Don’t stop taking your

meds unless your doctor tells you to

New York University

|

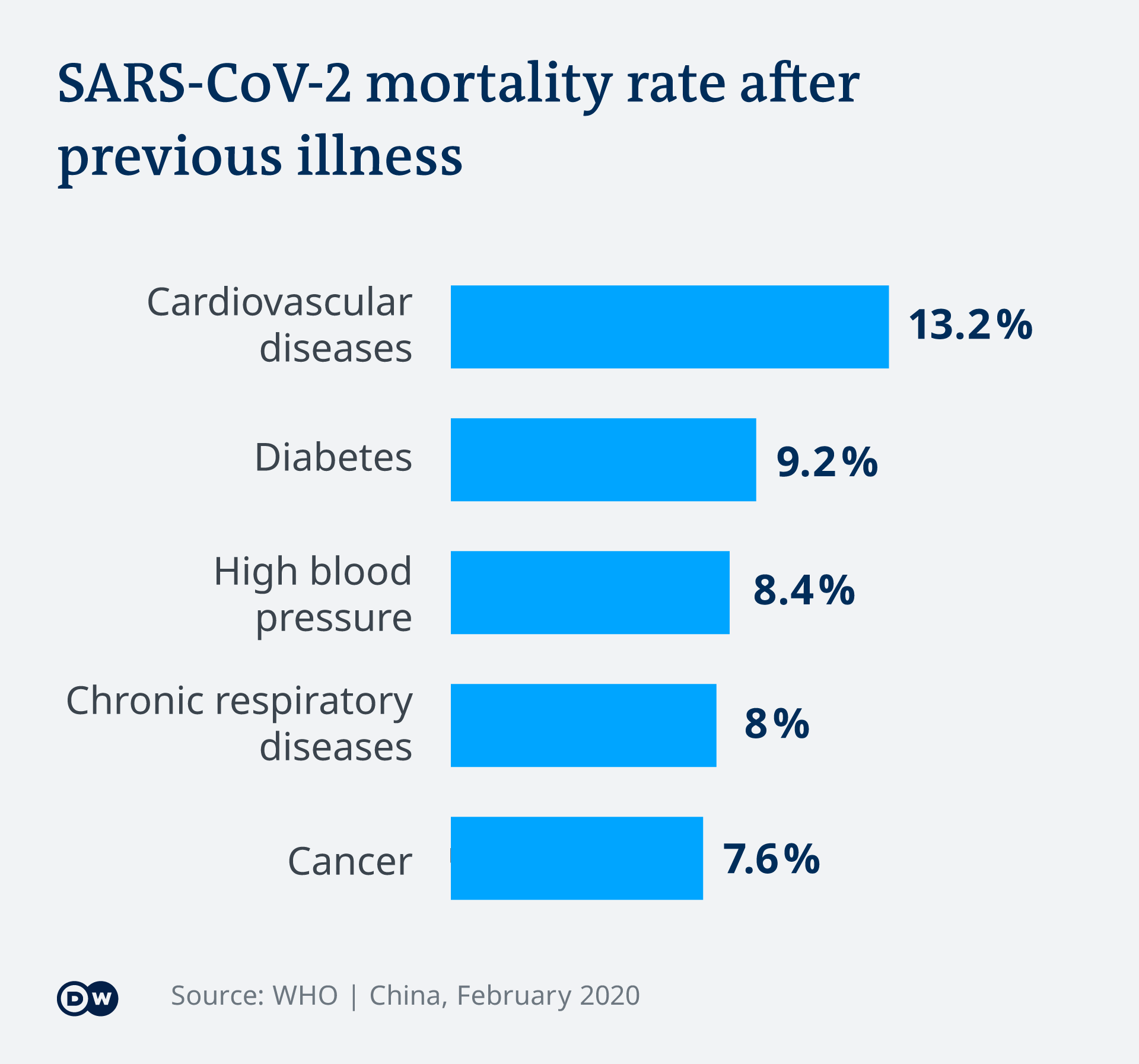

| High blood pressure ADDS to your risk of death from COVID-19. So researchers needed to find out whether blood pressure treatment ALSO added to that risk. SPOILER ALERT: it doesn't. |

Published online May 1 in the New England

Journal of Medicine, the study was launched in response to

a March 17 joint statement issued

by the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the

Heart Failure Society of America.

It urgently called for research to answer a question raised by past studies: do high blood pressure (antihypertensive) medications worsen COVID-19 patient outcomes?

It urgently called for research to answer a question raised by past studies: do high blood pressure (antihypertensive) medications worsen COVID-19 patient outcomes?

Led by researchers

from NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the study found no links between

treatment with four drug classes—angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)

inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, or calcium

channel blockers—and increased likelihood of a positive test for COVID-19.

Further, the study

found no substantial increase in risk for more severe illness (intensive care,

use of a ventilator, or death) with any of the treatments in patients with the

pandemic virus.

“With nearly half of American adults having high blood pressure, and heart disease patients more vulnerable to COVID-19, understanding the relationship between these commonly used medications and COVID-19 was a critical public health concern,” says lead investigator Harmony R. Reynolds, MD, associate director of the Cardiovascular Clinical Research Center at NYU Langone Health.

“Our findings should reassure the medical community and patients about the continued use of these commonly prescribed medications, which prevent potentially severe heart events in their own right.”

For the study, the researchers identified patients in the NYU Langone electronic health record with COVID-19 test results. For each identified patient with COVID-19 test results, the team discretely extracted medical history needed for the analysis, which compared treated and untreated patients.

“Before our study, there were no experimental or clinical data demonstrating the consequences of using these medications one way or the other in people at risk for COVID-19,” says senior study author Judith S. Hochman, MD, the Harold Snyder Family Professor of Cardiology in the Department of Medicine and senior associate dean for clinical sciences at NYU Langone.

“In terms of next steps, our plan is to use similar approaches to investigate other medications and their relationship to COVID-19 illness.”

Cause for Concern

The study revolves

around medications that act on the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone hormonal

system, which influences blood pressure. Central to this system is the

signaling protein angiotensin II, levels of which are controlled by ACE, say

the authors.

Angiotensin II narrows blood vessels to increase blood pressure, and the study medications counter that, either by blocking ACE-induced increases in angiotensin II, or the ability of ACE to interact with its receptor signaling partners on cells.

Angiotensin II narrows blood vessels to increase blood pressure, and the study medications counter that, either by blocking ACE-induced increases in angiotensin II, or the ability of ACE to interact with its receptor signaling partners on cells.

According to the

researchers, one version of ACE—ACE2—is present in the outer membrane of lung

cells. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the

current pandemic virus, has been shown to connect to ACE2 on lung cells, a

first step toward viral infection. This led to concern in the field that ACE

inhibitors and ARBs might increase or worsen COVID-19 infection.

Past studies in animal models had suggested that ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 production in other organs, but how they related to ACE2 levels in the lungs was not known.

Past studies in animal models had suggested that ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 production in other organs, but how they related to ACE2 levels in the lungs was not known.

On the other hand, ACE inhibitors and ARBs had been shown elsewhere to reduce lung injury in certain viral pneumonias, creating speculation that they might be helpful. The new study was designed to address these contradictions.

Along with Dr. Reynolds

and Dr. Hochman, authors of the study from NYU Langone were Andrea B. Troxel, ScD, director of the Division of Biostatistics; Samrachana Adhikari, PhD; Claudia Pulgarin,

MA, MS; Eduardo Iturrate, MD; Stephen B. Johnson, PhD; Anais Hausvater,

MD; Jonathan Newman, MD, MPH; Jeffrey S. Berger, MD; Sripal Bangalore, MD; Stuart D. Katz, MD; Glenn I. Fishman, MD; Dennis Kunichoff; Yu Chen, PhD, MPH; and Olugbenga G. Ogedegbe, MD, MPH.