Could

graphene-lined clothing prevent mosquito bites?

Brown

University

|

| Researchers created an experimental setup to see if graphene could prevent mosquito bites. |

But a new study by Brown University researchers finds a surprising new use for the material: preventing mosquito bites.

In

a paper published

in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers showed that

multilayer graphene can provide a two-fold defense against mosquito bites.

The ultra-thin yet strong material acts as a barrier that mosquitoes are unable to bite through. At the same time, experiments showed that graphene also blocks chemical signals mosquitoes use to sense that a blood meal is near, blunting their urge to bite in the first place.

The findings suggest that clothing with a graphene lining could be an effective mosquito barrier, the researchers say.

The ultra-thin yet strong material acts as a barrier that mosquitoes are unable to bite through. At the same time, experiments showed that graphene also blocks chemical signals mosquitoes use to sense that a blood meal is near, blunting their urge to bite in the first place.

The findings suggest that clothing with a graphene lining could be an effective mosquito barrier, the researchers say.

“Mosquitoes

are important vectors for disease all over the world, and there’s a lot of

interest in non-chemical mosquito bite protection,” said Robert Hurt,a

professor in Brown’s School of Engineering, leader of Brown's Superfund

Research Program and senior author of the paper.

“We had been working on fabrics that incorporate graphene as a barrier against toxic chemicals, and we started thinking about what else the approach might be good for. We thought maybe graphene could provide mosquito bite protection as well.”

“We had been working on fabrics that incorporate graphene as a barrier against toxic chemicals, and we started thinking about what else the approach might be good for. We thought maybe graphene could provide mosquito bite protection as well.”

To find out if it would work, the researchers recruited some brave participants willing to get a few mosquito bites in the name of science. The participants placed their arms in a mosquito-filled enclosure so that only a small patch of their skin was available to the mosquitoes for biting. The mosquitoes were bred in the lab so they could be confirmed to be disease-free.

The

researchers compared the number of bites participants received on their bare

skin, on skin covered in cheesecloth and on skin covered by a graphene oxide

(GO) films sheathed in cheesecloth. GO is a graphene derivative that can be

made into films large enough for macro-scale applications.

It was readily apparent that graphene was a bite deterrent, the researchers found. When skin was covered by dry GO films, participants didn’t get a single bite, while bare and cheesecloth-covered skin was readily feasted upon.

What was surprising, the researchers said, was that the mosquitoes completely changed their behavior in the presence of the graphene-covered arm.

“With

the graphene, the mosquitoes weren’t even landing on the skin patch — they

just didn’t seem to care,” said Cintia Castillho, a Ph.D. student at Brown and

the study’s lead author.

“We had assumed that graphene would be a physical barrier to biting, through puncture resistance, but when we saw these experiments we started to think that it was also a chemical barrier that prevents mosquitoes from sensing that someone is there.”

“We had assumed that graphene would be a physical barrier to biting, through puncture resistance, but when we saw these experiments we started to think that it was also a chemical barrier that prevents mosquitoes from sensing that someone is there.”

To

confirm the chemical barrier idea, the researchers dabbed some human sweat onto

the outside of a graphene barrier. With the chemical ques on the other side of

the graphene, the mosquitoes flocked to the patch in much the same way they

flocked to bare skin.

Other

experiments showed that GO can also provide puncture resistance — but not all

the time.

Using a tiny needle as a stand-in for a mosquito’s proboscis, as well as computer simulations of the bite process, the researchers showed that mosquitoes simply can’t generate enough force to puncture GO.

But that only applied when the GO is dry. The simulations found that GO would be vulnerable to puncture when it was saturated with water. And sure enough, experiments showed that mosquitoes could bite through wet GO. However, another form of GO with reduced oxygen content (called rGO) was shown to provide a bite barrier when both wet and dry.

Using a tiny needle as a stand-in for a mosquito’s proboscis, as well as computer simulations of the bite process, the researchers showed that mosquitoes simply can’t generate enough force to puncture GO.

But that only applied when the GO is dry. The simulations found that GO would be vulnerable to puncture when it was saturated with water. And sure enough, experiments showed that mosquitoes could bite through wet GO. However, another form of GO with reduced oxygen content (called rGO) was shown to provide a bite barrier when both wet and dry.

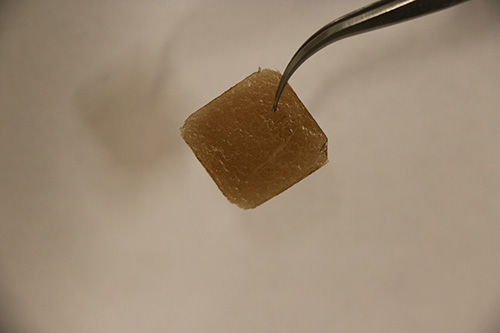

|

| A graphene oxide film was shown to prevent mosquito bites when dry. |

That’s because GO has a distinct advantage over rGO when it comes to wearable technology.

“GO

is breathable, meaning you can sweat through it, while rGO isn’t,” Hurt said.

“So our preferred embodiment of this technology would be to find a way to stabilize GO mechanically so that is remains strong when wet. This next step would give us the full benefits of breathability and bite protection.”

“So our preferred embodiment of this technology would be to find a way to stabilize GO mechanically so that is remains strong when wet. This next step would give us the full benefits of breathability and bite protection.”

All

told, the researchers say, the study suggests that properly engineered graphene

linings could be used to make mosquito protective clothing.

Other

co-authors on the study were Dong Li, Muchun Liu, Yue Liu and Huajian Gao. The

study was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences,

Superfund Research Program, and the National Science Foundation (CMMI-1634492).