SECURE

Act Leaves Millions of Workers as Insecure as Ever

|

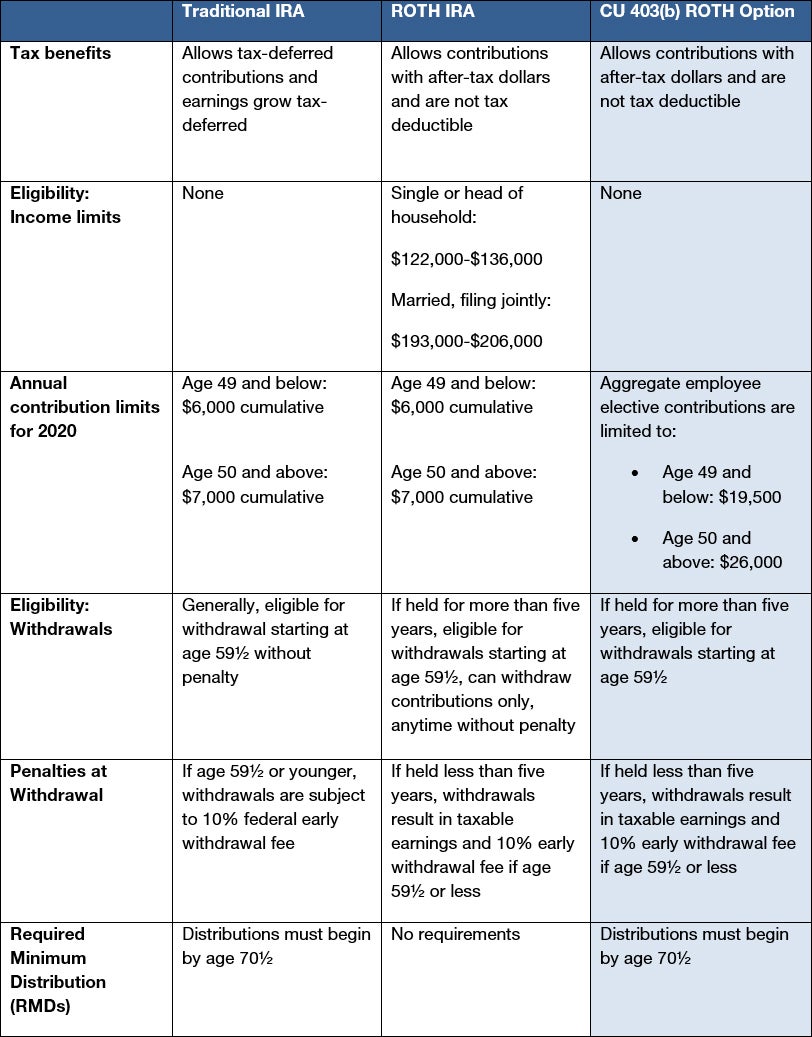

| University of Colorado graphic |

One

big Democratic initiative did manage to become law, pushed through as part of a

late-2019 budget deal. Titled the SECURE Act, it’s the latest effort to reshape

and repair America’s private-sector retirement system.

SECURE

stands for Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement. The bill

doesn’t come close to doing that, partly because the job is so huge.

Despite

extensive use of 401(k)s, IRAs and the like, millions

of employees simply aren’t saving enough to carry them through the Golden

Years. Another 55 million workers, largely

low-income, don’t have workplace

access to any retirement plan; they could easily join the huge

numbers of seniors already managing on little more than Social Security.

Two

provisions of the Act aim at lowering the no-access numbers:

Most promising, the law removes a barrier that’s been keeping small businesses from joining together to form multi-employer plans. Another new rule allows regular part-timers to enroll in 401(k)s if they’ve worked 500 hours for three consecutive years or 1,000 hours in a single year.

Both

changes take effect in 2021. Now for some already in place.

There’s

no longer an age limit

for putting money into traditional IRAs. Contributions formerly had to end at

age 70 ½; now they can continue as long as workers stay on the job. Especially

for those who aren’t saving enough, saving longer gives them a chance to save

more. (The new rule already applies to 401(k) and Roth accounts.)

Annuities

have arrived for 401(k)s. The lion’s share of retirement savings gets invested

in the stock market. That’s not the safest place, as investors have just

re-learned the hard way. Annuities by contrast provide a lifetime income

stream, and the new law “eases

the way for employers to tuck annuities into 401(k) plans.”

In

another major change, the Act ends so-called “stretch” IRAs. President Obama tried

and tried again to get them repealed. Ironically, his wish is now a done

deal signed and delivered by President Trump.

Non-spouse

inheritors were once allowed to keep IRAs active for decades (stretched, in

other words). No longer: with slight exception, the accounts now have to be

cashed out in 10 years.

There

was strong fiscal reason for the repeal. Total tax revenues from those

finally-closed IRAs will reach an estimated $15.7 billion over the next

decade—almost enough to pay for all the bill’s provisions. (It’s a rare

instance of legislation that should ultimately take in nearly as much as it

spends).

In

the end the SECURE Act could have done much more to live up to its name.

The

big shortfall is its lack of any direct impact on workers

without access to retirement plans. The law could have set up universal

payroll-deduction IRAs, an idea endorsed by candidates Obama

and McCain in the 2008 presidential race. Obama’s Administration kept

pushing the idea, once estimating that automatic IRAs might reach around

80 percent of low and middle-income workers.

That’s

what could have happened but didn’t. The law also disappointed in the other

direction, doing something it shouldn’t have. It handed a tax break to those

who need it least.

Most

retirement accounts call for taxable required minimum distributions. These

already had a late start, not kicking in until age 70 1/2. The new law pushes

the starting age back to 72. The later date helps only those who can wait

pretty much forever to tap their nest eggs. It’s also the most expensive of all

the bill’s changes, costing the Treasury more than half of what it stands to

gain from the repeal of “stretch” IRAs.

Summing

up, Democrats deserve some praise for maneuvering the SECURE Act through

Congress. They also deserve some blame for not going further toward improving

our vastly improvable retirement system.

P.S.

The coronavirus pandemic is outside the scope of this article. Going forward, a

bad retirement situation is almost certain to become even worse.

Gerald E. Scorse helped pass the bill requiring basis reporting for capital gains. He writes on taxes.His articles have appeared often in Progressive Charlestown.

© 2020 Gerald E. Scorse