Lower

temperatures used in 'energy saver' washing machines may not be killing all

pathogens

American

Society for Microbiology

For

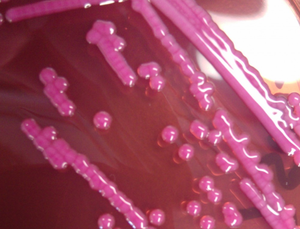

the first time ever, investigators have identified a washing machine as a

reservoir of multidrug-resistant pathogens. The pathogens, a single clone

of Klebsiella oxytoca, were transmitted repeatedly to newborns in a

neonatal intensive care unit at a German children's hospital.

For

the first time ever, investigators have identified a washing machine as a

reservoir of multidrug-resistant pathogens. The pathogens, a single clone

of Klebsiella oxytoca, were transmitted repeatedly to newborns in a

neonatal intensive care unit at a German children's hospital.

The transmission

was stopped only when the washing machine was removed from the hospital. The

research is published this week in Applied and Environmental

Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

"This

is a highly unusual case for a hospital, in that it involved a household type

washing machine," said first author Ricarda M. Schmithausen, PhD.

Hospitals normally use special washing machines and laundry processes that wash

at high temperatures and with disinfectants, according to the German hospital

hygiene guidelines, or they use designated external laundries.

The

research has implications for household use of washers, said Dr. Schmithausen,

Senior Physician, Institute for Hygiene and Public Health, WHO Collaboration

Center, University Hospital, University of Bonn, Germany.

Water temperatures

used in home washers have been declining, to save energy, to well below 60°C

(140°F), rendering them less lethal to pathogens. Resistance genes, as well as

different microorganisms, can persist in domestic washing machines at those

reduced temperatures, according to the report.

"If elderly people requiring nursing care with open wounds or bladder catheters, or younger people with suppurating injuries or infections live in the household, laundry should be washed at higher temperatures, or with efficient disinfectants, to avoid transmission of dangerous pathogens," said Martin Exner, MD, Chairman and Director of the Institute for Hygiene and Public Health, WHO Collaboration Center, University Hospital/University of Bonn.

"This is a growing challenge for hygienists, as the number of people

receiving nursing care from family members is constantly increasing."

At

the hospital where the washing machine transmitted K. oxytoca,

standard screening procedures revealed the presence of the pathogens on infants

in the ICU. The researchers ultimately traced the source of the pathogens to

the washing machine, after they had failed to find contamination in the

incubators or to find carriers among healthcare workers who came into contact

with the infants.

The

newborns were in the ICU due mostly to premature birth or unrelated

infection.The clothes that transmitted K. oxytoca from the

washer to the infants were knitted caps and socks to help keep them warm in

incubators, as newborns can quickly become cold, even in incubators, said Dr.

Exner.

The

investigators assume that the pathogens "were disseminated to the clothing

after the washing process, via residual water on the rubber mantle [of the

washer] and/or via the final rinsing process, which ran unheated and

detergent-free water through the detergent compartment," implicating the

design of the washers, as well as the low heat, according to the report.

The

study implies that changes in washing machine design and processing are

required to prevent the accumulation of residual water where microbial growth

can occur and contaminate clothes.

However,

it still remains unclear how, and via what source the pathogens got into the

washing machine.

The

infants in the intensive care units (ICU) were colonized, but not infected

by K. oxytoca. Colonization means that pathogens are harmlessly

present, either because they have not yet invaded tissues where they can cause

disease, or because the immune system is effectively repelling them.

The

type of multidrug resistance in the K. oxytoca is caused by

extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL). These enzymes disable antibiotics

called beta lactams. The most common types of bacteria producing ESBLs are Escherichia

coli, and bacteria from the genus Klebsiella.