GBD

study could benefit from more environmental health and climate change

estimates

Recent

estimates in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study show that the combination

of air pollution, poor water sanitation and exposure to lead and radon is

responsible for 9 million premature deaths each year.

Recent

estimates in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study show that the combination

of air pollution, poor water sanitation and exposure to lead and radon is

responsible for 9 million premature deaths each year.

Yet

this figure captures only a fraction of the real burden of toxic pollutants in

the environment, and it doesn’t consider climate change, according to a

community of scientists led by researchers in the UW Department of

Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) in the School of

Public Health.

In a new paper,

researchers highlight key challenges that limit the scope and accuracy of

current GBD estimates for environmental health risk factors and propose

strategies to clarify the true environmental footprint on health from chemical

pollution and climate change.

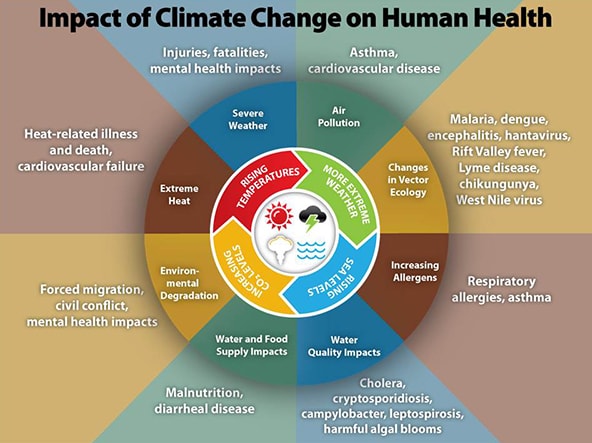

“There

are currently no GBD estimates related to a host of globally distributed toxic

pollutants or to climate change, which is arguably the greatest environmental

threat of them all,” said Dr. Howard Hu,

corresponding author and an affiliate professor in DEOHS.

Specifically,

climate change is not considered in a new type of GBD analysis, published in The Lancet in 2018, that forecasts

health and drivers of health on a global scale over the next 20 years.

One

reason for this is that climate change cannot easily be captured as a distinct

exposure, and there are unique data and modeling limitations, according to the

commentary. Additionally, “it is unclear what the baseline level for climate

risk should be, given its unique status as a constantly changing global

system,” the researchers wrote.

The

GBD—coordinated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

(IHME)—provides a tool to quantify health loss from hundreds of diseases,

injuries and risk factors to help provide an evidence base for decision-making.

The GBD incorporated a limited set of climate risks in its 2000 analysis but

has since opted not to include climate risk in recent reports.

The

new GBD-Pollution and Health Initiative

To

close the gap in estimates of environmental health-related disease burden,

including those attributed to climate change, Hu and others came together to

form the GBD-Pollution and Health Initiative (PHI). The initiative involves key

partners from UW, IHME, the University of Toronto and the National Institute

for Environmental Health Sciences.

It

is based in DEOHS and draws on expertise from around the world, including

George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health,

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, McGill University and New York

University.

“The

thinking behind the initiative is that many countries, especially those that

are low- or middle-income and are striving to meet the United Nations’

Sustainable Development Goals, have the opportunity to avoid some of the

environmental tragedies that have plagued high-income countries and to engage

in ‘smart’ development,” Hu said.

“To

do so, policymakers need to know the identity, magnitude and potential

consequences of the environmental risk factors specific to their country.”

A

research agenda proposed in the commentary stems from a 2018 GBD-PHI workshop.

According to Hu, a workshop orchestrator, current GBD estimates only count

environmental impacts from air pollution, lead, radon and select occupational

exposures.

What

is missing are estimates related to climate change and other pollutants “that

are highly toxic, globally distributed and arguably having significant impacts

on health or functioning,” such as mercury, arsenic, pesticides, phthalates and

polychlorinated biphenyls or PCBs.

Measurement

challenges

Another

challenge is that most GBD data come from high-income countries, which have

lower levels of pollution compared to low- and middle-income countries.

Also,

current GBD metrics rely on outcomes that meet diagnostic criteria, “an

approach that lacks the ability to fully capture critical sub-clinical effects

such as moderate reductions in IQ from neurotoxicants like lead or mercury,” Hu

said.

Such

impacts are only counted in the GBD if IQ loss results in intellectual

disability (IQ less than 85). However, modest reductions in IQ are well known

to have major impacts on a person’s capacity for learning and the amount of

money they may make in their lifetime, upstream factors that could influence

health.

Since

sub-clinical effects have major implications for individuals and society but

are not fully captured by GBD methods, the commentary suggests, as an

alternative, measuring these effects based on other metrics such as those for

human capital developed recently by IHME and the World Bank. This metric was

described in The Lancet in 2018.

Collaboration

could lead to new data and methods

The

GBD-PHI is looking to leverage existing research and stimulate collaborations

with environmental health scientists, particularly those who can address the

lack of data on exposures to pollutants in low- and middle-income countries.

“We

share the desire to more completely capture the burden associated with

environmental risk factors, and we have continued to add new environmental risk

factors and new risk-outcome pairs with each new iteration of the GBD study,”

said Jeffrey Stanaway,

assistant professor of health metrics sciences at IHME and a co-author of the

commentary.

Said

Rachel Shaffer, lead author of the commentary and a DEOHS doctoral student in

environmental toxicology: "The GBD is highly influential in the global

public health policy arena. It is crucial that environmental exposures are more

fully incorporated and considered in future iterations of the GBD so

governments and policymakers can make appropriate decisions to allocate

resources and improve the health of their populations."