Brains of

girls and boys are similar, producing equal math ability

Carnegie Mellon University

In 1992, Teen Talk Barbie was

released with the controversial voice fragment, "Math class is hard."

In 1992, Teen Talk Barbie was

released with the controversial voice fragment, "Math class is hard." While the toy's release met with public backlash, this underlying assumption persists, propagating the myth that women do not thrive in science, technology, engineering and mathematic (STEM) fields due to biological deficiencies in math aptitude.

Jessica Cantlon at Carnegie Mellon University led a research team that comprehensively examined the brain development of young boys and girls.

Their research shows no gender difference in brain function or math ability. The results of this research are available online in the November 8 issue of the journal Science of Learning.

"Science doesn't align with

folk beliefs," said Cantlon, the Ronald J. and Mary Ann Zdrojkowski

Professor of Developmental Neuroscience at CMU's Dietrich College of Humanities

and Social Sciences and senior author on the paper.

"We see that children's brains function similarly regardless of their gender so hopefully we can recalibrate expectations of what children can achieve in mathematics."

"We see that children's brains function similarly regardless of their gender so hopefully we can recalibrate expectations of what children can achieve in mathematics."

Cantlon and her team conducted the

first neuroimaging study to evaluate biological gender differences in math

aptitude of young children.

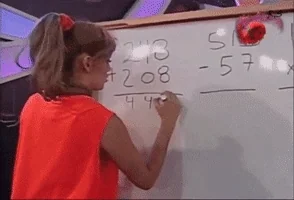

Her team used functional MRI to

measure the brain activity in 104 young children (3- to 10-years-old; 55 girls)

while watching an educational video covering early math topics, like counting

and addition. The researchers compared scans from the boys and girls to

evaluate brain similarity.

In addition, the team examined brain maturity by comparing the children's scans to those taken from a group of adults (63 adults; 25 women) who watched the same math videos.

In addition, the team examined brain maturity by comparing the children's scans to those taken from a group of adults (63 adults; 25 women) who watched the same math videos.

After numerous statistical comparisons, Cantlon and her team found no difference in the brain development of girls and boys. In addition, the researchers found no difference in how boys and girls processed math skills and were equally engaged while watching the educational videos.

Finally, boys' and girls' brain maturity were statistically equivalent when compared to either men or women in the adult group.

"It's not just that boys and

girls are using the math network in the same ways but that similarities were

evident across the entire brain," said Alyssa Kersey, postdoctoral scholar

at the Department of Psychology, University of Chicago and first author on the

paper.

"This is an important reminder that humans are more similar to each other than we are different."

"This is an important reminder that humans are more similar to each other than we are different."

The researchers also compared the

results of the Test of Early Mathematics Ability, a standardized test for 3- to

8-year-old children, from 97 participants (50 girls) to gauge the rate of math

development.

They found that math ability was equivalent among the children and did not show a difference in gender or with age. Nor did the team find a gender difference between math ability and brain maturity.

They found that math ability was equivalent among the children and did not show a difference in gender or with age. Nor did the team find a gender difference between math ability and brain maturity.

This study builds on the team's

previous work that found equivalent behavioral performance on a range of

mathematics tests between young boys and girls.

Cantlon said she thinks society and

culture likely are steering girls and young women away from math and STEM

fields. Previous studies show that families spend more time with young boys in

play that involves spatial cognition.

Many teachers also preferentially spend more time with boys during math class, predicting later math achievement. Finally, children often pick up on cues from their parent's expectations for math abilities.

Many teachers also preferentially spend more time with boys during math class, predicting later math achievement. Finally, children often pick up on cues from their parent's expectations for math abilities.

"Typical socialization can

exacerbate small differences between boys and girls that can snowball into how

we treat them in science and math," Cantlon said. "We need to be

cognizant of these origins to ensure we aren't the ones causing the gender

inequities."

This project is focused on early

childhood development using a limited set of math tasks. Cantlon wants to

continue this work using a broader array of math skills, such as spatial

processing and memory, and follow the children over many years.

Cantlon and Kersey were joined by

Kelsey Csumitta at the University of Rochester on the study, titled

"Gender Similarities in the Brain during Mathematics Development."

This research received funding from the National Science Foundation and the

National Institutes of Health.