Michael Haedicke, Drake University

|

| Workers in a pork processing plant, 2016. USGAO/Wikipedia |

As of May 1, nearly 5,000 packing plant workers in 19 states had fallen ill, and 20 had died.

Packing plants from Washington state to Iowa to Georgia have temporarily suspended operations, although President Trump has invoked the Defense Production Act in an effort to quickly restart these facilities.

As Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds put it in a press conference, virus outbreaks in packing plants are “very difficult to contain.” But what makes these plants so dangerous?

As a sociologist who has studied food system labor issues, I see two answers.

First, working conditions experienced in meatpacking plants, which are shaped by the pressures of efficient production, contribute to the spread of COVID-19.

Second, this industry has evolved since the mid-20th century in ways that make it hard for workers to advocate for safe conditions even in good times, let alone during a pandemic.

Together, these factors help to explain why U.S. meatpacking plants are so dangerous now – and why this problem will be difficult to solve.

A hard job in good times

The meatpacking industry is an important job source for thousands of people. In 2019 it employed nearly 200,000 people in direct meat processing jobs at wages averaging US$14.13 per hour or $29,400 yearly.

Even in normal conditions, meatpacking plants are risky places to work. The job requires using knives, saws and other cutting tools, as well as operating industrial meat grinders and other heavy machinery.

Traumatic injuries due to workplace accidents are common, and mistakes can have gruesome consequences. Government researchers have also documented chronic injuries, such as repetitive motion strains, among packing plant workers.

The same conditions that lead to these accidents and injuries during normal times also contribute to the spread of coronavirus. To understand this connection, it is first important to know that meatpacking is a volume industry. The higher a plant’s daily throughput – that is, the more animals it turns into meat – the more lucrative it is.

For instance, one Smithfield plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, which shut down indefinitely in April after hundreds of workers tested positive for COVID-19, employed 3,700 people and produced 18 million servings of pork daily.

To maximize efficiency, production takes place on an assembly line – or more accurately, a disassembly line. Workers stand close together and perform simple, repetitive tasks on animal parts as the parts stream by.

Production lines move quickly, with industry averages ranging from 1,000 animals per hour in pork processing to over 8,000 per hour in chicken plants.

In October 2019 the Trump administration eliminated limits on production line speed in pork processing plants, and it has also waived limits for individual chicken processing plants.

|

| Meat processing stations at the JBS Beef Plant in Greeley, Colo., equipped with new sheet-metal partitions, April 23, 2020. As of early May 2020 the plant had recorded more than 200 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 6 employee deaths. Andy Cross via Getty Images |

Employees labor alongside one another, working at a rate that makes it difficult, if not impossible, to practice protective behaviors such as covering sneezes and coughs.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued guidelines to allow meatpacking workers to continue working during the pandemic.

They include spacing workers at least six feet apart and installing barriers between them.

Some plants have adopted these controls, but the pressures of rapid production may well limit their effectiveness.

Unionizing the industry

Understanding why meatpacking workers tolerate these difficult and dangerous conditions requires a look at the industry’s history.

Many people assume that jobs in packing plants have always been as difficult and dangerous as those depicted in journalist Upton Sinclair’s famed 1906 novel “The Jungle.” That book described meatpacking workers in early 20th-century Chicago facing similar conditions to those in the modern industry.

But this assumption conceals an important story. For several decades after World War II, conditions in meatpacking plants steadily improved as a result of pressure from workers themselves.

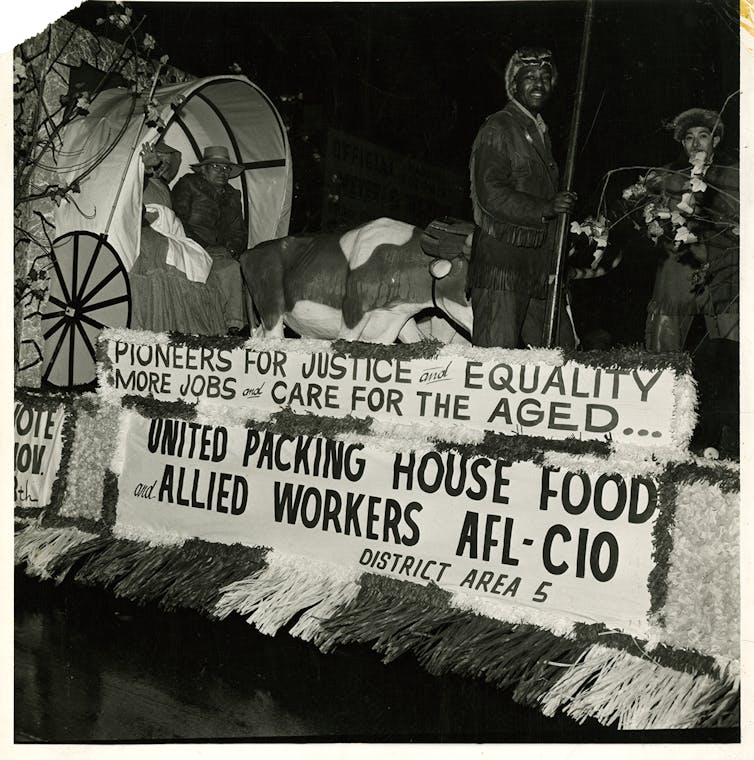

|

| UPWA District Area 5 Members Parade float, circa 1960, Chicago. Source: Chicago Public Library, CC BY-ND |

At the height of its influence, this union secured “master agreements” with the largest firms, such as Armour and Swift, ensuring standard wages and working conditions across the industry.

One source of the UPWA’s influence was its ability to build interracial alliances. Racial antagonism between black and white workers, linked to job discrimination and the use of black workers to break strikes in the early 20th century, had historically undermined union efforts in meatpacking plants.

The union’s logo, which depicted clasped black and white hands, symbolized its ability to bridge these differences.

Its support for the civil rights movement in the 1960s also revealed its commitment to racial equality.

A changing labor force

But by the 1970s, the union was in decline. A key factor was industry leaders’ decision to shift production from cities with a strong union tradition, like Chicago and Kansas City, to small towns scattered across the Great Plains and the southeastern United States.

Rural work forces are more difficult to organize than their urban counterparts for many reasons. Most small towns do not have a history of union activity, and anti-union sentiment is often strong – as shown by the prevalence of right-to-work laws in many rural states.

Moreover, packing plants are often small towns’ only major employers. Workers and municipal authorities alike depend on plants for jobs and tax revenue. This relationship creates enormous pressure to treat meat processing companies with deference.

Additionally, meatpacking consolidated in the late 20th century. Plants grew larger, and a relative handful of firms such as Cargill and Tyson came to dominate processing of beef, poultry and other meats. Consolidation gives these firms greater ability to control working conditions and wages.

Finally, today’s plants often recruit workers from Mexico and Central America, some of whom may lack legal authorization to work in the U.S. They also hire refugees who may be unfamiliar with U.S. labor protections and have few other employment possibilities.

These workers’ precarious legal and economic standing makes it hard for them to challenge employers. Cultural differences, language gaps and racial prejudice can also pose obstacles to collective action.

Workers’ organizations have not disappeared. The United Food and Commercial Workers Union has called on the Trump administration to ensure safety during the pandemic, but it is fighting an uphill battle.

Despite President Trump’s reassurances that closed plants will reopen safely, I expect that the pressures of efficiency and limits on workers’ ability to advocate for themselves will cause infections to persist.

In meatpacking as in other industries, the pandemic has revealed how people who do “essential” work for Americans can be treated as if they are expendable.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Michael Haedicke, Associate Professor of Sociology, Drake University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.