Peter C. Mancall, University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

|

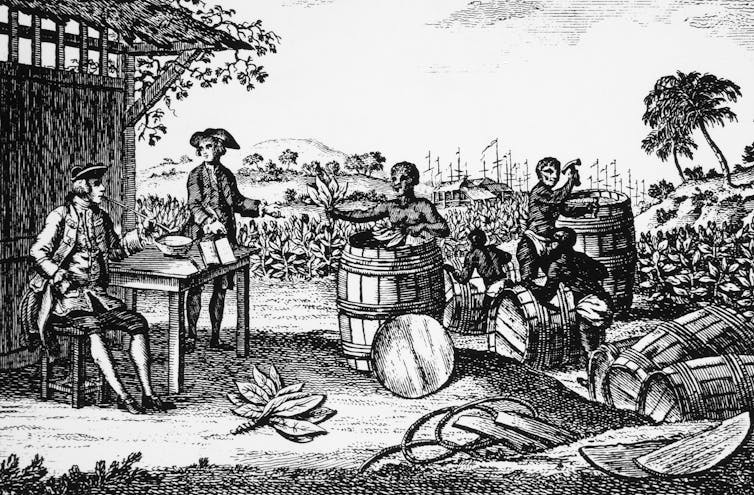

| A 1620 engraving depicts tobacco being prepared for export from Jamestown, Virginia. Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images |

Policymakers are beginning to decide how to reopen the American economy.

Until now, they’ve largely prioritized human health: Restrictions in all but a handful of states remain in effect, and trillions have been committed to help shuttered businesses and those who have been furloughed or laid off.

The right time to start opening up sectors of the economy has been up for debate. But history shows that in the wake of calamities, human life often loses out to economic imperatives.

As a historian of early America who has written about tobacco and the aftermath of an epidemic in New England, I’ve seen similar considerations made in the face of disease outbreaks. And I believe that there are crucial lessons to be drawn from two 17th-century outbreaks during which economic interests of a select few won out over moral concerns.

Tobacco, a love story

During the 16th century, Europeans fell in love with tobacco, an American plant. Many enjoyed the sensations, like increased energy and decreased appetite, that it produced, and most who wrote about it emphasized its medicinal benefits, seeing it as a wonder drug that could cure a variety of human ailments. (Not everyone celebrated the plant; King James I of England warned that it was habit-forming and dangerous.)

By the early 17th century, the English grew increasingly eager to establish a permanent colony in North America after failing to do so in places like Roanoke and Nunavut. They saw their next opportunity along the James River, a tributary of Chesapeake Bay. Following the establishment of Jamestown in 1607, the English soon realized that the region was perfect for cultivating tobacco.

The newcomers, however, didn’t know they had settled in an ideal breeding ground for the bacteria that cause typhoid fever and dysentery.

From 1607 to 1624, approximately 7,300 migrants, most of them young, traveled to Virginia.

By 1625 there were only about 1,200 survivors. A 1622 uprising by local Powhatans and drought-induced shortages of food contributed to the death toll, but most perished from disease. The situation was so dire that some colonists, too weak to produce food, resorted to cannibalism.

Aware that such stories might dissuade possible migrants, the Virginia Company of London circulated a pamphlet that acknowledged the problems but stressed that the future would be brighter.

And so English migrants continued to arrive, recruited from the armies of young people who had moved to London looking for work, only to find scant opportunities. Jobless and desperate, many agreed to become indentured servants, meaning they would work for a planter in Virginia for a set period of time in exchange for passage across the ocean and compensation at the end of the contract.

Tobacco production soared, and despite a drop in the price due to the overproduction of the crop, planters were able to amass substantial wealth.

From servants to slaves

Another disease shaped early America, even though its victims were thousands of miles away. In 1665, the bubonic plague struck London.

The next year, the Great Fire consumed much of the city’s infrastructure. Bills of mortality and other sources reveal that the city’s population may have dropped by as much as 15% to 20% during this period.

The timing of the twinned catastrophes couldn’t have been worse for English planters in Virginia and Maryland. Though demand for tobacco had only grown, many indentured servants from the first wave of recruits had decided to start their own families and farms.

Planters desperately needed labor for their tobacco fields, but English workers who might have otherwise emigrated instead found work at home rebuilding London.

With fewer laborers coming from England, an alternative started to seem increasingly attractive to planters: the slave trade. While the first enslaved Africans had arrived in Virginia in 1619, their numbers grew significantly after the 1660s. In the 1680s, the first anti-slavery movement appeared in the Colonies; by then, planters had come to rely on imported slave labor.

Yet planters didn’t need to prioritize labor-intensive tobacco. For years, Colonial leaders had been trying to convince planters to grow less labor-intensive crops, like corn. But enamored by the allure of profits, they stuck with their cash crop – and welcomed ship after ship of bound laborers. The demand for tobacco outweighed any sort of moral consideration.

Legalized slavery and indentured servitude are no longer familiar parts of the American economy, but economic exploitation persists.

Despite the heated anti-immigration rhetoric that has come from the Oval Office in recent years, the United States continues to rely heavily on immigrant workers, which includes farm workers.

Their importance has become even more apparent during the pandemic, and the government has even declared them “essential.”

After Trump announced his immigration ban on April 20, the executive order exempted farm workers and crop pickers, whose numbers have actually grown under his administration.

So even before states were weighing whether to reopen nonessential businesses, these laborers were on the frontlines, working and sleeping in close proximity, immunocompromised due to chemical exposure, with little access to proper medical care.

And yet rather than reward them for performing this essential work, some in the government are reportedly trying to slash their low wages even further, while giving farm owners a multi-billion-dollar bailout.

Whether it’s a plague or pandemic, the story tends to remain the same, with the quest for profits eventually prevailing over concerns for human health.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Peter C. Mancall, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities, University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.