Statewide

autism study finds later diagnoses for girls, high rates of co-occurring

disorders

By Kerry

Benson

A new study analyzing the first 1,000 participants in the Rhode Island Consortium for Autism Research and Treatment (RI-CART) identifies key trends in the presentation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. The study was published in Autism Research on Monday, Jan. 20.

The

first finding was that girls with autism receive a diagnosis, on average,

nearly 1.5 years later than boys. This is likely because parents and clinicians

tend to notice language delays as the first sign of autism, and girls in the

study exhibited more advanced language abilities compared to boys, said study

authors Stephen Sheinkopf and Dr. Eric Morrow.

Autism

is far more common in boys. The RI-CART study found more than four times as

many boys as girls with autism; however, given the large size of the sample,

the study was well-powered to evaluate girls with autism.

The finding that girls with autism are diagnosed later is clinically important, said Morrow, an associate professor of molecular biology, neuroscience and psychiatry at Brown University.

The finding that girls with autism are diagnosed later is clinically important, said Morrow, an associate professor of molecular biology, neuroscience and psychiatry at Brown University.

“The major treatment that has some efficacy in autism is early diagnosis and getting the children into intensive services, including behavioral therapy,” Morrow said. “So if we’re identifying girls later, that may delay their treatments.”

Sheinkopf,

an associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Brown, emphasized the

importance of early recognition.

“We

need to think about how we can improve recognition of autism in individuals —

including many of these girls — who don’t have the same level of primary

language delay but may have other difficulties in social communication, social

play and adapting to the social world,” he said.

“And as we improve diagnosis for the full range of individuals in the early years, we must also rethink early interventions to make sure they’re designed appropriately for children who might need assistance on more nuanced elements of social adaptation. We need to refine treatments so they cater to individual needs.”

“And as we improve diagnosis for the full range of individuals in the early years, we must also rethink early interventions to make sure they’re designed appropriately for children who might need assistance on more nuanced elements of social adaptation. We need to refine treatments so they cater to individual needs.”

Based

at Bradley Hospital in East Providence, the team behind RI-CART represents a

public-private-academic collaborative — a partnership between researchers at

Brown, Bradley Hospital and Women and Infants —

that also involves nearly every site of service for families affected by autism

in Rhode Island.

The study team also integrated members of the autism community, family members and particularly the Autism Project, a family support service for autism in the state.

The study team also integrated members of the autism community, family members and particularly the Autism Project, a family support service for autism in the state.

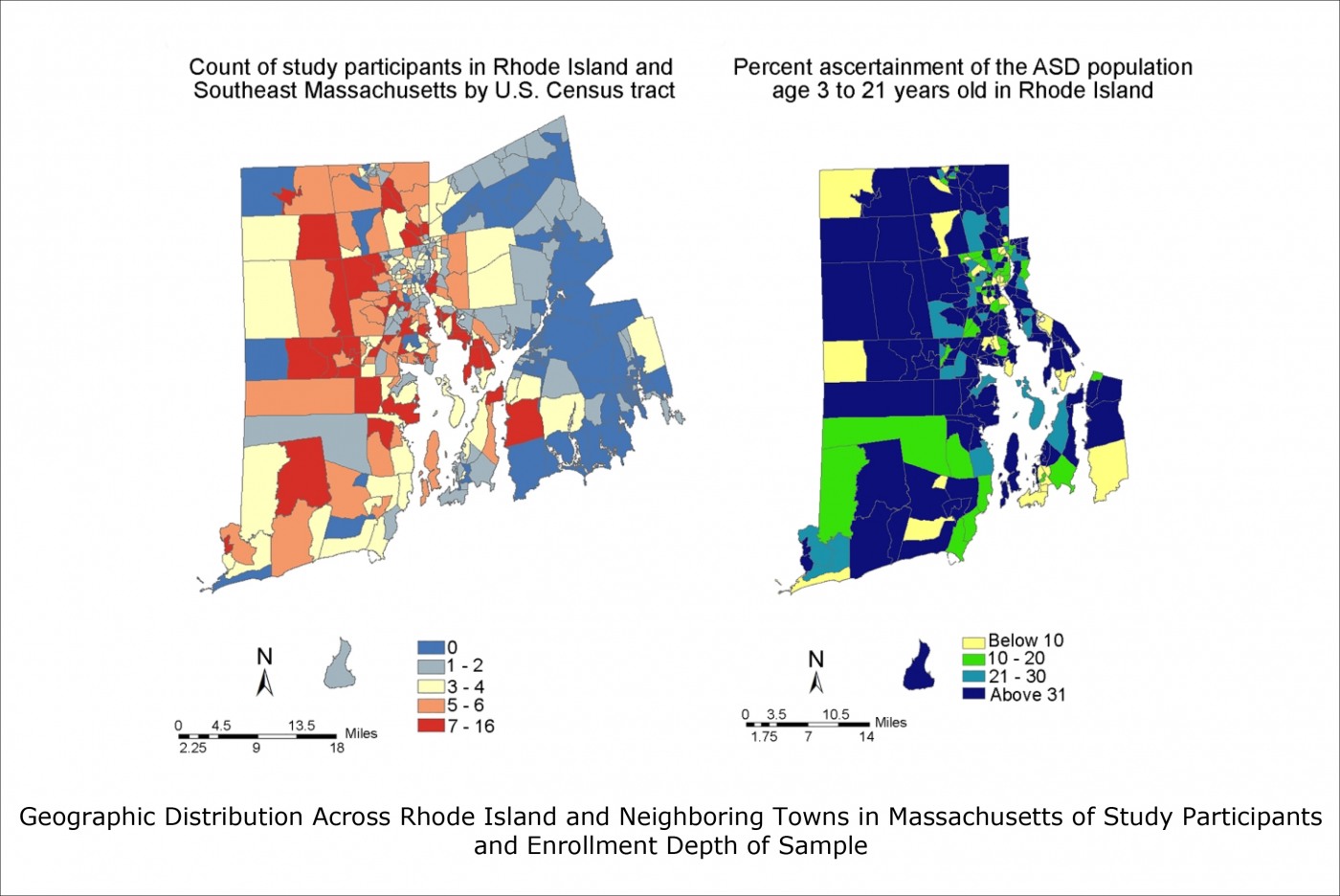

By

engaging both the community and treatment providers, the study enrolled more

than 20 percent of pediatric-age individuals with autism in Rhode Island.

Participants were recruited from all geographic regions of the state, and as

part of the study, they were given rigorous in-person assessments.

Most

participants had received an autism diagnosis prior to entering the study (a

community diagnosis), and their diagnosis was subsequently confirmed by an

in-person assessor, meaning that they also received a research diagnosis. The

study also included individuals whose diagnoses were less clear cut.

For example, some individuals received either a community diagnosis or a research diagnosis, but not both. Other individuals were referred to the study but did not have evidence of autism from either a community evaluation or the research assessment.

For example, some individuals received either a community diagnosis or a research diagnosis, but not both. Other individuals were referred to the study but did not have evidence of autism from either a community evaluation or the research assessment.

“The

group that was diagnostically less clear-cut represents the complexity that

clinicians encounter on a daily basis, so it’s a realistic sample in that

sense,” Sheinkopf said. “This full range of heterogeneous autism presentation

is rather unique to our study.”

The

other major finding of the study was that people with autism frequently exhibit

co-occurring psychiatric and medical conditions.

Nearly

half of the participants reported another neurodevelopmental disorder (i.e.,

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or intellectual disability),

while 44.1 percent reported a psychiatric disorder, 42.7 percent reported a

neurological condition (i.e., seizures/epilepsy, migraines, tics), 92.5 percent

reported at least one general medical condition and nearly a third reported

other behavioral problems.

“These co-occurring conditions need also to be a focus of treatment for patients,” Morrow said.

“Many people with autism need support for the psychiatric and emotional challenges that are prevalent in people who share this one diagnosis,” Sheinkopf added. “These are clinically complicated individuals who deserve strong, sophisticated, multidimensional, multidisciplinary care.”

Sheinkopf and Morrow say they’re encouraged by the support and collaboration of a variety of health care providers, community members and particularly, by the level of commitment shown by the families who participated in the study.

Going forward, they’re hopeful that the RI-CART registry will lead to more studies that will improve the lives of people with autism and their families, particularly because the cohort currently involves such a wide age range of participants, including individuals with autism ages 2 to nearly 64.

“Given

that autism is a developmental disorder, the field really needs to focus on

longitudinal studies: following people’s development and transitions,” Morrow

said. “I think we’re going to learn even more when we follow children from a

very young age as they develop, including into adulthood.”

The

study was funded by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (286756),

the Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation

Institute at Brown University, the National Institutes of

Health (though the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences), the

Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (KL2 TR002530 and ULI TR002529) and

the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH101076 and T32 MH019927).

RI-CART

received pilot support from the Carney Institute for Brain Science at Brown,

the Norman Prince Neuroscience Institute and the Department of Psychiatry and

Human Behavior.