Rhode

Island’s Dark History

By Phil Eil

On

June 21st, 1924, the Ku Klux Klan held a rally in Foster, Rhode Island.

On

June 21st, 1924, the Ku Klux Klan held a rally in Foster, Rhode Island. Thousands of people attended from across New England, some traveling in caravans of cars from Newport and New Haven.

The day featured speakers from Pennsylvania and Connecticut and female lecturers who specifically addressed the women in attendance.

An account published by the Rhode Island Historical Society notes that “at the conclusion of the field day and clam chowder dinner, several hundred [attendees] were initiated under a blazing cross.”

Longtime

Rhode Islanders, including myself, like to talk about the ways Rhode Island

feels separate from the rest of the United States. We’re a tiny place in an

enormous country. (Statistically, our land mass is 0.03 percent of the entire

nation, which basically rounds down to zero.)

We have a proud legacy of homegrown weirdos, outlaws, artists, and free-thinkers, starting with our iconoclastic state founder, Roger Williams. And we have our own distinct rituals (WaterFire) and cuisine (Del’s lemonade, New York System wieners, coffee milk). Rhode Island is delightfully different, and we love it for that reason.

We have a proud legacy of homegrown weirdos, outlaws, artists, and free-thinkers, starting with our iconoclastic state founder, Roger Williams. And we have our own distinct rituals (WaterFire) and cuisine (Del’s lemonade, New York System wieners, coffee milk). Rhode Island is delightfully different, and we love it for that reason.

But,

in some of the most important ways, Rhode Island is a deeply American place —

which is to say, a place haunted by hatred, oppression, and racial injustice.

And as protests sweep across the nation following the murders of George Floyd

and Breonna Taylor, and countless other racially-motivated injustices, it’s

important to remember our less flattering history.

If you’re an Ocean State resident feeling powerless and disturbed by recent events, here is at least one tangible thing you can do: educate yourself about the nightmares that took place in our backyard.

If you’re an Ocean State resident feeling powerless and disturbed by recent events, here is at least one tangible thing you can do: educate yourself about the nightmares that took place in our backyard.

Rhode

Island, like the rest of the United States, was brutally racist from its

origins. In the 18th century, the state emerged as a hub for the slave trade, launching hundreds of voyages

that, by some estimates, carried as many as 100,000 Africans in

bondage back across the Atlantic.

Many of those captives died on the journey. In Providence, Brown University’s iconic University Hall was constructed with the use of enslaved workers.

In Newport, as a historian on a podcast recently reminded listeners, “the duties collected on the purchase and sale of enslaved people in Rhode Island were used to pave the streets.”

Bristol, home of the nation’s oldest of Fourt of July parade, is also the home of the nation’s most prolific slave-trading family: the DeWolfs, for whom a street and tavern are still named.

Many of those captives died on the journey. In Providence, Brown University’s iconic University Hall was constructed with the use of enslaved workers.

In Newport, as a historian on a podcast recently reminded listeners, “the duties collected on the purchase and sale of enslaved people in Rhode Island were used to pave the streets.”

Bristol, home of the nation’s oldest of Fourt of July parade, is also the home of the nation’s most prolific slave-trading family: the DeWolfs, for whom a street and tavern are still named.

Although

the slave trade eventually dwindled, racism and discrimination showed in other

ways. In 1822, men of African heritage were barred from voting in RI. In the 1820s and 1830s,

Providence was rocked by racial unrest during which armed mobs roamed the

streets and predominantly black neighborhoods were vandalized.

The cause for one riot, according to a New England Historical Society account? “Apparently a black man had refused to step aside for a white man on the sidewalk.”

The cause for one riot, according to a New England Historical Society account? “Apparently a black man had refused to step aside for a white man on the sidewalk.”

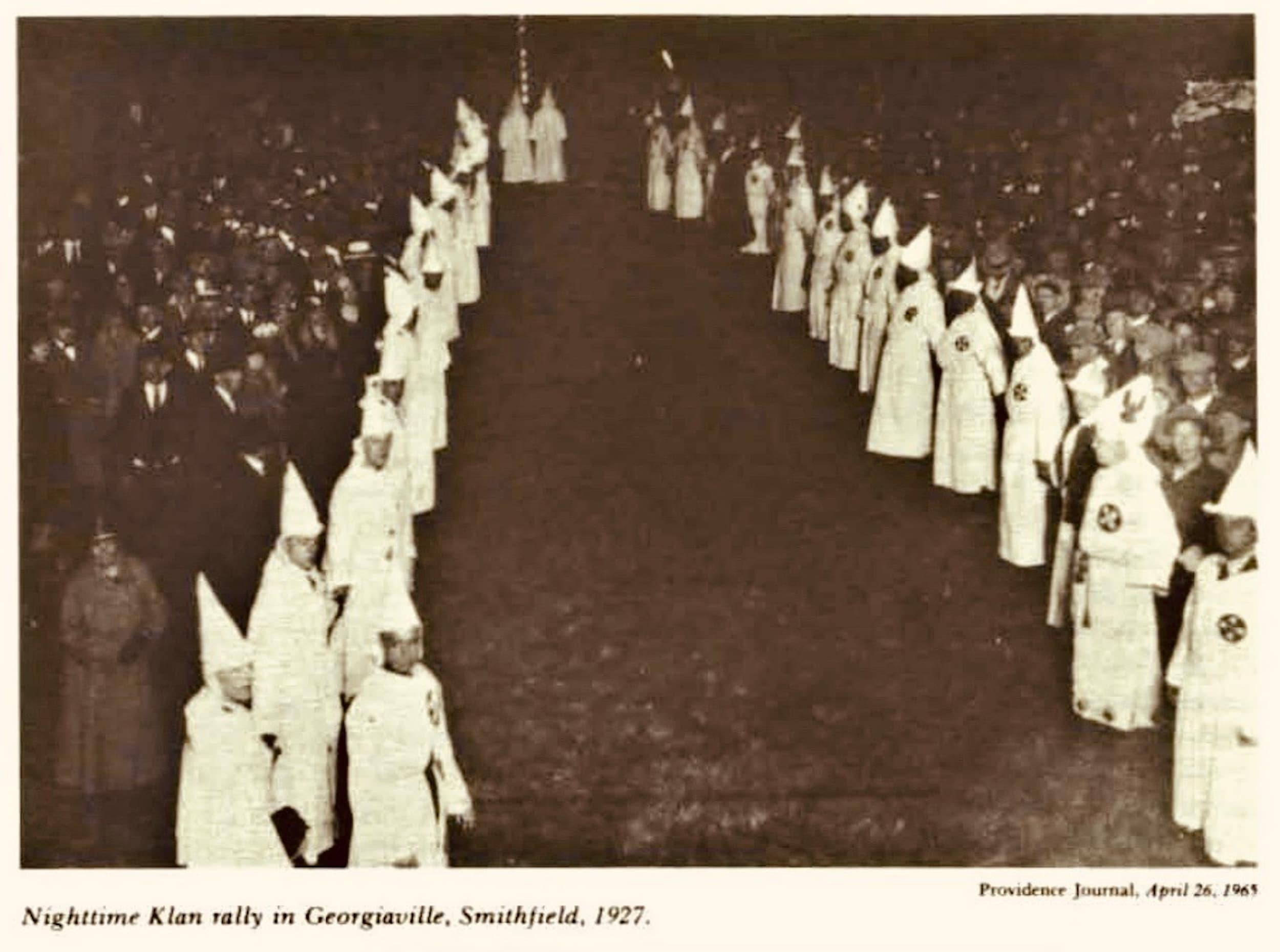

In

1924, Foster played host to a second massive Ku Klux Klan

rally, this one so large — 8,000 participants, hailing from at least six states

— that it was covered in the New York Times, which

noted that, “there were not efforts on the part of public authorities or others

to interfere.”

This was one of many Klan-related events during the 1920s, including an outdoor rally in Greenville, an oyster supper featuring a “100% Klan band” in Coventry, and a public dinner-dance held at the famed Rhodes on the Pawtuxet in Cranston (the venue for my senior prom in 2003). At one point, a notice for a local Klan meeting appeared on the front page of the Woonsocket Call.

This was one of many Klan-related events during the 1920s, including an outdoor rally in Greenville, an oyster supper featuring a “100% Klan band” in Coventry, and a public dinner-dance held at the famed Rhodes on the Pawtuxet in Cranston (the venue for my senior prom in 2003). At one point, a notice for a local Klan meeting appeared on the front page of the Woonsocket Call.

Even

into the mid and late 20th century, there were overt cases of racial hatred and

discrimination. In 1959, coverage of the Newport Jazz Festival mentioned

hotels’ and hostels’ discrimination against black visitors.

In a recent presentation, local businessman and historical consultant Keith Stokes recalled, “I grew up in Newport in the 1970s and thought constantly that at least I didn’t live in rural Mississippi, but things were just as bad in Rhode Island.”

In 2000, an off-duty black Providence police officer was shot and killed by two of his fellow officers, which prompted the local NAACP to release a statement asking, “Did Officer Young have the opportunity to identify himself or is there a shoot- first, ask-questions-later policy?”

In a recent presentation, local businessman and historical consultant Keith Stokes recalled, “I grew up in Newport in the 1970s and thought constantly that at least I didn’t live in rural Mississippi, but things were just as bad in Rhode Island.”

In 2000, an off-duty black Providence police officer was shot and killed by two of his fellow officers, which prompted the local NAACP to release a statement asking, “Did Officer Young have the opportunity to identify himself or is there a shoot- first, ask-questions-later policy?”

Today,

it would be comforting to think that we have evolved, or that the worst

American racism and discrimination happens elsewhere. But glaring — and tragic

— racial disparities remain in household income, high-school dropout rates, incarceration rates,

and access to health care, among other key quality-of-life metrics.

For a recent example, look at the way that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected communities of color in the Ocean State.

For a recent example, look at the way that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected communities of color in the Ocean State.

In

response to recent unrest, Governor Gina Raimondo has said that protesters’ “fear and outrage needs to

be heard, and we need to address it.” But not all work falls to our elected

leaders. Change can often flow from a reassessment of our shared history and

the stories we tell about ourselves.

You can’t fully address a problem if you suffer from what one local historian recently called “historical amnesia.” Unfortunately, that amnesia was on full – and glaring – display when House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello stumbled through a discussion of Rhode Island’s ties to the slave trade.

You can’t fully address a problem if you suffer from what one local historian recently called “historical amnesia.” Unfortunately, that amnesia was on full – and glaring – display when House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello stumbled through a discussion of Rhode Island’s ties to the slave trade.

The good news is that this condition is not terminal.

With commitment, curiosity, and a stomach for introspection and difficult conversations, you can begin to understand what it means — what it really means — to be a Rhode Islander.

You can visit Brown University’s slavery memorial, or take a walking tour of Providence focusing on Black history, or make a point of visiting each of the state’s slave history medallions.

You can read books like Charles Rappleye’s award-winning Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution or Christy Clark-Pujara’s Dark Work: The Business of Slavery In Rhode Island.

You can watch films like Traces of the Trade: a Story from the Deep North, during which the filmmaker and narrator, a descendant of the Dewolf family, describes Rhode Island as “the state most complicit in the American slave trade.”

You can Follow the Center for Reconciliation or Brown’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice on social media, and attend their programs and exhibitions. And, generally speaking, you can — and should — be skeptical of any presentation of local history that ignores, or whitewashes, the atrocities that happened here.

Rhode

Island is an exceptional place in many ways. But when it comes to America’s

shared history of racism, we’re all too typical.

Phil Eil is a freelance journalist

based in Providence, his hometown. Follow him on Twitter: @phileil.

Can we please ask a favor?

Funding

for UpRiseRI reporting relies entirely on the generosity of readers like you. Our

independence is how we are able to write stories that hold RI state and local

government officials accountable. All of our stories are free and available to

everyone right here at UpriseRI.com. But your support is essential to keeping

Steve on the beat, covering the costs of reporting many stories in a single

day. If you are able to, please support Uprise RI. Every contribution, big or

small is so valuable to us. You provide the motivation and financial support to

keep doing what we do. Thank you.