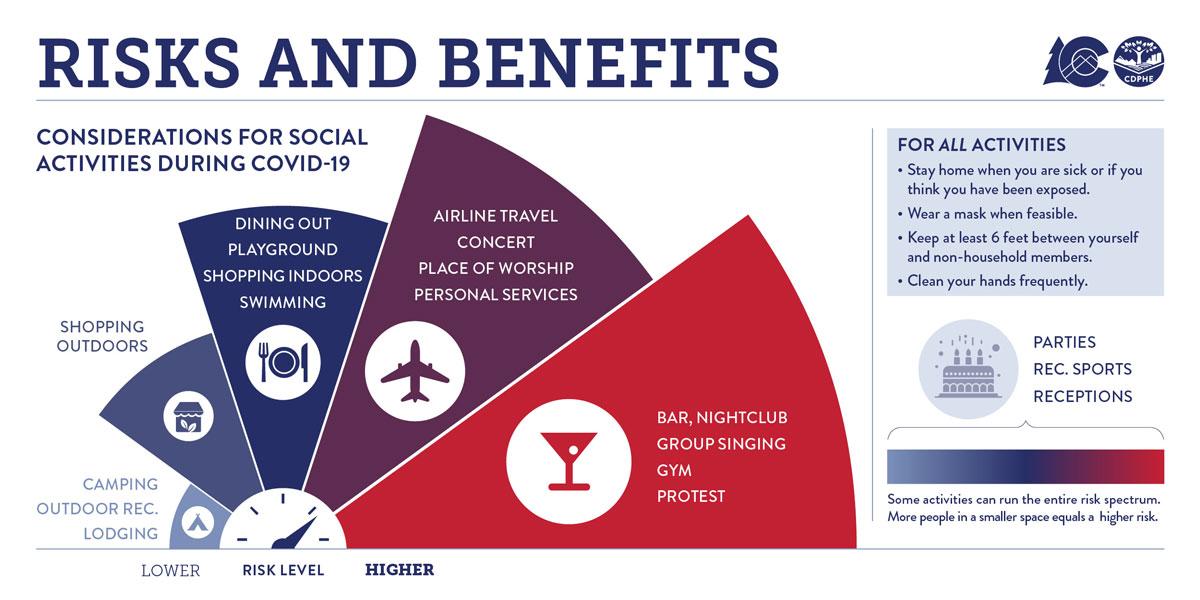

MIT scientists look at risk and reward for opening certain types of businesses during the pandemic

Massachusetts

Institute of Technology

Banks

and bookstores. Gyms and juice bars. Dental offices and department stores. The

Covid-19 crisis has shuttered some kinds of businesses, while others have

stayed open.

Banks

and bookstores. Gyms and juice bars. Dental offices and department stores. The

Covid-19 crisis has shuttered some kinds of businesses, while others have

stayed open. But which places represent the best and worst tradeoffs, in terms of the economic benefits and health risks?

A

new study by MIT researchers uses a variety of data on consumer and business

activity to tackle that question, measuring 26 types of businesses by both

their usefulness and risk.

Vital forms of commerce that are relatively uncrowded fare the best in the study; less significant types of businesses that generate crowds perform worse. The results can help inform the policy decisions of government officials during the ongoing pandemic.

Vital forms of commerce that are relatively uncrowded fare the best in the study; less significant types of businesses that generate crowds perform worse. The results can help inform the policy decisions of government officials during the ongoing pandemic.

As it happens, banks perform the best in the study, being economically significant and relatively uncrowded.

"Banks

have an outsize economic impact and tend to be bigger spaces that people visit

only once in a while," says Seth G. Benzell, a postdoc at the MIT

Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) and co-author of a paper published

Wednesday that outlines the study. Indeed, in the study, banks rank first in

economic importance, out of the 26 business types, but just 14th in risk.

"Banks

have an outsize economic impact and tend to be bigger spaces that people visit

only once in a while," says Seth G. Benzell, a postdoc at the MIT

Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) and co-author of a paper published

Wednesday that outlines the study. Indeed, in the study, banks rank first in

economic importance, out of the 26 business types, but just 14th in risk.

By

contrast, other business types create much more crowding while having far less

economic importance. These include liquor and tobacco stores; sporting goods

stores; cafes, juice bars, and dessert parlors; and gyms.

All of those are in the bottom half of the study's rankings of economic importance. At the same time, cafes, juice bars, and dessert parlors, taken together, rank third-highest out of the 26 business types in risk, while gyms are the fifth-riskiest according to the study's metrics -- which include cellphone location data revealing how crowded U.S. businesses get.

All of those are in the bottom half of the study's rankings of economic importance. At the same time, cafes, juice bars, and dessert parlors, taken together, rank third-highest out of the 26 business types in risk, while gyms are the fifth-riskiest according to the study's metrics -- which include cellphone location data revealing how crowded U.S. businesses get.

"Policymakers

have not been making clear explanations about how they are coming to their

decisions," says Avinash Collis PhD '20, an MIT-trained economist and

co-author of the new paper. "That's why we wanted to provide a more

data-driven policy guide."

And

if the Covid-19 pandemic worsens again, the research can apply to shuttering businesses

again.

"This

is not only about which locations should reopen first," says Christos

Nicolaides PhD '14, a digital fellow at IDE and study co-author. "You can

also look at it from the perspective of which locations should close first, in

another future wave of Covid-19."

The

paper, "Rationing Social Contact During the COVID-19 Pandemic:

Transmission Risk and Social Benefits of U.S. Location," appears in Proceedings

of the National Academy of Science, with Benzell, Collis, and Nicolaides as

the authors.

Cumulative

risk

To

conduct the study, the team examined anonymized location data from 47 million

cellphones, from January 2019 through March 2020. The data included visits to 6

million distinct business venues in the U.S. The 26 types of businesses in the

study accounted for 57 percent of those visits, meaning the study covers a

broad swath of the economy.

By

examining the location data over an extended time period, the scholars were

able to determine what the typical crowding level is for all business types in

the study.

The

study also used payroll, revenue, and employment data from U.S. Census Bureau

to rate the centrality of different industries to the economy. Businesses in

the study represented 1.43 million firms, 32 million employees, $1.1 trillion

in payroll, and $5.6 trillion in revenues. The researchers also added a survey

of 1,099 people people to gauge public preferences about different types of

business.

A

key to the researchers' approach is recognizing that during the pandemic, many

consumers are trying to limit trips that generate interaction with strangers,

while still needing to get essential and useful transactions done.

As

Benzell notes, "The idea was, how can we think about rationing social

contacts in a way that gives us the most bang for our buck, in terms of

meetings, while keeping the risk of Covid transmission as low as

possible?"

The

study also rates risk on the basis of aggregate public exposure, per business

type. On an individual basis, spending a couple of hours in a movie theater

with strangers might seem quite risky.

But in February 2020, movie theaters had about 17.6 million consumer visits in the U.S., whereas sit-down restaurants had almost 900 million visits in the same month. As a business category, sit-down restaurants would likely generate much more total transmission of Covid-19.

But in February 2020, movie theaters had about 17.6 million consumer visits in the U.S., whereas sit-down restaurants had almost 900 million visits in the same month. As a business category, sit-down restaurants would likely generate much more total transmission of Covid-19.

"It's

not danger per visit, but it's a cumulative danger," Nicolaides explains.

"If you look at movie theaters, they seem dangerous, but not that many

people go to the movies every day ... and restaurants are a good

counter-example."

Outlier:

Liquor stores staying open

In

many cases, the researchers say, policymakers have made reasonable decisions

about which types of businesses should be open and closed. But there are

exceptions to this. Take liquor stores, which have been deemed an

"essential" business in many U.S. states.

"What really jumps out at us is liquor and tobacco stores," Benzell says. "Most states have allowed liquor stores to remain open. This is a bit of a bad call from our perspective, because liquor stores don't create a lot of social value. If you ask people which stores they want to be open, liquor stores are near the bottom of that list. They don't have that many receipts or employees, and they tend to be these small, crowded places where people are up against each other trying to navigate."

In the study, liquor stores rate 20th out of the 26 business types in economic importance, but 12th highest in risk.

By

contrast, the researchers are more bullish about the public health dynamics of

college and universities, which they rank 8th out of the 26 business types in

economic importance, but just 17th in terms of risk. If campus living

arrangements could be made more safe, the researchers think, the other parts of

university life could offer relatively reasonable conditions.

"Colleges

and universities actually have the potential to offer pretty good social

contact tradeoffs," Benzell says. "They tend to be places with big

campuses, they tend to be [composed of] consistently the same group of young

people, visiting the same places.

When people are worried about colleges and universities, they're mostly worried about dormitories and parties, people getting infected that way, and that's fair enough. But [for] research and teaching, these are big spaces, with pretty modest groups of people that produce a lot of economic and social value."

When people are worried about colleges and universities, they're mostly worried about dormitories and parties, people getting infected that way, and that's fair enough. But [for] research and teaching, these are big spaces, with pretty modest groups of people that produce a lot of economic and social value."

The

scholars note that the study contains national ratings, and acknowledge that

there might be some regional variation in effect as well.

"If

a local government would like to apply this paper [to their policies], it may

be a better idea to put in their own data to make decisions," says

Nicolaides.

That said, the study did not indicate significantly different results for urban and rural settings, something the researchers evaluated.

That said, the study did not indicate significantly different results for urban and rural settings, something the researchers evaluated.

To

be sure, some businesses are adapting to the pandemic by using new protocols or

safety measures, such as limited customers in hair salons or safety partitions

at supermarket checkout counters.

Studying business venues with such safety measures in place would also be valuable, the scholars note.

Studying business venues with such safety measures in place would also be valuable, the scholars note.

"Moving

forward, an interesting exercise would be to see how dangerous these locations

are once you implement these mitigation strategies." Collis says.

"Those are all interesting open questions, seeing which business adapt.

And some of these adaptations will probably be temporary changes, but other

business practices may stick in the Covid age."

Research

support was provided by MIT's Initiative on the Digital Economy.