By GRACE KELLY/ecoRI News staff

Salting roads as a method of preventing ice from forming began eight decades ago. (Grace Kelly/ecoRI News)

Winter is here, and with it the tried and true method for keeping roads from becoming slippery: salt.

Salting roads as a method of preventing ice from forming began in 1938 in New Hampshire and has become the go-to method for safe winter driving. It’s effective. According to a 1992 study from Marquette University, salting the roads reduced winter car accidents by 87 percent.

While it’s an effective method for safer winter driving, throwing

tons of salt down comes with side effects. When cavalries of trucks start to

season the roads, they also inadvertently contaminate freshwater wetlands.

“Road salt can travel up to 170 meters [558 feet] from the road

across the landscape into wetlands like vernal pools,” said Nancy Karraker, an

associate professor of wetland ecology and herpetology at the University of

Rhode Island.

Karraker has been studying the impacts of road salt on vernal pools and freshwater wetlands for years and has concerns about salt’s effects on the invertebrates that make fresh water their home.

“Through experiments, I found that wood frogs’ eggs and their

tadpoles were only affected at the highest salinity concentration, so they were

a little bit more resilient,” she said.

“But with the spotted salamanders, there was a significant decline in survival of both eggs and tadpoles with the average concentration of salt we were seeing at vernal pools near roads.”

“But with the spotted salamanders, there was a significant decline in survival of both eggs and tadpoles with the average concentration of salt we were seeing at vernal pools near roads.”

And getting an average, or even high, concentration of salt in the

water is easier to do than you might think.

“If you think about the head of a penny, if you cover half of the

head of that penny with rock salt, dump that into a quart of water and stir it

until it dissolves, that’s the salt concentration that is harmful to spotted

salamanders,” Karraker said.

“And if you completely cover the head of a penny and let a little bit spill over the side, and dump that in a quart of water, that’s the amount that harms wood frogs. So it’s a tiny amount of salt, it’s a very low concentration that impacts these animals.”

“And if you completely cover the head of a penny and let a little bit spill over the side, and dump that in a quart of water, that’s the amount that harms wood frogs. So it’s a tiny amount of salt, it’s a very low concentration that impacts these animals.”

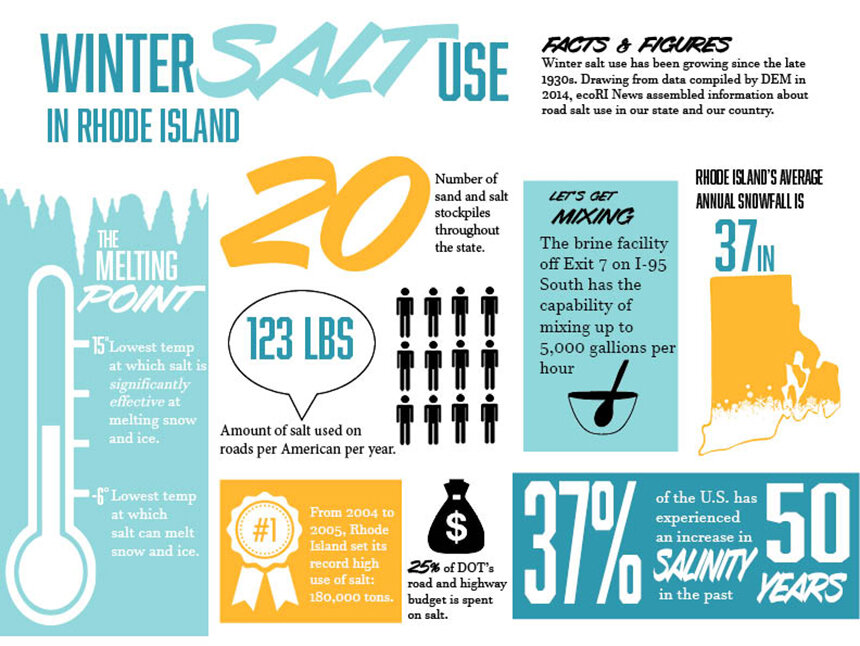

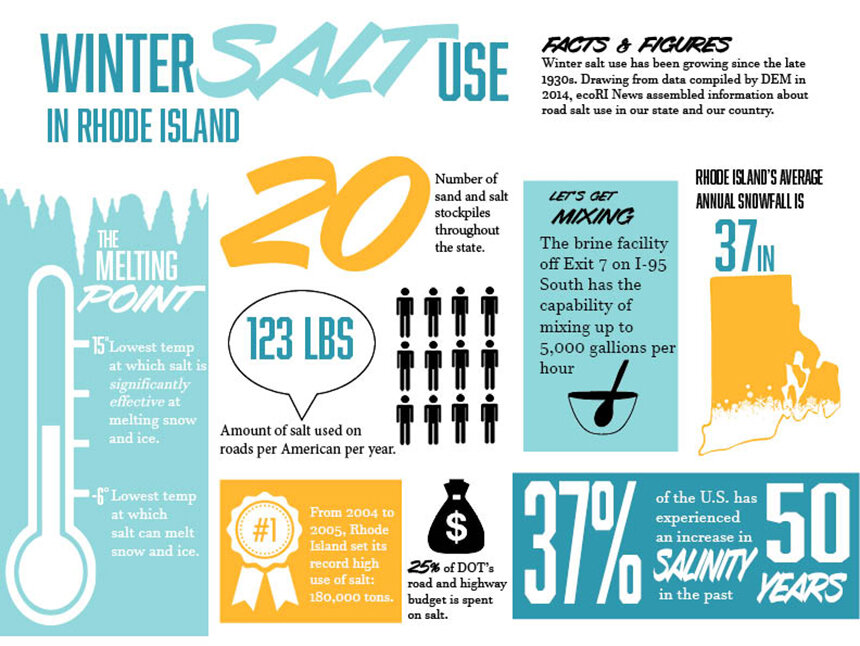

Rhode Island doesn’t just use a pinch of salt to season its roads.

From 2005 to 2013, Rhode Island roads received an average of 516 pounds of salt

per lane mile annually, according to a 2014 report by the Rhode Island Department of

Administration’s Division of Planning.

Nationwide, an estimated 10 million to 20 million

tons of salt is dumped on roads annually — about 120 pounds for

every American. Though many states, including Rhode Island, are turning to

brine — a mixture of water and salt — instead of chunky crystals, for Karraker

a salt by any other name still tastes as salty.

“A salt is a salt is a salt — it doesn’t matter if you’re talking

about sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, potassium chloride, and brining just

means that you’ve got a salt solution that’s been diluted a bit with water so

you can spray it on the road so it acts more quickly to limit ice buildup.”

Karraker hopes that the state departments of environmental

management and transportation will consider having “no salt” designations for

roads that are near freshwater wetlands.

“You see these signs that say, ‘low road salt use’ near public

drinking water sources and I wish they would do the same for biodiversity,” she

said.

“Why couldn’t we designate certain roads around our wildlife management areas as low road salt use areas to protect biodiversity? Why can’t we start to think about protecting biodiversity like we think about protecting our drinking water? I think it’s important.”

“Why couldn’t we designate certain roads around our wildlife management areas as low road salt use areas to protect biodiversity? Why can’t we start to think about protecting biodiversity like we think about protecting our drinking water? I think it’s important.”