The

Species We Lost in 2019

|

| George, the last Achatinella apexfulva. Photo: David Sischo /Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources |

The year started with the extinction of a tiny Hawaiian snail and ended with the loss of one of the world’s largest freshwater fishes.

Along the way we also said goodbye to three bird species, a shark, two frogs, several plants, and a whole lot more.

About two dozen species were declared extinct (or nearly so) in 2019, although the total number of species lost this year probably numbers in the thousands.

Scientists typically wait years or even decades before declaring a species well and truly extinct, and even then only after conducting extensive searches.

Of course, you can only count what you know exists. Most extinctions, sadly, occur among species that have never been officially observed or named. These plants and animals often live in extremely narrow habitats, making them particularly vulnerable to habitat destruction, pollution, extreme weather events, invasive species or other threats.

That doesn’t mean they’ll never be identified — several recently reported extinctions represent species that were discovered among museum samples long after the plants or animals were gone — but you can’t save what you don’t know needs saving in the first place.

Although it may take some time to truly understand this year’s effect on the world’s biodiversity, here are the species that scientists and the conservation community declared lost during 2019, culled from the IUCN Red List, scientific publications, a handful of media articles and my own reporting.

Only one of these extinctions was observed in real time, when an endling (the last of its kind) died in public view. Most haven’t been seen in decades and were finally added to the list of extinct species.

A few represent local extinctions where a species has disappeared from a major part of its range, an important thing to watch since habitat loss and fragmentation are often the first steps toward a species vanishing.

Finally, some of these extinctions are tentative, with scientists still looking for the species — an indication that hope remains.

Achatinella apexfulva — The last individual of this Hawaiian tree snail, known as “Lonesome George,” died in captivity on New Year’s Day. Disease and invasive predators drove it to extinction. This tiny creature’s disappearance probably generated the most media attention of any lost species in 2019.

|

| A related speckled skink species. Photo: Marieke Lettink, used with permission. |

Boulenger’s speckled skink (Oligosoma infrapunctatum) — A “complete enigma,” unseen for more than 130 years. Scientists hope the announcement of its possible extinction will jumpstart efforts to relocate it and conserve its endangered relatives.

|

| The extinct Bramble Cay melomys. Photo: Photo: State of Queensland, Environmental Protection Agency (uncredited) |

Catarina pupfish (Megupsilon aporus) — This Mexican freshwater fish was known from one spring, which was destroyed by groundwater extraction. The fish was last seen in the wild in 1994, and the last captive population died out in 2012.

Chinese paddlefish (Psephurus gladius) — One of the world’s largest freshwater fish, native to the Yangtze River, the paddlefish probably died out between 2005 and 2010 due to overfishing and habitat fragmentation. The IUCN still lists it as “critically endangered,” but a paper published Dec. 23, 2019, declared it extinct after several surveys failed to locate the species.

Corquin robber frog (Craugastor anciano) — Last seen in 1990. Native to two sites in Honduras, it was probably killed off by habitat loss and the chytrid fungus.

Cryptic treehunter (Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti) — A Brazilian bird species last seen alive in 2007 — seven years before scientists officially described it. Its forest habitat has been extensively logged and converted to agriculture.

Cunning silverside (Atherinella callida) — This Mexican freshwater fish hasn’t been seen since 1957. The IUCN declared it extinct in 2019.

Etlingera heyneana — A plant species collected just one time in 1921 near Jakarta, on Java, the world’s most populous island. The IUCN listed it as extinct in 2019, noting that “practically all natural land in Jakarta has been developed.”

Fissidens microstictus — This Portuguese plant species lived in what is now a highly urbanized area and was last seen in 1982. (Scientists declared it extinct back in 1992, but the IUCN didn’t list it as such until this year.)

|

| 2007 photo of a tiger rescued from poachers in Laos. Photo: Reed Kennedy (CC BY-SA 2.0) |

Indochinese tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) in Laos — A local extinction (known as an extirpation) and a major loss for this big cat.

Lake Oku puddle frog (Phrynobatrachus njiomock) — Known from one location in Cameroon and unseen since 2010, the IUCN this year declared the recently discovered species “critically endangered (possibly extinct).”

|

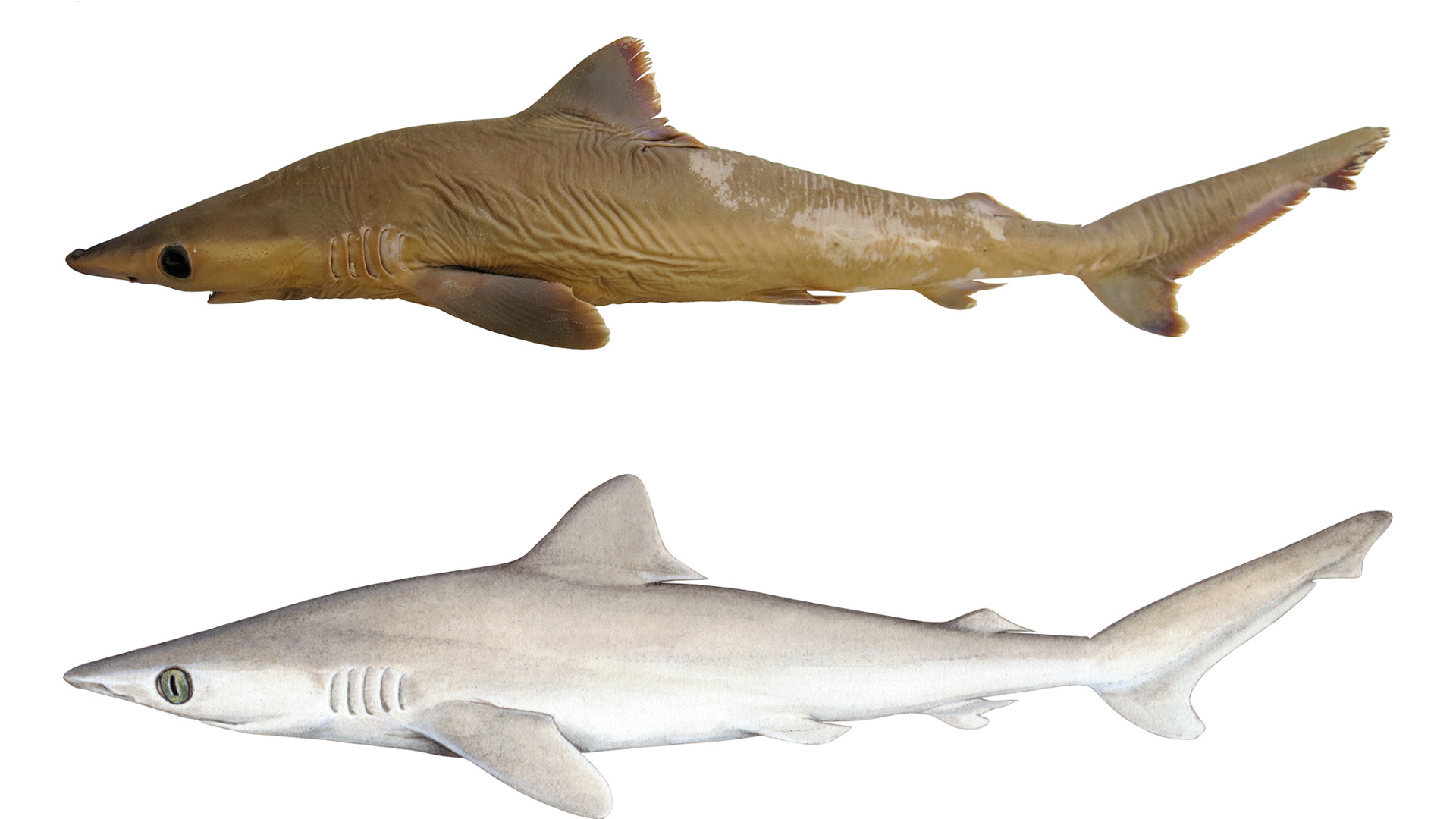

“Lost shark.” Photo: PLOS One

|

“Lost shark” (Carcharhinus obsolerus) — Described from museum samples in 2019, the species hasn’t been seen since the 1930s. It was probably wiped out by overfishing.

|

| The related and endangered Zanzibar red colobus (Piliocolobus kirkii). Photo by Marc Veraart (CC BY 2.0) |

Nobregaea latinervis — A moss species last seen in Portugal in 1946 and declared extinct in 2019 (based on a 2014 survey).

Poo-uli (Melamprosops phaeosoma) — Invasive species and diseases wiped out this Hawaiian bird, which was last seen in 2004 and declared extinct in 2019.

|

| Poo-uli © Paul E. Baker, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Public Domain) |

Sierra de Omoa streamside frog (Craugastor omoaensis) — Another frog from Honduras. Unseen since 1974, it was probably a victim of habitat loss and the chytrid fungus.

Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) in Malaysia — Another extirpation, although the species still exists (on tenuous footing) in Indonesia.

Vachellia bolei — A rare legume tree possibly driven extinct by sand mining and other habitat destruction.

|

| A related species of grassland dragon, photographed in 1991 by John Wombey/CSIRO (CC BY 3.0) |

Villa Lopez pupfish (Cyprinodon ceciliae) — This Mexican fish’s only habitat, a 2-acre spring system, dried up in 1991 and it hasn’t been seen since. The IUCN declared it extinct in 2019.

|

| Photo: Emily King, courtesy Turtle Survival Alliance |

In addition to these extinctions, the IUCN last year declared several species “extinct in the wild,” meaning they now only exist in captivity.

They include the Spix’s Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii), Ameca shiner (Notropis amecae), banded allotoca (Allotoca goslinei), marbled swordtail (Xiphophorus meyeri), Charo Palma pupfish (Cyprinodon veronicae), kunimasu (Oncorhynchus kawamurae) and Monterrey platyfish (Xiphophorus couchianus).

What will the future hold for these and other lost species? Some could be rediscovered (the Miss Waldron’s red colobus seems the most likely candidate), but the rest should serve as a stark reminder of what we’re losing all around us every day — and a clarion call to save what’s left.

Main image photo credits: Alagoas Foliage-gleaner © Ciro Albano, courtesy IUCN. Poo-uli © Paul E. Baker, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Public Domain). A relative of the Victorian grasslands earless dragon, photographed in 1991 by John Wombey/CSIRO (CC BY 3.0). Bramble Cay melomys via State of Queensland, Environmental Protection Agency (uncredited).

John R. Platt is the editor of The Revelator. An award-winning environmental journalist, his work has appeared in Scientific American, Audubon, Motherboard, and numerous other magazines and publications. His “Extinction Countdown” column has run continuously since 2004 and has covered news and science related to more than 1,000 endangered species.

He is a member of the Society of Environmental Journalists and the National Association of Science Writers. John lives on the outskirts of Portland, Ore., where he finds himself surrounded by animals and cartoonists. http://twitter.com/johnrplatthttp://johnrplatt.com https://www.instagram.com/johnrplatt