,” Hashemi said. “They are not yet at the

commercial stage.”