Tom Wickizer, The Ohio State University; Evan V. Goldstein, The Ohio State University, and Laura Prater, The Ohio State University

|

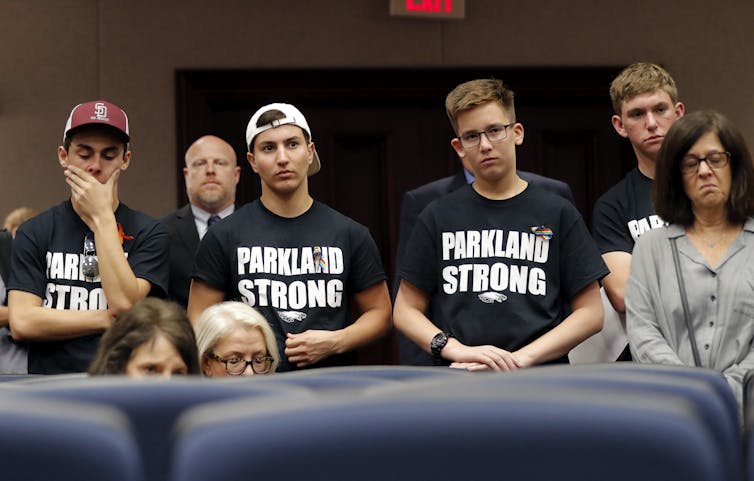

| Marjory Stoneman Douglas students gather in the Florida state Capitol in Tallahassee Feb. 21, 2018 to confront legislators about stricter gun laws. Gerald Herbert/AP Photo |

When people think of firearm death, they tend to focus on mass shootings such as the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut; the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida; and the very recent mass shootings in El Paso, Texas. and Dayton, Ohio. Although mass shootings happen frequently, research suggests that they account for less than 0.2% of all homicides in the U.S.

Suicide by guns accounts for a much greater loss of life than murder. In 2017, 39,773 people died from firearms. Murder accounted for 37% of these deaths. Law enforcement and accidental shootings accounted for about for 3% of the deaths. The remaining 60% of firearm deaths resulted from suicide.

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among U.S. adults and the second leading cause of death among teens. The majority of suicides are completed using a firearm.

There’s been a lot discussion recently about the role that mental illness plays in shooting deaths, especially firearm suicide.

As health services researchers from The Ohio State University College of Public Health, we analyzed firearm suicide and the capacity of states to provide behavioral health care services: that is, mental health services and substance disorder services. We wanted to know if suicide deaths by guns were lower in states that offered more expansive behavioral health care.

Deaths by suicide on the riseSince 2005, the firearm suicide rate has increased by 22.6%, compared to a 10.3% rise in the firearm homicide rate.

Without question, the U.S. has the most firearm deaths and firearm suicides compared to all other high-income, developed countries. The U.S. firearm homicide rate is more than 25 times higher than other high-income developed countries, while the firearm suicide rate is eight times higher.

A number of factors contribute to America’s high firearm death rate, but one factor unique to America stands out – the widespread availability of guns.

The high prevalence of gun ownership in the U.S. contributes to the burden of firearm-related injury. Estimates indicate over 390 million guns are owned in the U.S. by approximately one-third of the nation’s population, which amounts to 120.5 guns owned for every 100 persons in the country. In contrast, there are 34.7 guns owned per 100 persons in Canada. There are comparatively far fewer firearm homicides in Canada than in the U.S.

Firearm suicide and behavioral health care

Using data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other government agencies, we performed a detailed statistical analysis to examine firearm suicide rates from 2005 to 2015 in each state in relation to the size of behavioral health care workforce and the number of substance disorder treatment facilities.

In a study published in Health Affairs Oct. 7, we found a statistically significant 10% increase in the behavioral health care workforce was associated with a 1.2% decrease in the firearm suicide rate.

We controlled for variables such as the unemployment rate, race, gender and population size, among others. Increasing the workforce by 40%, a change that could potentially take significant time and resources, would perhaps lead to a reduction in the firearm suicide rate of only 4.8%.

Increasing the capacity to provide needed behavioral health care could be a costly approach to reducing firearm suicides.

Based on our statistical analysis, and taking account of the salaries for mental health professionals, it could cost as much as US$15 million to increase the size of Ohio’s behavioral health care workforce enough to prevent one firearm suicide.

Policy implications and a path forward

|

| Mourners gather at the funeral for Margie Reckard, 63, on Aug. 16, 2019, who was killed in the El Paso, Texas shooting rampage. Russell Contreras/AP Photo |

Based on our research, we believe that several concrete steps could be taken to foster preventive measures.

First, although increasing access to mental health care is necessary for a variety of compelling reasons, our findings suggest that strengthening mental health services won’t reduce firearm violence.

Rather, action may be needed at the federal, state and local levels to strengthen laws and regulations shown to promote gun safety and prevent firearm deaths. Other countries, in particular Australia and New Zealand, responded forcefully to mass shooting events when they occurred and adopted regulatory measures to protect their citizens against gun violence.

Second, the medical and public health communities do more to prevent firearm suicide and deaths.

Individual physicians working in their clinical roles could perform screenings to identify persons with mood disorders who are at risk for suicide. The medical community and public health community, acting through their professional associations, could advocate firearm safety.

Third, the Dickey Amendment, which was passed in 1996, and related policies have stifled federal funding for gun violence research. We believe that Congress should repeal the law and related policies.

There is a critical need to conduct research to improve understanding about the risk factors for firearm suicide and gun violence and about the measures that could be taken to combat the firearm death epidemic afflicting our communities.

The substantial majority of the public, both gun owners and non-gun owners, favor stronger regulation for the purchase of guns and for their use and storage. Research shows having firearms available and keeping them in the home are strong risk factors for completed suicide, especially among adolescents.

So far the country has made little meaningful progress in combating the epidemic of firearm suicide and firearm deaths.

Data show the problem is getting worse, not better. Finding effective approaches to reducing the problem of firearm suicide and gun violence will require that the country become more politically unified in its willingness to recognize the scope and nature of the problem. There seems little excuse for continued inaction.

[ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day. ]

Tom Wickizer, Chair and Professor, Public Health, The Ohio State University; Evan V. Goldstein, Doctoral candidate, The Ohio State University, and Laura Prater, Postdoctoral Fellow, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.