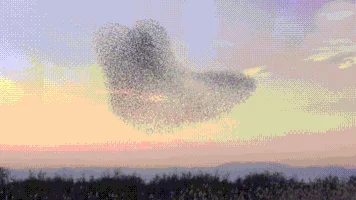

Birds

of a feather flock together, but how do they decide where to go?

American

Institute of Physics

Coordinated

behavior is common in a variety of biological systems, such as insect swarms,

fish schools and bacterial colonies.

Coordinated

behavior is common in a variety of biological systems, such as insect swarms,

fish schools and bacterial colonies. But the way information is spread and decisions are made in such systems is difficult to understand.

A

group of researchers from Southeast University and China University of Mining

and Technology studied the synchronized flight of pigeon flocks. They used this

as a basis to explain the mechanisms behind coordinated behavior, in the

journal Chaos, from AIP Publishing.

"Understanding

the underlying coordination mechanism of these appealing phenomena helps us

gain more cognition of the world where we live," said author Duxin Chen,

an assistant professor at Southeast University in China.

"Understanding

the underlying coordination mechanism of these appealing phenomena helps us

gain more cognition of the world where we live," said author Duxin Chen,

an assistant professor at Southeast University in China.

Previously,

it was believed that coordinated behavior is subject to three basic rules:

Avoid collision with your peers, match your speed and direction of motion with

the rest of the group, and try to stay near the center.

The scientists examined how every individual pigeon within a flock is influenced by the other members and found the dynamics are not so simple.

The scientists examined how every individual pigeon within a flock is influenced by the other members and found the dynamics are not so simple.

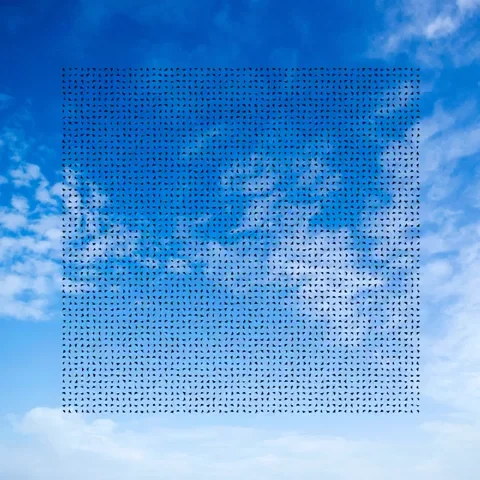

The

researchers studied the flights of three flocks of 10 pigeons each. Every

bird's position, velocity and acceleration were sampled with time, and the

researchers used this data to determine which pigeons have a direct impact on

each individual in the group, constructing a causal network that can be used to

further observe the deep interaction rules.

They

determined a number of trends in flock motion. Depending on factors, like its

location in the flock, every pigeon has neighbors it influences as well as

neighbors it is influenced by. Additionally, the influencers are likely to

change throughout the flight.

They

determined a number of trends in flock motion. Depending on factors, like its

location in the flock, every pigeon has neighbors it influences as well as

neighbors it is influenced by. Additionally, the influencers are likely to

change throughout the flight.

"Interestingly,

the individuals closer to the mass center and the average velocity direction

are more influential to others, which means location and flight direction are

two factors that matter in their interactions," Chen said.

Though

pigeon social patterns were not considered, the researchers found flight

competition to be intensive, and previous work has shown flight hierarchies are

independent of pigeon dominance factors.

The

authors suggest their method is sufficiently general to study other coordinated

behaviors. Next, they plan to focus on the collective behaviors of immune

cells.