How

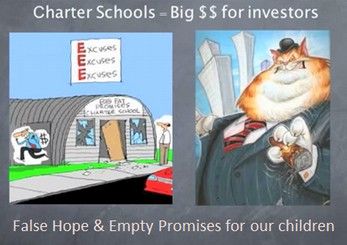

Charter-School Billionaires Corrupt School Leadership

It’s rare when

goings-on in Kansas City, Missouri schools make national headlines, but in 2011

the New York Times reported on

the sudden departure of the district’s superintendent John Covington, who

resigned unexpectedly with only a 30-day notice.

It’s rare when

goings-on in Kansas City, Missouri schools make national headlines, but in 2011

the New York Times reported on

the sudden departure of the district’s superintendent John Covington, who

resigned unexpectedly with only a 30-day notice.

Covington, who had

promised to “transform” the

long-troubled district, “looked like a silver bullet” for all the district’s

woes, according to

the Los Angeles Times.

He had, in a little more than two years, quickly set about remaking the district’s administrative staff, closing nearly half the schools, revamping curriculum, and firing teachers while hiring Teach for America recruits.

He had, in a little more than two years, quickly set about remaking the district’s administrative staff, closing nearly half the schools, revamping curriculum, and firing teachers while hiring Teach for America recruits.

The story of

Covington’s sudden departure caught the attention of coastal papers no doubt

because it perpetuated a common media narrative about

hard-charging school leaders becoming victims of school districts’ supposed

resistance to change and the notoriously short tenures of superintendents.

Although there may be

some truth to that narrative, the main reason Covington left Kansas City was

not because he was pushed out by job stress or an obstinate resistance. He left

because a rich man offered him a job.

Following the

reporting by the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times about Covington’s

unexpected resignation, news emerged from the Kansas City Star that days after he

resigned, he took a position as the first chancellor of the Education

Achievement Authority of Michigan, a new state agency that, according to

Michigan Radio, sought “radical” leadership

to oversee low-performing schools in Detroit.

But at the time of Covington’s departure, it seemed no outlet could have described the exact circumstances under which he was lured away.

That would come out years later in the Kansas City Star where reporter Joe Robertson described a conversation with Covington in which he admitted that squabbles with board members “had nothing to do” with his departure. What caused Covington’s exit, Robertson reported, was “a phone call from Spain.”

That call, Covington told Robertson, was what led to Covington’s departure from Kansas City—because it brought a message from billionaire philanthropist and major charter school booster Eli Broad. “John,” Broad reportedly said, “I need you to go to Detroit.”

It wasn’t the first time Covington, who was a 2008 graduate of a prestigious training academy funded through Broad’s foundation (the Broad Center), had come into contact with the billionaire’s name and clout. Broad was also the most significant private funder of the new Michigan program he summoned Covington to oversee, providing more than $6 million in funding from 2011 to 2013, according to the Detroit Free Press.

But Covington’s story

is more than a single instance of a school leader doing a billionaire’s

bidding. It sheds light on how decades of a school reform movement, financed by

Broad and other philanthropists and embraced by politicians and policymakers of

all political stripes, have shaped school leadership nationwide.

Charter advocates and

funders—such as Broad, Bill Gates,

some members of the Walton Family Foundation, John Chubb,

and others who fought strongly for schools to adopt the management practices of

private businesses—helped put into place a school leadership network whose

members are very accomplished in advancing their own careers and the interests

of private businesses while they rankle school boards, parents, and teachers.

Our Schools

interviewed Thomas Pedroni, an associate professor of curriculum studies at

Wayne State University in Detroit and a longtime observer of reform efforts in

Detroit and Michigan.

According to Pedroni, the school leadership network, especially in large, urban school districts, wields a cartel-like influence that seeks to wrestle school governance away from democratically elected school boards and outsource district management to private contractors, often in the ed-tech industry.

These businesses frequently have close associations with colleagues in school reform circles that are directly connected to the Broad network or seek the network’s favor.

The actions of these

leaders are often disruptive to communities, as school board members chafe at

having their work undermined, teachers feel increasingly removed from decision

making, and local citizens grow anxious at seeing their taxpayer dollars

increasingly redirected out of schools and classrooms and into businesses whose

products and services are of questionable value.

The Broad Factor

In her seminal 2011

essay in Dissent magazine, Joanne Barkan described Broad’s

influence on education as one of the “Big Three” funders—along with the Bill

and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation—whose “size and

clout” have been instrumental in driving the education reform movement’s success.

Through his private foundation, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, Broad has directed huge sums of money to initiate dramatic changes to school systems and educational leadership.

Through his private foundation, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, Broad has directed huge sums of money to initiate dramatic changes to school systems and educational leadership.

With a mission to “advance entrepreneurship” in

education and other fields, Broad’s education donations have focused, according to

the organization’s 2010 annual report, on “two issues Eli Broad knew well from

his days in business: governance and management—school board to

superintendent.”

Broad’s efforts to

transform school governance and management include conducting a training center for

school leaders; advocating for school governance models that

emphasize business methodologies rather than democratic engagement;

circumnavigating traditional teacher preparation programs by funding Teach for America;

and supporting charter schools and organizations and political candidates that

promote charters.

In 2011, when

Covington was in Kansas City, leaders of the nation’s three biggest

districts—New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago—were products of the Broad

pipeline, reported Education

Week, and “21 of the nation’s 75 largest districts” had “superintendents or

other highly placed” administrators who had “undergone Broad training.”

Upon Broad’s

retirement in 2017, “experts” quoted in

Education Week contended “his legacy in reshaping how private money can influence

policy, and the politics around those ideas will extend into the foreseeable

future.”

In describing Broad’s

impact on school leadership, Barkan quoted

a memorable phrase from Frederick Hess, an education scholar at the American

Enterprise Institute, a reform-minded advocacy organization.

Hess asserted that while most philanthropists focus on funding “programs,” Broad believed in creating “pipelines … for talented practitioners to advance and influence” how schools are managed and governed.

Hess asserted that while most philanthropists focus on funding “programs,” Broad believed in creating “pipelines … for talented practitioners to advance and influence” how schools are managed and governed.

“Once Broad alumni are

working inside the education system, they naturally favor hiring other

Broadies,” Barkan added.

Broad’s investments in

education reform were about redesigning schools “to function like corporate

enterprises,” wrote education historian Diane Ravitch in her 2010 bestselling

book The Death and Life of the

Great American School System.

Acting more

“corporate” was often interpreted by reform-driven school leaders to adopt a

corporate language infused with business principles such as resource

maximization, market competition, and getting a return on education investment.

To make this business-minded agenda more palatable to the education community, practitioners of the reform creed tend to wrap their management practices in the rhetoric of being “about kids,” with promises to promote “equity” and “student-centered learning.”

To make this business-minded agenda more palatable to the education community, practitioners of the reform creed tend to wrap their management practices in the rhetoric of being “about kids,” with promises to promote “equity” and “student-centered learning.”

But regardless of

their intentions, reform-minded leaders, once in positions of power, have

frequently been criticized for being “hostile to teachers,” “dictatorial,” and “anti-democratic.”

Also, despite their

high-minded intentions, reform-driven school leaders, including those in the

Broad community, don’t always have a clear, consistent track record of

accomplishments.

Most research studies on the impact school superintendents have on school performance and student achievement have found negligible results, and there are few to none independent research studies on the effectiveness of Broad leaders.

Most research studies on the impact school superintendents have on school performance and student achievement have found negligible results, and there are few to none independent research studies on the effectiveness of Broad leaders.

Further, the influence

of the reform movement Broad helped enable is generally considered to be on the

wane. The grab bag of policies the movement promoted—including high-stakes testing, curriculum standards,

test-based teacher evaluation

systems, and charter schools—is

far from being uniformly successful. And many former acolytes of

the cause increasingly consider the reform movement as over and

a mostly failed endeavor.

But what Broad has

done to shape school leadership is likely to stick, not because it has proven

to help turn around troubled schools, but because it’s turned school leadership

into a profession that does what corporations often do best: advance personal

careers and help create higher profits for private enterprises.

A School Leadership ‘Cartel’

Due to the influence

of the reform movement, school leadership has undergone a “reorganization,”

according to Thomas Pedroni of Wayne State University in Detroit.

In a phone

conversation, Pedroni called school leaders who practice “market-based”

approaches advocated by Broad and other reformers another effort aimed at

“privatizing as much of the public system as possible.”

While the history of

efforts to privatize public education extends decades

before the advent of the reform movement, Pedroni believes the reform ideology

driven by Broad and other philanthropists has rebranded the effort.

“In the educational

privatization sphere, there are two factions,” he explained. “There is the Wild

West market faction, which opposes taxation and public institutions and wants

government to step completely out of the way once it has created the conditions

for so-called educational markets.”

This faction, according to Pedroni, is most prominently represented by current U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, a native of Michigan Pedroni had long followed prior to her ascendency to the Trump administration.

Like Broad, DeVos used millions of dollars of her family’s money to remake public education systems to allow parents to use public funds to pay for private school tuition and to oppose attempts to regulate the private charter school industry.

“The other” faction

pushing privatization, Pedroni said, is a bit different and not as aligned with

conservative politics.

That faction seeks to

“use the state as a regulatory body to control entry to the market,” Pedroni

said.

This faction supports taxing the populace to pay for public schools, and they want to keep funding in the public system. But they want to limit who can make decisions about how that money is spent and to keep those decisions behind a managerial curtain.

This faction supports taxing the populace to pay for public schools, and they want to keep funding in the public system. But they want to limit who can make decisions about how that money is spent and to keep those decisions behind a managerial curtain.

“I refer to the latter

faction as more of the cartel system of market control,” he said.

Pedroni sees Broad as

very much falling into the latter of the two camps. For instance, although

Broad is a huge fan of charter schools, he also sent a

letter to U.S. senators asking them to vote against DeVos when she was

nominated to be secretary.

While members of an

industrial cartel work to increase their collective profits by means of

price-fixing, limiting supply, or other restrictive practices, Broad-inspired

school leaders are seen by Pedroni to be working to increase their collective

power by disrupting community-based governance, creating mutually beneficial

relationships with private businesses, and limiting the supply of leadership

ideas that are acceptable for transforming schools.

This is the first of a two-part

article produced by Our Schools,

a project of the Independent Media Institute.