Jeffrey Fields, University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

|

| Benny Marty/Shutterstock.com |

Relations between the United States and Iran have been fraught for decades – at least since the U.S. helped overthrow a democracy-minded prime minister, Mohammed Mossadegh, in August 1953.

The U.S. then supported the long, repressive reign of the shah of Iran, whose security services brutalized Iranian citizens for decades.

The two countries have been particularly hostile to each other since Iranian students took over the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in November 1979, resulting in, among other consequences, economic sanctions and the severing of formal diplomatic relations between the nations.

Since 1984, the U.S. State Department has listed Iran as a “state sponsor of terrorism,” alleging the Iranian government provides terrorists with training, money and weapons.

Some of the major events in U.S.-Iran relations highlight the differences between the nations’ views, but others arguably presented real opportunities for reconciliation.

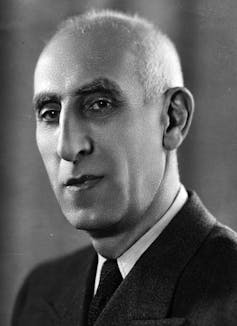

1953: US overthows Mossadegh

|

| Mohammed Mossadegh. Wikimedia Commons |

The U.S. feared disruption in the global oil supply and worried about Iran falling prey to Soviet influence. The British feared the loss of cheap Iranian oil.

Unable to settle the dispute, President Dwight Eisenhower decided it was best for the U.S. and the U.K. to get rid of Mossadegh.

Operation Ajax, a joint CIA-British operation, convinced the shah of Iran, the country’s monarch, to dismiss Mossadegh and drive him from office by force.

Mossadegh was replaced by a much more Western-friendly prime minister, hand-picked by the CIA.

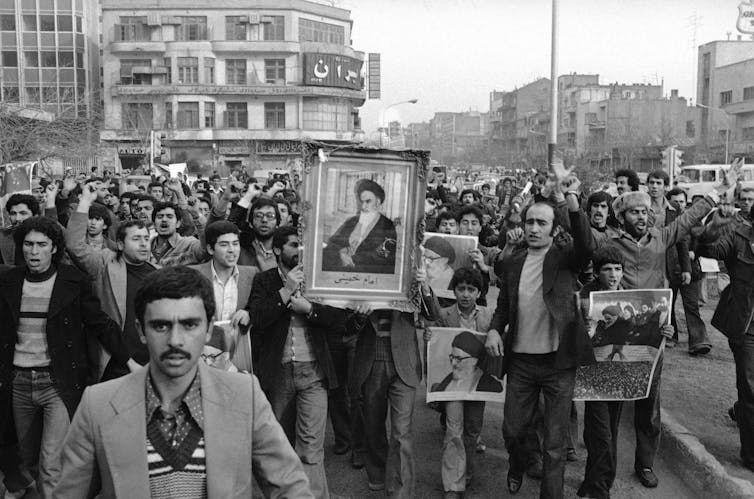

1979: Revolutionaries oust the shah, take hostages

|

| Demonstrators in Tehran demand the establishment of an Islamic Republic. AP Photo/Saris |

Pahlavi enriched himself and used American aid to fund the military while many Iranians lived in poverty.

Dissent was often violently quashed by SAVAK, the shah’s security service.

In January 1979, the shah left Iran, ostensibly to seek cancer treatment.

Two weeks later, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile in Iraq and led a drive to abolish the monarchy and proclaim an Islamic government.

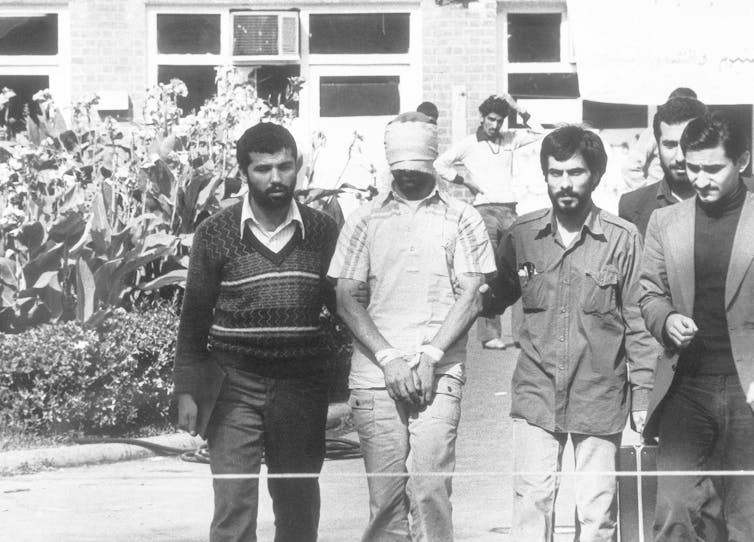

|

| Iranian students at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran show a blindfolded American hostage to the crowd in November 1979. AP Photo, File |

Outraged Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on Nov. 4, taking 52 Americans hostage.

That convinced Carter to sever U.S. diplomatic relations with Iran on April 7, 1980.

Two weeks later, the U.S. military launched a mission to rescue the hostages, but it failed, with aircraft crashes in the Iranian desert killing eight U.S. servicemembers.

The shah died in Egypt in July 1980, but the hostages weren’t released until Jan. 20, 1981, after 444 days of captivity.

1980-1988: US tacitly sides with Iraq

|

| An Iranian cleric, left, and an Iranian soldier wear gas masks to protect themselves against Iraqi chemical-weapons attacks in May 1988. Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images |

In September 1980, Iraq invaded Iran, an escalation of the two countries’ regional rivalry and religious differences: Iraq was governed by Sunni Muslims but had a Shia Muslim majority population; Iran was led and populated mostly by Shiites.

The U.S. was concerned that the conflict would limit the flow of Middle Eastern oil and wanted to ensure the conflict didn’t affect its close ally, Saudi Arabia.

The U.S. supported Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in his fight against the anti-American Iranian regime.

As a result, the U.S. mostly turned a blind eye toward Iraq’s “almost daily” use of chemical weapons against Iran.

U.S. officials moderated their usual opposition to those illegal and inhumane weapons because the U.S. State Department did not “wish to play into Iran’s hands by fueling its propaganda against Iraq.”

In 1988, the war ended in a stalemate, with a combined total of more than 500,000 military deaths and 100,000 civilians dead on both sides.

1981-1986: US secretly sells weapons to Iran

|

| Lt. Col. Oliver North is sworn in to testify before Congress about a U.S. deal to sell weapons to Iran, in breach of an embargo, and use the money to support rebels in Nicaragua. AP Photo/Lana Harris |

That left the Iranian military, in the middle of its war with Iraq, desperate for weapons and aircraft and vehicle parts to keep fighting.

The Reagan administration decided that the embargo would likely push Iran to seek support from the Soviet Union, the U.S.‘s rival in the Cold War.

Rather than formally ending the embargo, U.S. officials agreed to secretly sell weapons to Iran starting in 1981.

Later, the transactions were justified as incentives to help Iran persuade militants to release U.S. hostages being held in Lebanon.

The last shipment, of anti-tank missiles, was in October 1986. In November of that year, a Lebanese magazine exposed the deal.

That revelation sparked the Iran-Contra scandal in the U.S., in which Reagan’s officials were found to have collected money from Iran for the weapons, and illegally sent those funds to anti-socialist rebels – the Contras – in Nicaragua.

1988: US Navy shoots down Iran Air flight 655

|

| At a mass funeral for 76 of the 290 people killed in the shootdown of Iran Air 655, mourners hold up a sign depicting the incident. AP Photo/CP/Mohammad Sayyad |

Either during or just after that exchange of gunfire, the Vincennes crew mistook a passing civilian Airbus passenger jet for an Iranian F-14 fighter.

They shot it down, killing all 290 people aboard.

The U.S. called it a “tragic and regrettable accident,” but Iran believed the plane’s downing was intentional.

In 1996, the U.S. agreed to pay US$131.8 million in compensation to Iran.

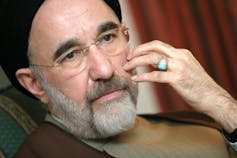

1997-1998: The US seeks contact

|

| Iranian President Mohammad Khatami. Prometheus72/Shutterstock.com |

U.S. President Bill Clinton sensed an opportunity for improved relations between the two countries.

He sent a message to Tehran through the Swiss ambassador there, proposing direct government-to-government talks.

Shortly thereafter, in early January 1998, Khatami gave an interview to CNN in which he expressed “respect for the great American people,” denounced terrorism and recommended an “exchange of professors, writers, scholars, artists, journalists and tourists” between the United States and Iran.

However, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei didn’t agree, so not much came of the mutual overtures as Clinton’s time in office came to an end.

|

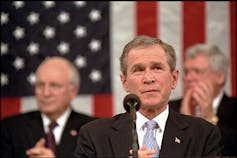

| President George W. Bush delivers the 2002 State of the Union address. Eric Draper/White House/Wikimedia Commons |

In 2000, U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright spoke to the U.S.-based American-Iranian Council and acknowledged the government’s role in the 1953 ouster of Mossadegh, but punctuated her remarks with criticism of Iranian domestic politics.

In his 2002 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush characterized Iran, Iraq and North Korea as constituting an “Axis of Evil” supporting terrorism and pursuing weapons of mass destruction, straining relations even further.

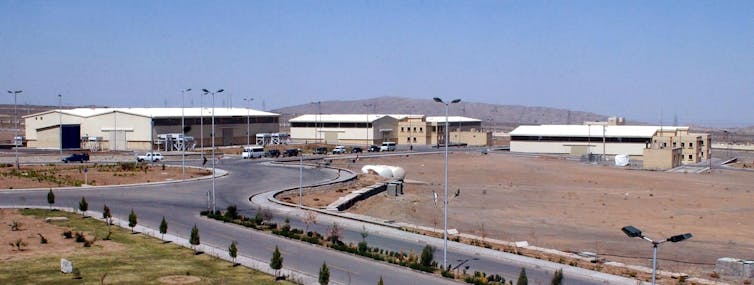

2002: Iran’s nuclear program raises alarm

|

| Inside these buildings at the Natanz nuclear facility in Iran, technicians enrich uranium. AP Photo/Vahid Salemi |

In August 2002, an exiled rebel group announced that Iran had been secretly working on nuclear weapons at two installations that had not previously been publicly revealed.

That was a violation of the terms of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, which Iran had signed, requiring countries to disclose their nuclear-related facilities to international inspectors.

One of those formerly secret locations, Natanz, housed centrifuges for enriching uranium, which could be used in civilian nuclear reactors or enriched further for weapons.

Starting in roughly 2005, U.S. and Israeli government cyberattackers together reportedly targeted the Natanz centrifuges with a custom-made piece of malicious software that became known as Stuxnet.

That effort, which slowed down Iran’s nuclear program was one of many U.S. and international attempts – mostly unsuccessful in the long term – to curtail Iran’s progress toward building a nuclear bomb.

2003: Iran writes to Bush administration

In May 2003, senior Iranian officials quietly contacted the State Department through the Swiss embassy in Iran, seeking “a dialogue 'in mutual respect,’” addressing four big issues: nuclear weapons, terrorism, Palestinian resistance and stability in Iraq.

Hardliners in the Bush administration weren’t interested in any major reconciliation, though Secretary of State Colin Powell favored dialogue and other officials had met with Iran about al-Qaida.

When Iranian hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president of Iran in 2005, the opportunity died. The following year, Ahmadinejad made his own overture to Washington in an 18-page letter to President Bush.

The letter was widely dismissed; a senior State Department official told me in profane terms that it amounted to nothing.

2015: Iran nuclear deal signed

|

| Representatives of several nations met in Vienna in July 2015 to finalize the Iran nuclear deal. Austrian Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs/Flickr |

Two years of secret, direct negotiations initially bilaterally between the U.S. and Iran and later with other nuclear powers culminated in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, commonly referred to as the Iran nuclear deal.

The deal was signed by Iran, the U.S., China, France, Germany, Russia and the United Kingdom in 2015. It severely limited Iran’s capacity to enrich uranium and mandated that international inspectors monitor and enforce Iran’s compliance with the agreement.

In return, Iran was granted relief from international and U.S. economic sanctions.

Though the inspectors regularly certified that Iran was abiding by the agreement’s terms, in May 2018 Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the agreement.

2020: US drones kill Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani

|

| An official photo from the Iranian government shows Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, killed in a Jan. 3 drone strike ordered by Trump. Iranian Supreme Leader Press Office/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images |

Soleimani is described by analysts as the second most powerful man in Iran after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei.

At the time, the Trump administration asserted that he was directing an imminent attack against U.S. assets in the region, but officials have not provided clear evidence to support that claim.

Iran responded by launching ballistic missiles that hit two American bases in Iraq. As Iran entered a heightened state of alert, preparing for a possible U.S. retaliation, it accidentally shot down a commercial Ukrainian airliner departing Tehran for Kyiv, killing all 176 people aboard.

[ Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter. ]

Jeffrey Fields, Associate Professor of the Practice of International Relations, University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.