URI scientist awarded $2.2 million grant to investigate

mouth bacteria

|

| Gingivitis (Wikipedia) |

His analogies help his students

at the University of Rhode Island understand what he calls the Microbiome

Revolution and all of the good and bad bacteria that live on and in the human

body. And his underlying message is clear: Poor oral health is one of the best

predictors of heart disease later in life.

“If you’re always having

gingivitis, or if you’ve had more than one periodontal infection, then your

risk for heart disease is really high,” said Ramsey, URI assistant professor of

cell and molecular biology. “And you’re much more likely to develop periodontal

infections or have heart disease if you have type 2 diabetes.”

“It’s an accessible community,”

he said. “I really want to understand who are the keystone organisms in the

mouth, who anchors the microbial community in there.”

To investigate the relationship

among oral bacteria, Ramsey has been awarded a five-year, $2.2 million grant by

the National Institutes of Health. He is collaborating on the project with

Jessica Mark Welch, associate scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in

Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and Jiyeon Kim, URI assistant professor of

chemistry. Three doctoral students and six undergraduates are also

participating in the research.

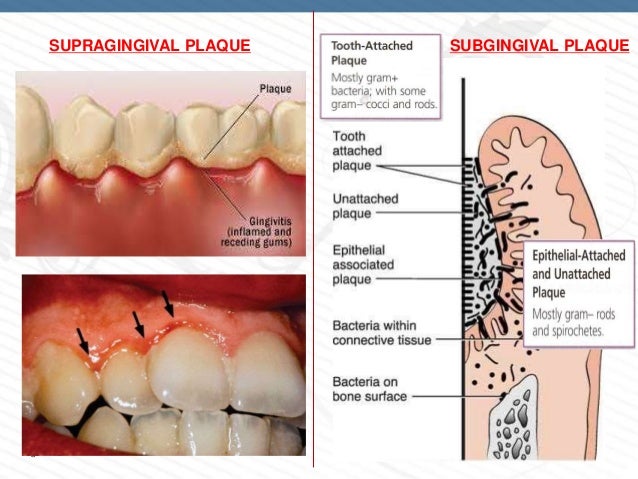

According to Ramsey, many oral

bacteria are dependent on multispecies interactions for their survival. So the

research team is investigating the relationship among the 20 to 30 most

encountered species of bacteria in a microbial community called the

supragingival plaque, which is located on the tooth surface just above the

gumline.

According to Ramsey, many oral

bacteria are dependent on multispecies interactions for their survival. So the

research team is investigating the relationship among the 20 to 30 most

encountered species of bacteria in a microbial community called the

supragingival plaque, which is located on the tooth surface just above the

gumline.

“In studying this plaque, we

want to see who’s interacting with who,” he said.

“If we see bacteria stuck to

each other, the probability of some meaningful interaction taking place is

incredibly high. So we’ll take those in the lab and grow them in isolation. If

I think one is dependent upon another, I can show that it grows terribly or not

at all by itself but when another species is present it grows great. But is it

a one-way interaction or is it mutually beneficial?”

Ramsey is most interested in

understanding the mechanisms responsible for the interactions and which

mechanisms promote a healthy community of bacteria assembling in the mouth. He

especially hopes to identify the mechanisms that lead to the expulsion of

invading pathogens.

“This is important because when

you don’t have your normal microbial community, you could end up with a

complete ecological shift,” he said. “It’s like after a forest fire. Does it

eventually go back to being a forest or does it shift to something else? In the

case of the human body, if another microbial community takes over, it might not

be the one you want.”

While Ramsey describes his

research as “basic science,” he said it plays a role in a wide variety of human

health applications.

“Because we’re all trying to

avoid using antibiotics, there’s a big push on to find probiotics that you can

feed yourself to keep your normal microbial population stable,” he said. “But

first we need to know what is the nature of our healthy microbiome, and what

interactions are keeping the community stable?

“People are already advocating

for oral probiotics without fully understanding what the native community is

doing,” Ramsey added. “What are native species doing to keep the bad ones

suppressed? Are they actively suppressing them? And how is the community staying

stable and in good abundance?”

At the end of the five-year

grant, he expects to know how the bacteria in the supragingival plaque maintain

a healthy community. And then he plans to investigate the bacterial

relationships elsewhere in the mouth.