Elizabeth Outka, University of Richmond

|

| Did mass graves in the influenza pandemic help give rise to the living dead? Tithi Luadthong/Shutterstock.com |

Zombies have lurched to the center of Halloween culture, with costumes proliferating as fast as the monsters themselves. This year, you can dress as a zombie prom queen, a zombie doctor – even a zombie rabbit or banana. The rise of the living dead, though, has a surprising link to another recurring October visitor: the influenza virus.

One hundred years ago, 1919 saw the end of one of the worst plagues in human history: the deadly 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. The pandemic was a true horror show, with 50-100 million people dying and millions more infected. The United States alone lost more people in the pandemic than it lost in all the 20th- and 21st-century wars, combined.

This was no ordinary flu virus: It killed young adults in high numbers, and it came with grisly side effects, like massive bleeding from the nose, mouth and ears. It could damage the nervous and respiratory systems and could cause violent derangement, delirium and – in its aftermath – profound lethargy and suicidal depression.

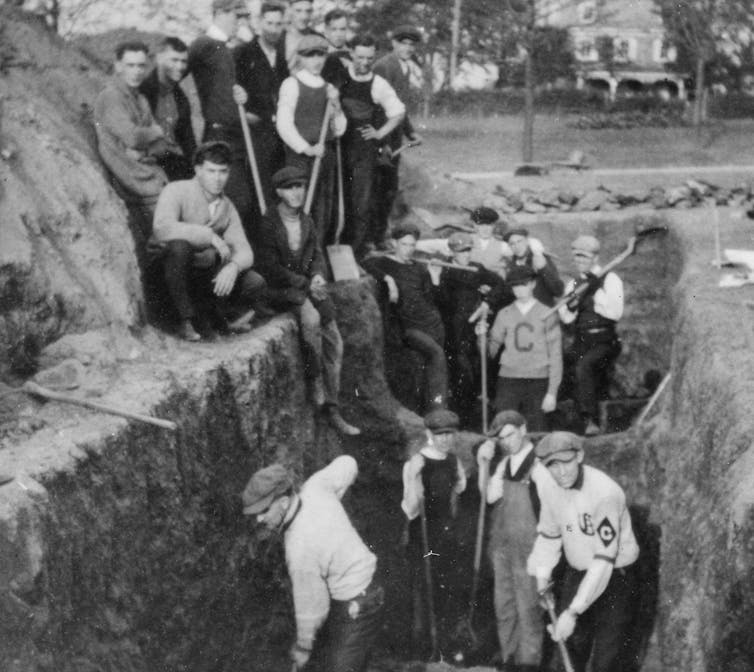

The pandemic turned communities into haunted landscapes. Coffins ran out as bodies piled up everywhere. Stores, theaters and schools were closed, and wagons were pulled through the streets to collect corpses. Funerals were often impossible to organize, and across the country, mass graves were dug to accommodate the many dead.

A literature professor, I have written about the flu’s surprising connection to zombies, spiritualism and poems like T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” in my new book, “Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature.”

The zombie connection

|

| Seminarians from St. Charles Borromeo of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia dig a mass grave at Holy Cross Cemetery sometime in Oct. 21-24, 1919, for victims of the flu pandemic. The photographer wrote in his journal that steam shovels eventually had to be utilized, presumably because of the vast number of bodies. Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, CC BY-SA |

Seabrook wrote, often in starkly racist terms, of various ceremonies, traditions and stories he had gathered in Haiti. He included an account of the zombie figure, which he described as a resurrected corpse raised from the dead by a master figure and forced to do enslaved labor. Depictions of such zombies soon found their way into popular movies like “White Zombie” (1932) or “Ouanga” (1936).

A different strain of zombie-like creatures, however, had emerged earlier in the work of horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. These zombies anticipate the ones George Romero would later depict in films like “Night of the Living Dead”: bloody, lurching, disheveled corpses intent on infecting the living and hungry for human flesh. A perfect incubator for these “viral zombies” were the grisly experiences the influenza pandemic brought to every community.

Lovecraft’s world of corpses

|

| H.P. Lovecraft (Wikipedia). He lies buried in Swan Point Cemetery in Providence |

As one local witness remembered, “all around me people were dying… . [and] funeral directors worked with fear… . Many graves were fashioned by long trenches, bodies were placed side by side”; the pandemic, the witness laments, was “leaving in its wake countless dead, and the living stunned at their loss” (letter by Russell Booth; Collier Archives, Imperial War Museum, London).

Lovecraft channeled this climate into his stories of the period – producing corpse-filled tales with infectious atmospheres from which sprang lurching, flesh-eating invaders who left bloody corpses in their wake.

In his story “Herbert West: Reanimator,” for example, Lovecraft creates a ghoulish doctor intent on reanimating newly dead corpses. A pandemic arrives that offers him fresh specimens – and that echoes the flu scenes of mass graves, overworked doctors and piles of bodies.

When the head doctor of the hospital dies in the outbreak, Dr. West reanimates him, producing a proto-zombie figure that escapes to wreak havoc on the town. The living dead doctor lurches from house to house, ravaging bodies and spreading destruction, a monstrous, visible version of what the flu virus had done worldwide.

Infection, prejudice and the viral zombie

|

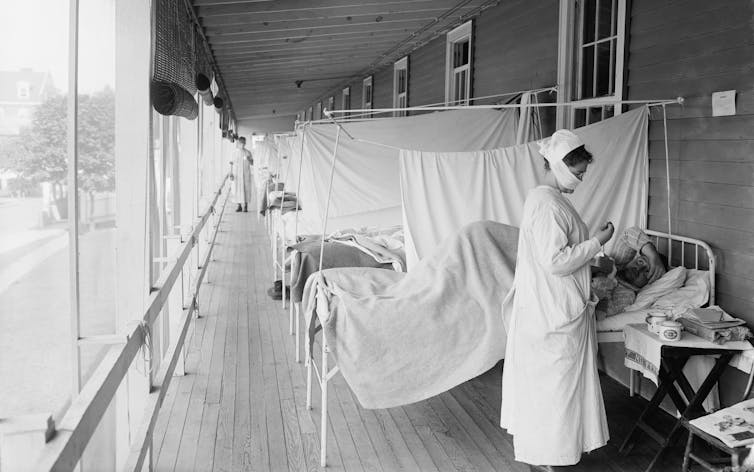

| Nurses treat flu patients at Walter Reed Hospital during the height of the 1918-1919 flu pandemic. Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com |

Even before the outbreak, Lovecraft believed that foreign hordes were infecting the Aryan race generally, weakening the bloodlines.

These xenophobic anxieties weave their way into his stories, as contagion and pandemic-soaked atmospheres blend into racist fears of immigrants and nonwhite invaders.

Indeed, many of his stories are unwitting templates for how prejudicial fears may be problematically amplified at moments of crisis. Such fears are evoked and often critiqued in later depictions of viral zombie hordes, such as the infectious monsters of Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead” and the film’s subtle commentary on race, when the white police force mistakes the main African American character for a viral zombie.

Our fears as monsters

Lovecraft’s proto-zombies also provided a strange compensation for some of the pandemic’s worst memories. Like the flu virus, these monsters consumed the flesh of the living, spread blood and violence, and acted without cause or explanation.

Lovecraft assures his readers that these monsters are far worse than anything they saw in World War I or in the pandemic – the defining tragedies of the era. Unlike the virus, though, these monsters could be seen, stopped, killed – and reburied. Every decade seems to need its own zombie, and Lovecraft offered his readers a version that spoke deeply to the anxieties of his moment.

While you may not be prepared for a zombie apocalypse this October, you can still prepare for the coming flu season. Along with your zombie banana costume, be sure to get your flu shot.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]

Elizabeth Outka, Associate Professor of English Literature, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.