How science, data can inform personal choices during the pandemic

Brown University

Lately, Emily Oster’s inbox

has been flooded with questions from parents who are worried about the risk of

COVID-19 sickening themselves and their children.

Lately, Emily Oster’s inbox

has been flooded with questions from parents who are worried about the risk of

COVID-19 sickening themselves and their children.

Oster, a professor of economics at

Brown University, has earned a national reputation for the data-driven

pregnancy and parenting advice she shared in the bestselling books “Expecting

Better” and “Cribsheet.”

Thousands of parents also subscribe to her e-newsletter ParentData, where she has lately drawn from scientific studies and datasets to weigh in on whether it’s safe for children and grandparents to interact, whether pregnancy exacerbates a woman’s chances of contracting COVID-19, and how daycare services can resume.

Thousands of parents also subscribe to her e-newsletter ParentData, where she has lately drawn from scientific studies and datasets to weigh in on whether it’s safe for children and grandparents to interact, whether pregnancy exacerbates a woman’s chances of contracting COVID-19, and how daycare services can resume.

But Oster — driven to make a

positive impact through her research, like so many scholars in the Brown

community — wanted to do more to help members of the public, whether parents or

not, understand the basic principles of the virus, including how it spreads and

what people can do to protect themselves and their loved ones.

So she partnered with Galit Alter, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, to create the website COVID Explained, a no-nonsense guide to understanding, navigating and protecting oneself from COVID-19.

So she partnered with Galit Alter, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, to create the website COVID Explained, a no-nonsense guide to understanding, navigating and protecting oneself from COVID-19.

Together with students, faculty and

staff at Brown, Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other

universities, Oster and Alter have built a practical resource aimed at anyone

and everyone, in the U.S. and beyond.

Following the website’s launch,

Oster — who is also deep in scenario-planning for Brown’s next academic year,

as co-chair of the University’s Healthy Fall 2020 Task Force — answered

questions about COVID Explained.

I’ve been writing a bunch about

COVID-19 in my newsletter from the perspective of parenting and the Brown

community. A friend of mine who reads the newsletter called and said, “I feel

like there are some things missing from the broader conversation about COVID.”

In particular, she said, there are a lot of scientists who are making notable progress on treatment and testing, but their voices are not being amplified in policy discussions.

In particular, she said, there are a lot of scientists who are making notable progress on treatment and testing, but their voices are not being amplified in policy discussions.

That could be because people are

having a hard time understanding some basic facts about the virus. I think

earlier this spring, there were lots of good public resources — graphs

that demonstrated the trajectory of the virus and explained the concept of “flattening

the curve.”

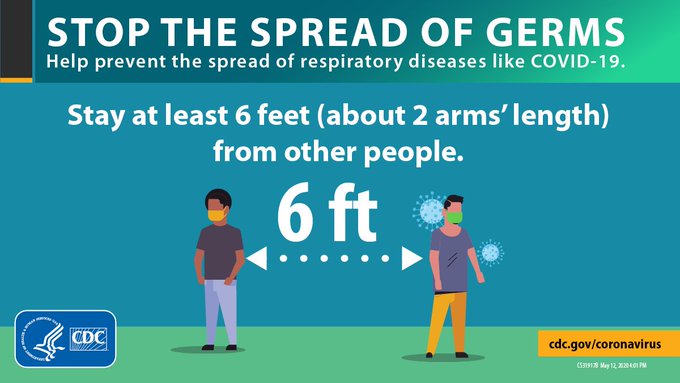

But we didn’t follow up with helpful graphics and information that addressed common questions like: How does the virus spread? What can you do to prevent getting sick?

But we didn’t follow up with helpful graphics and information that addressed common questions like: How does the virus spread? What can you do to prevent getting sick?

As a result, I think a lot of people

came away thinking, if someone who is sick with COVID touches a salad box at

Whole Foods, and then I touch it 3 hours later, I’m going to get sick. And if

you’re coming in with that understanding, you don’t know that the virus can’t

“seep in” to your skin, and then you maybe don’t understand the point of

washing your hands after you get home from Whole Foods.

I wanted people to know the basic facts: The virus cannot live that long on a salad box, and even if it could, you can still prevent yourself from getting sick by washing your hands, because that prevents the virus from spreading to your nose and mouth.

I wanted people to know the basic facts: The virus cannot live that long on a salad box, and even if it could, you can still prevent yourself from getting sick by washing your hands, because that prevents the virus from spreading to your nose and mouth.

Q: What does the content creation

process for COVID Explained look like? Who else is involved?

Right now, there’s a large

interdisciplinary team working to put all this together. Often,

I will say, okay, we need to put together a piece explaining herd immunity.

What percentage of the population needs to be immune before we achieve herd

immunity? How do we get there?

We start by digging into the

science. I ask someone with expertise in this field, often a Ph.D. student or a

postdoctoral researcher, to draft a piece drawing on several studies. Then I

will take a pass at the piece and frame it to be more understandable to a lay

audience, while keeping it grounded in hard science.

We also have several extraordinary Brown undergraduate students who are reading, editing and fact-checking. Some of them are using these long-form explainer pieces to generate more questions that we can answer.

We also have several extraordinary Brown undergraduate students who are reading, editing and fact-checking. Some of them are using these long-form explainer pieces to generate more questions that we can answer.

A lot of people are struggling

with how or whether to get haircuts, eat at restaurants or go to the beach.

Understanding how the virus spreads is the key to making the best choices about

all of these specific things.

EMILY

OSTER Professor of Economics

Q: What can people learn from the

website that they wouldn’t necessarily get from news coverage?

I think we can help give people context. When you read or see coverage on, say, new facts about the virus, new statistics or a new study related to the virus, those new developments tend to be covered largely in isolation.

If you don’t have the background knowledge to put this latest development in context, it’s difficult to process the information in a way that is helpful. We are aiming to fill in the gaps.

I think a lot of people also feel

confused when they hear reports that conflict with one another. One day they

hear a vaccine is in development and the trials are looking promising, and the

next day they hear we might not have a vaccine until 2027.

We’re stepping back and saying: Here’s how vaccine development works, and here’s what experiments are taking place right now. Having that knowledge helps people process and consider new pieces of news without wildly overreacting one way or the other.

We’re stepping back and saying: Here’s how vaccine development works, and here’s what experiments are taking place right now. Having that knowledge helps people process and consider new pieces of news without wildly overreacting one way or the other.

Q: COVID Explained gives an overview

of the risk associated with certain activities, such as visiting grandparents

and putting kids in daycare, without always providing explicit advice. How can

people evaluate which risks are worth taking right now?

I think earlier on in the pandemic,

there was a general feeling of, “Don’t you want to do the safest possible

thing?” And the safest thing, as most people understood it, was to never leave

home. But I think people have realized over time that, even if only for mental

health reasons, that may not be the safest thing.

Society has adapted to take certain

risks. Every time you drive your car, for example, you’re taking a risk — you

could injure yourself or even die, or you could injure someone else. But we

calculate that driving is a risk worth taking.

We may need to do the same thing with COVID-19. We may need to switch our thinking a little bit to, “What is the safest way to do this activity or that activity?” People may disagree about whether it’s right to have a barbecue with family members, for example. But we all agree that, were someone to have a family barbecue, we would want to make sure they were doing it in the safest way possible.

We may need to do the same thing with COVID-19. We may need to switch our thinking a little bit to, “What is the safest way to do this activity or that activity?” People may disagree about whether it’s right to have a barbecue with family members, for example. But we all agree that, were someone to have a family barbecue, we would want to make sure they were doing it in the safest way possible.

Q: What is the most important thing

you want readers to understand about the virus?

I think the big, overarching

takeaway is that if you understand how the virus spreads, you can make better

choices. We launched this website when everything was closed, but now that

Rhode Island and other states are beginning to open back up, I think

understanding the basic information is even more important.

A lot of people are struggling with how or whether to get haircuts, eat at restaurants or go to the beach. Understanding how the virus spreads is the key to making the best choices about all of these specific things.

A lot of people are struggling with how or whether to get haircuts, eat at restaurants or go to the beach. Understanding how the virus spreads is the key to making the best choices about all of these specific things.