Laurel Leff, Northeastern University

During the Nazi era, roughly 300,000 additional Jewish refugees could have gained entry to the U.S. without exceeding the nation’s existing quotas.

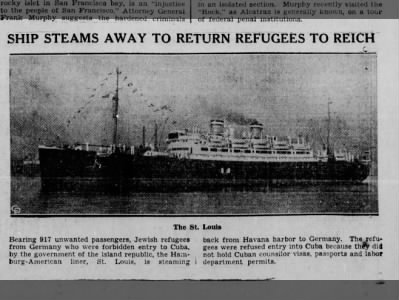

During the Nazi era, roughly 300,000 additional Jewish refugees could have gained entry to the U.S. without exceeding the nation’s existing quotas. The primary mechanism that kept them out: the immigration law’s “likely to become a public charge” clause. Consular officials with the authority to issue visas denied them to everyone they deemed incapable of supporting themselves in the U.S.

It is not possible to say what happened to these refugees. Some immigrated to other countries that remained outside Germany’s grip, such as Great Britain.

But many – perhaps most – were forced into hiding, imprisoned in concentration camps and ghettos, and deported to extermination centers.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/64772453/GettyImages_1156698653.0.jpg) |

| Trump meets with representatives of refugee groups who beg Trump for compassion. His face says it all. Vox.com. |

In August, the Trump administration resurrected the “the public charge” clause as a way to limit legal immigration without changing the immigration laws. The rules would deny admission to those unable to prove under tough new standards that they won’t claim government benefits.

A lower court had blocked that new rule with a preliminary injunction, but the Supreme Court lifted the injunction on January 27. The court’s decision allows the rules to go into effect everywhere, except Illinois.

Neither the five conservative justices in the majority, nor the four more liberal justices in dissent, explained their reasoning.

The many different organizations and states who have challenged the rules can continue their litigation, but the odds of ultimately winning aren’t good. Solicitor General Noel J. Francisco, who asked the Court to lift the stay, argued that the new rule was a reasonable interpretation of the statute that denies admission to anyone who is “likely at any time to become a public charge.”

As someone who has studied European Jews’ attempts to escape Nazi persecution and immigrate to the U.S., the administration’s evocation of the public charge clause is chilling.

Preventing 1930s immigration

|

| Jewish refugee from Vienna, Austria, upon arrival in Great Britain in 1938. Wikimedia Commons |

For the first five decades, the public charge provision barred few people, basically only those unable to work due to physical or mental handicaps.

After the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing Great Depression, the Hoover administration sought to combat unemployment by reducing the number of immigrants. But it didn’t want to change the recently implemented Immigration Act of 1924 that set annual overall and country-by-country quotas.

In September 1930, the State Department issued a press release that told consular officials that they “must refuse the visa,” to anyone they believed “may probably be a public charge at any time.”

The instructions achieved the desired effect. Within five months, only 10% of the quota slots allotted to European immigrants had been filled.

When the Roosevelt administration assumed power in March 1933, it continued the new interpretation of the public charge clause.

As refugees from first Germany and then most of Europe sought to escape Nazi persecution, the State Department used the public charge clause to limit the number of foreigners, most of whom were Jews, from immigrating to the U.S.

With anti-foreigners pushing for legislation decreasing the quotas and refugee advocates trying to hold the line, the out-of-the-spotlight approach had political appeal.

A State Department official acknowledged during hearings on a bill to cut the quotas 90% that “the administrative regulations were working so well that there was ‘no urgent need for legislation.’” Indeed, none of the numerous quota-cutting bills introduced throughout the 1930s passed.

Neither the language of the 1917 act nor the press release that doubled as an executive order indicated how applicants could prove they wouldn’t require public support. Should they show proof of assets?

What kind of assets and in what amounts? Should they provide sworn affidavits from Americans vowing to support them? But who could provide such affidavits, and what financial resources must they possess?

With few guidelines and vast discretion, consular officials could basically do what they wanted.

Top State Department officials made clear what it was they wanted: to reduce immigration as much as possible. They also made clear that consular officials’ careers hinged upon accomplishing that goal. The State Department largely succeeded, primarily by relying upon the public charge clause, historians who have researched its use agree. Once World War II started in 1939, security concerns also were used to deny visas.

About 200,000 refugees from countries under Nazi domination were admitted to the U.S. as immigrants. About 550,000 could have been under existing U.S. quotas. Only once during the 12 years of the Nazi regime, in 1939, was the German quota filled. In all other years, the quota ranged from 7% to 70%.

Reviving the public charge clause

Although immigration laws have changed considerably since the 1930s and 1940s, the existing Immigration and Nationality Act retains a version of the public charge clause. It is as vague as earlier incarnations. Anyone who is likely at any time to become a public charge is inadmissible, but the act doesn’t define what that means.

A related statute suggests “the availability of public benefits” shouldn’t be “an incentive for immigration.” It allows administering agencies to consider factors such as the applicant’s age, health, family status and financial resources.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which is under the Department of Homeland Security, will now start using the new rules to determine admissions to the U.S. and to assess possible status changes for certain immigrants already here.

Those in the country can now be denied permanent legal status if they had used non-cash benefits such as for food and housing in any of 12 months during a 36-month period.

The new regulations specify negative and positive factors immigration officials must consider in deciding who is likely to become a public charge.

Applicants who have enough money to cover “any reasonably foreseeable medical costs” or have a good credit score, for example, are judged favorably. Those who lack private health insurance, a college degree, sufficient English-language skills for the job market or a well-to-do sponsor are assessed negatively.

Of recent applicants from Europe, Canada and Oceania, 27% had two or more negative factors under the new rules, Mark Greenberg of the think tank Migration Policy Institute told The Washington Post.

Of those from Asia, 41% had two or more negative factors. Of those from Mexico and Central America, 60% had two or more negative factors.

In October, the State Department amended its rules for consular officers to use in issuing visas, to be in line with the new public charge interpretation. The Department of Justice has yet to announce its standards for use in deportation and other immigration court proceedings.

The regulations leave the ultimate determination “in the opinion” of the appropriate government official. I see little reason to doubt the result will be fewer and different types of immigrants.

The Trump administration is as likely to succeed in communicating what it wants to lower-level officials as was the State Department in the Nazi era.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of a story that originally ran on August 20, 2019.

[ Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter. ]

Laurel Leff, Associate Professor of Journalism, Northeastern University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.